Louis Dumont’s contrast between homo hierarchicus as representative of traditional non-Western societies and homo aequalis as descriptive of the human person in Western thought is instructive as also representing a shift in emphasis from the pre-modern Ancien Régime to modern (and ultramodern) individualism. We might link this shift to the broader movement in scientific and intellectual circles towards a new method of inquiry. Consider, for instance, the Novum Organum of Francis Bacon, which proposed a “new ordering of knowledge.” As David H. Hopper has written, “Bacon’s statement of the inductive method nonetheless provided a major, ongoing stimulus to scientific inquiry. An equally significant contribution to the intellectual mindset of the modern world lay in his searching critique of inherited knowledge, a contribution that underlay, as supposition, his central maxim about the temporal nature of truth.” This “central maxim” was that “rightly truth is called the daughter of time, not of authority.”

In this way the hierarchy of authority was undermined. Human beings were no longer to consider themselves as humbly “standing upon the shoulders of giants,” but rather as recipients of a temporal legacy oriented toward progress and ever-greater understanding. The world had, in Kant’s language, “come of age.”

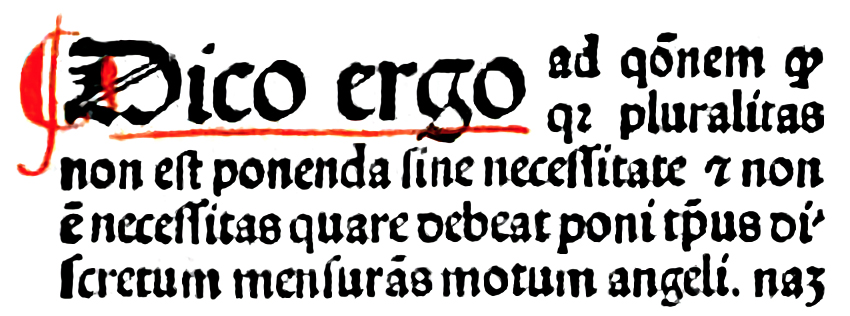

These kinds of historical typologies can be helpful, but the reality is that things are far messier than can be neatly captured by a simple equation of hierarchy with pre-modernity and equality with modernity. We might look, for instance, at the medieval legacies of figures like Scotus and Ockham for roots of modern ideas of science and human society. Indeed, what amounts to the basic insight of a subsidiarity “from below” model is ancient as well. The inductive model of subsidiarity, which has come to be characteristic of modern approaches to the doctrine, can be understood as an application of Ockham’s razor to social philosophy. The idea that “it is futile to do with more things that which can be done with fewer” (frustra fit per plura quod potest fieri per pauciora) has a rather long philosophical pedigree, and can be traced back at least to Aristotle (who also held some rather strongly hierarchical ontological views). A variation focused on proximity and abstraction captures the idea of subsidiarity “from below” quite well: It is vain to seek solutions from sources more distant than is necessary. The basic locus of responsibility is therefore placed with the individual human person, with responsibilities emanating outward and upward.

Luther’s teaching about the universal priesthood of believers is a good place to look for how these interrelated dynamics work out in a particular setting. We can see something like the egalitarian impulse (certainly mixed with various elements of hierarchicalism) in Luther’s view. As the Reformation progressed in various places, this egalitarian emphasis was worked out in different ways. In France, for instance, we see the Reformed churches confessed “that all true pastors, wherever they may be, have the same authority and equal power under one head, one only sovereign and universal bishop, Jesus Christ; and that consequently no Church shall claim any authority or dominion over any other” (Gallican Confession, art. 30). Glenn Sunshine calls this “the most fundamental principle of French Reformed polity” and the hallmark of Presbyterianism.

This does not exclude hierarchy of every kind, but in terms of church politics, at least, the hierarchy becomes one of procedure and function rather than ontological authority. Thus the Synod of Emden in 1571, in its first article, held that no church shall have authority (“lord it over”) another church, no pastor over another, no elder over another, and no deacon over another. The synod would restrict itself to addressing matters that could not be solved at the lower levels of congregation and classis.

In this way a conception of subsidiarity “from below” is focused on the location of sovereignty from the “bottom up” rather than on the delegation of authority from the “top down.” We see these variegated approaches to subsidiarity and sovereignty work out in diverse ways in later centuries. It is with these different lenses of subsidiarity “from above” and “from below” that we can better understand the developments of the Roman Catholic principle of subsidiarity as such and the neo-Calvinist articulation of “sphere sovereignty” in the late nineteenth century and beyond.

2 thoughts on “Subsidiarity ‘From Below’”

Comments are closed.