Amy Merrill Willis

Essays

The story of the encounter of Saul of Tarsus with the risen Christ on the road to Damascus is read in a number of differing ways, readings often shaped by what the church has become for us. At our juncture in the developing history of ‘The Way’ we have the opportunity to explore a different vantage point on this story, one shorn of much of the triumphalism of past readings and tempered by our uncertain times.

The account of the slaughter of the innocents rests like a deeply unsettling shadow upon the Christmas story, with its themes of God’s peace and presence. Yet, in reflecting upon this account, we may discover a profound new conception of the mode of God’s presence within our world and its tragedies.

We are the heirs of Elijah’s legacy. His influence is evident within later writings of the Bible, the Bible’s earliest commentators, and within the Bible-shaped parts of our own culture. But how might we assess our inheritance? Elijah is a hero of the covenant. Moses redivivus. A witness to God’s justice and mercy for those without power. And yet. . . Elijah’s legacy is also that of a “troubler” (1Kings 18:17-18). Although the prophet denied the title, the Jewish rabbinic tradition has not been afraid to name troubling features of his ministry. He seems more pre-occupied with his own difficulties than those of the people. He does not advocate for the Israelites. He uses violence.

That the resurrection is a beleaguered doctrine in North America and in Europe is hardly a new revelation. For all its technological wonders, modernity is uncomfortable with old-fashioned miracles. Pre-modern ways of talking about Jesus’ resurrection don’t translate easily for an audience that demands scientific corroboration and empirical evidence. As a result, Christianity has chastened and tamed this story in a number of ways.

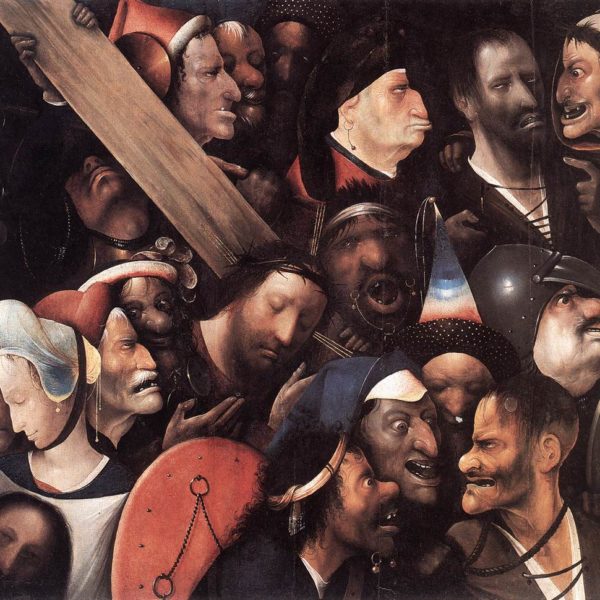

The lectionary readings for Epiphany bathe the reader in the language of light. Isaiah 60:1 commands the people of Zion to “Arise, shine; for your light has come.” Psalm 72:5 invokes those celestial light-givers, the sun and moon. And of course Matthew 2:2 gives us the splendid star-following magi and their sparkly gift of gold. In our most domesticated and tamed interpretations, we bask in the warm and cheerful glow emanating from these readings. Like our fireplaces keeping the gray winter at bay, these passages have become homey and cozy for many readers. Truth be told, I rather like that warm glow this time of year! Yet when these passages are let out of the house, they open up a larger landscape filled with things other than light and joy. Yes, they celebrate divine justice for the poor and the leader’s power to create it. They also illuminate the darkness and deception of power politics. They lift up the vulnerability of the divine sovereign made flesh, but also blatantly seek world dominion for the Davidic king. They rejoice in the manifestation of God, but also point to places where God‘s justice is eclipsed by political animals. In short, these passages for Epiphany disorient us about God and politics as much as they reveal God‘s relationship to the world…

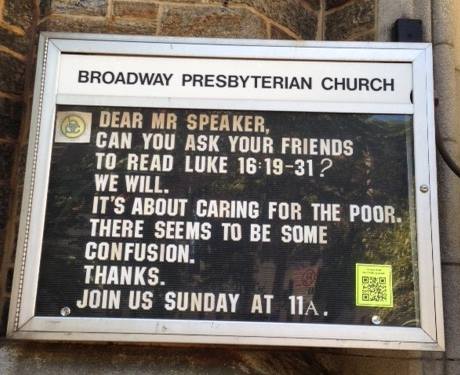

What makes for a good neighborhood? This is a question that American society has been struggling with in different ways for some time now. On one level, a response to this question might have something to do with a residential street dotted with beautiful lawns, white picket fences surrounding lovely homes, low crime rates, good real estate values, and maybe children playing in safety. On another level, however, the neighborhood can be a metaphor for the larger society. The question of what makes for a good American society is a much more divisive issue. It has been the source of rancorous disagreement throughout the election season. On this, and any political issue, election rhetoric becomes a contest of stories, a battle between narratives. Each party works to craft a persuasive narrative that can account for the present situation and also lift up its own vision of America’s future. At the same time, the narrative must offer bleak warnings about the dangerous values and vision of the other party. In the midst of such rancor, it can be a challenge to find a gracious vision of what the good neighborhood looks like. This week’s Old Testament lection from the second half of Ruth, however, can help us go a long way toward finding that gracious narrative. As last week’s post by Timothy Simpson pointed out, there is a lot more to the story of Ruth than usually meets the eye. It may not be typical to think of this story as embodying a vision for the good neighborhood, but the book is making some bold claims about precisely that…