Wink presents the original contextual meaning of Jesus as also a timeless meaning. He tries to draw from the bible a clear and simple message—one that contains everything necessary for contemporary Christians to take a stand for nonviolence.

I am sympathetic to what I perceive as Wink’s larger goal in this interpretation. He wants to remove the option of reading Jesus’s words as endorsing toleration of abuse. He is rightly aware of and duly burdened by too many examples in the history of Christendom in which the powerful have used a command like “do not resist evildoers” as a rationale for submission to injustice.

Wink’s approach throughout the Powers trilogy is fundamentally a reappropriation of the Biblical texts in light of contemporary concerns. Far from being a “really bad” reading of scripture, it is an excellent example of constructive Biblical theology… The answer he proposes is a wholesale reevaluation of both the Biblical conception of the Powers and Principalities, as well as their relevance to the modern world.

I ask whether they think Wink’s exegesis is correct. Many have been completely convinced; they think that Wink has provided very compelling evidence… But now that my students are certain that Wink has hit it out of the park, I can add another layer of complexity and uncertainty by sharing that I have doubts.

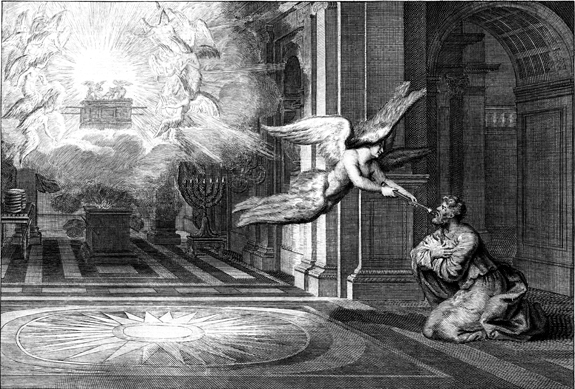

Isaiah’s call to prophesy judgment against Israel challenges us to remember God’s sovereignty over all political systems, even those that are disastrous in our eyes. Could God’s judgment be the decisive turning point toward healing?

Perhaps most crucially, one needs to know by whose authority any particular “text” is so named.

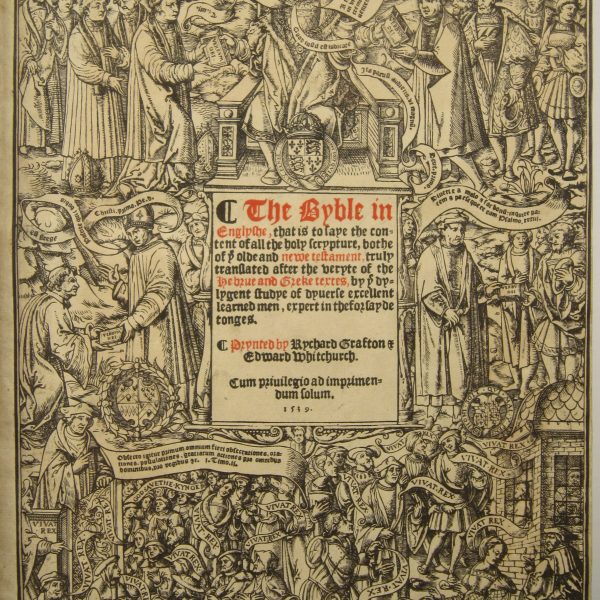

[The the second of three posts this week on Michael Walzer’s In God’s Shadow: Politics in the Hebrew Bible.] It is deeply satisfying to read a new book by Michael Walzer on the Hebrew bible. Certainly this is not Walzer’s first book on the Hebrew bible: Walzer’s earlier Exodus and Revolution already gives us a unique way to reimagine the revolutionary implications of the biblical text. With this new volume, Walzer’s writings on the bible continue to invigorate the way we can read this most ancient of texts. Michael Walzer’s In God’s Shadow sets a difficult task for itself. It reads the wide-ranging Hebrew bible to get a sense of how political institutions actually functioned in biblical times. This enterprise is more difficult than it sounds. Mining a work that consciously centers on historical and legalistic narrative for structural and procedural understandings about how political life actually works can be a counterintuitive project. It is a tribute to Walzer’s masterly sense of his craft and his nuanced readings of the biblical texts that he succeeds so well at his self-appointed task. Deliberately eschewing a philosophical or reductive (morally or otherwise) reading of the Hebrew bible, Walzer approaches these much-commented texts with another set of questions in mind: what role is left for politics in a world that, according to the bible at least, is governed by God?

In this column, I want to engage in what Reynolds Price once referred to as “a serious way of wondering” about Exodus 20: 15-18—i.e., the moment at which the Israelites experience the divine self-revelation at the foot of Mount Sinai. Normally, this passage is understood as a theophanic event. To the extent that it involves the constitution of a nation or polity, it has usually been understood as a theocracy. Its intellectual expression (insofar as it addresses the issue of covenantal authority grounded in divine self-revelation) would therefore take the form of a political theology. To the extent that we read the above passage in this way, we have already rendered a decision—the essential significance of the passage would lie in the divine self-revelation. The fear which the Israelites experienced would amount simply and solely to a fear of God. Conversely, an acceptance of the commandments would amount to an acceptance of the political theology undergirding the theocracy.