The Book of Esther understands well the challenges of living in a world where one might have to juggle and negotiate different, even conflicting, identities and loyalties– one political, one ethnic and religious. But it is interesting that while these identities are sometimes open and sometimes undisclosed, they never correspond neatly to the categories of “public” political lives vs. “private” religious lives. Esther’s hidden religious identity makes claims on her public life as well as her private life…

It seems easy. So easy we can almost brush it off. Smile approvingly at the Sunday School teacher seated across the aisle from us in worship, and check one more thing off our spiritual to-do-list. Welcome little children? Done. We might ask ourselves, “How dense could these power grubbing disciples have been to miss so simple a point as this?”

But take a look across that same aisle once again… If your church is like many, there may be an usher giving a mother a dirty look as she walks her small child to the bathroom. Or a father putting his finger to his lip, afraid that his toddler’s whispers might disrupt someone. Or maybe a middle-aged gentleman checking the church’s giving record, calculating in his head what percent of the church’s income comes from his check. Or a young woman dressed just so, glancing at a hand mirror to check her make up….

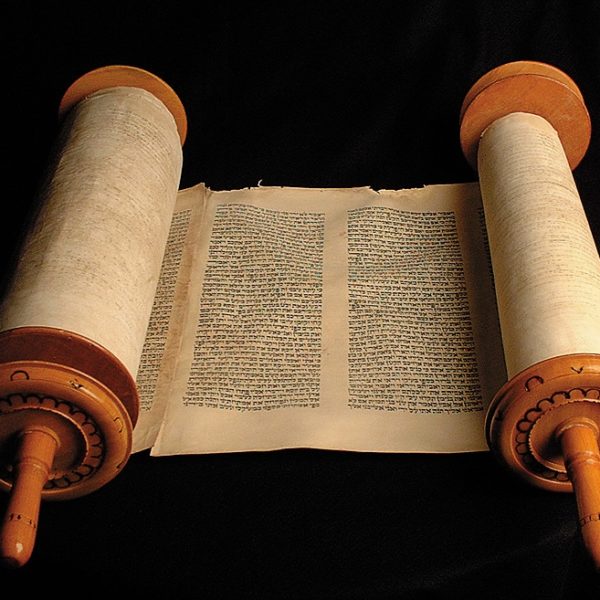

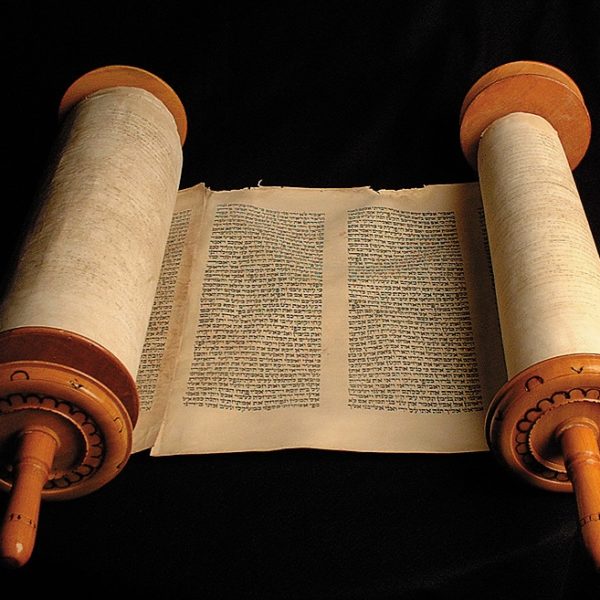

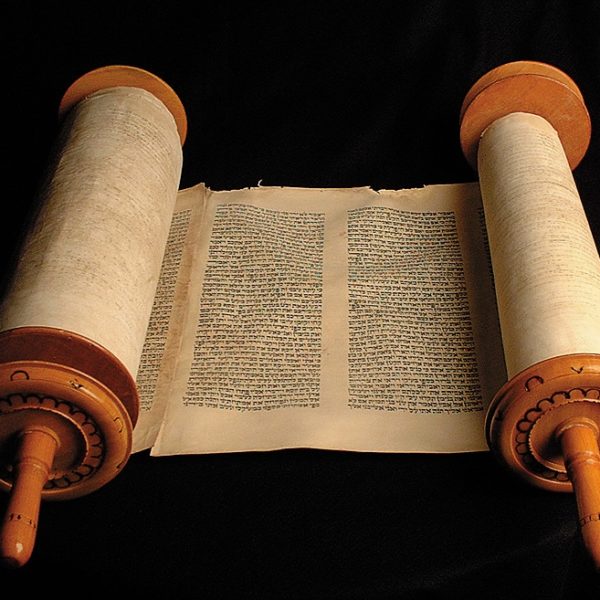

The Old Testament lection for this week from Isaiah 50 is one of the “Suffering Servant Songs,” (SSS) which, though there is nothing explicitly messianic in many of them, early Christianity nonetheless read as prophecies of Jesus. As George E. Nicklesburg demonstrated in a path-breaking article more than three decades ago in the Harvard Theological Review, the Suffering Servant wasV an important literary motif to which Israel returned repeatedly in an effort to make sense of its status as subordinate state in the larger geopolitical world in which was situated. Characters such as Joseph, Esther, and Daniel represented models of proper behavior and deportment on the part of Jews living in an alien moral universe fraught with everything from the seductive suggestions of compromise to the existential threats of extermination by the foreign powers which dominated them for so many centuries, first as the suzerain of the Israelites and then later, after 587, as their conquerors. The SSS are thus the poetic and prophetic complement to the narrative accounts of the righteous sufferers….

We don’t expect our politicians to say much about the poor, but what about the church? When was the last time you preached or heard a sermon on the poor? Not poverty, but the poor, and not as an illustration, but as a focal point. (We might ask the same thing about a college or seminary class that purports to be about the cultivation of wisdom or faith.) The readings from Proverbs and James (see below) refer to the poor directly. Both passages are striking because they go further than a soft paternalism that might urge us to care for the poor. James and Proverbs offer not an appeal to our altruism, the work of charity, or a political agenda or campaign. They are not looking for votes or a clear conscience. They see the poor as part of the community and concern for the poor as an integral part of the life of faith and wisdom….

Actually Jesus invites folks of all political and religious persuasions to a kind of humility. The human heart has, despite itself, a king of genius for corruptibility, no matter what rituals or traditions we make for ourselves. There is only one hope: to begin to see ourselves aright. And that is done by being in relation with God. This does not lie so much in the feel-good individualistic transformations beloved of conservative evangelicals, but in the challenging praxis of being part of a community of hope and forgiveness….

With this sort of starting point, we take an altogether different approach: our task, short of the full in-breaking of the Kingdom of God, can never be any partisan agenda. This is because anything short of the full consummation of the Kingdom of God will necessarily still be tainted, or worse, corrupted, by sin. All political activism then—in the sense of being active in talking to the contemporary powers-that-be in western culture—is always and necessarily ad hoc, never utopian, and never idealistic. We deal with each concrete question and issue as it arises, and seek to bear faithful witness as best we are able.

John’s gospel is replete with splendid imagery of the saving power of Jesus, so much so that it can be easy to wonder how the disciples could have even considered turning away from Jesus, even at the cross. But here we are, still a far cry from the cross and Jerusalem, long before the last supper and the cock’s crow, and rather than the masses that we’ve grown to expect to see coming out towards Jesus in droves, we are told that many who were following him turn away from Jesus en masse. How could this happen? What motivates those who leave? And what’s more, in the face of such harsh words–of inevitable tribulation ahead–what motivates those who stay? These are the politics of today’s gospel text…

This week’s lection is a well-loved, much-cited chestnut from which a thousand moralistic sermons have germinated. And with good reason. Solomon becomes king and when given the chance to have any wish fulfilled by God, chooses wisdom over the usual favorites, long life, wealth and power.

As even a cursory glance at this weeks lectionary reference will reveal, however, there are a couple of gaps in the text. The first is what happens just before Solomon dies, as he gets last minute instructions from David about scores that the family needs settling. The second is between the time that Solomon ascends to the throne, and the time Solomon and Yahweh have their little heart-to-heart. When you read that part that the lectionary omits, what you find is not Solomon sitting around having his daily quiet time in prayer and study of the scripture, but rather in the ruthless pursuit of control and the exercise of the royal prerogative of vengeance against the enemies of the monarchy…

Samuel speaks of God as working in and through the events to deliver “ruin on Absalom.” This is not simply God with us. It is God against us–whenever we treat our “kingdom” as if it was ours and ours alone. Both David and Absalom acted as if their people, the Kingdom of Israel, were their own plaything.

While the abuses of power and privilege in modern banking may not be as explicit as David’s crime, they are parallel. People in power tend not to consider the cost of their self-interest in communal terms. Most families who are facing foreclosure in New York City today are the victims of banks who regard a homeless child as a reasonable side effect of their profit motive just as David regarded Uriah’s death as a reasonable way to Bathsheba.

‘…as the food is set…a solid thumb and forefinger tears thunderous grey bread.’

For those of us who are inheritors of the Judeo-Christian tradition the word ‘bread’ crackles with connotation. Out of the simple truth that bread is one of the traditional staples of human living, endless symbolism flows: Bread can signify our basic human need for nourishment, it can act as a sign of the work of human hands and so on. Bread can be torn, scattered and gathered and, even in Rowan Williams’ poem Emmaus (quoted above), made to thunder. If some might treat ‘bread’ as a tired, overworked metaphor it also takes us to the heart of the Christian faith. The bread of the Eucharistic feast is no mere sign, it is sacrament….

The scathing criticisms of private property that we find in the mouth of Jesus are well-known. “Go, sell what you have,” he tells the rich man who asks for the secret of eternal life (Mark 10:21; Matthew 19:21; see also Luke 12:33). Again and again, we encounter the polemic against property, the possession of which is regarded as an evil and as a massive hindrance to joining the kingdom of God. Jesus valorises simplicity over luxury and forgoes the influence and power that comes with wealth. In short, everything about him stands against the deep values of the Hellenistic propertied classes. In the words of G.E.M. de Ste. Croix, “I am tempted to say that in this respect the opinions of Jesus were nearer to those of Bertholt Brecht than to those held by some of the Fathers of the Church and by some Christians today” (Ste. Croix 1981: 433).

I am less interested here in the twisting and turning by later exegetes to ameliorate these embarrassing texts, and my concern for now is not the Christian communist tradition that finds inspiration in these and other texts (Acts 2:44-5; 4:32-5). Instead, I suggest that this implacable opposition to property has a far deeper reason. Simply put, the very definition of private property, invented by the Romans a little over a century before the time of Jesus, is based upon slavery. That is, private property relies on the reduction of one human being to the status of thing (res) that is “owned” by another human being. Let me explain…..