Re-thinking the intersection of law and religion today tends to proceed from a concern for the limits of religious freedom and a critique of the foundational historical, social, and cultural presumptions about religion that are seen to undercut or frustrate the possibility of advancing religious freedom.

In light of the two kingdoms doctrine and the separation of church and state, understanding the appropriate form of Christian prayer for and engagement with the political realities of our societies can be complex. In Jeremiah’s message to an exiled people, we find a pattern for prayer in a pluralistic context, a calling that identifies our primary task to be one of seeking the common good and welfare of our communities, rather than one of submission or conversion.

. . . In other words, disasters such as Typhoon Haiyan confront us with the sobering reality that the deepest, deadliest and most intransigent problems we face today are social problems, not technical problems. We continue to deceive ourselves with the hope that if we can but increase our knowledge of the world, our technical know-how at problem-solving the riddles that nature poses for us, we can defeat death and disease.

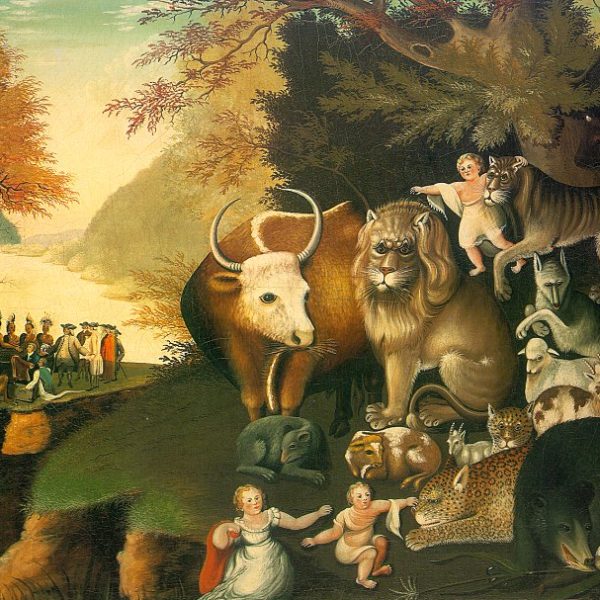

In Isaiah’s prophecy a young child serves as a sign puncturing the gloom of a dark political situation. The use of infants and young children to draw attention to God’s future within the book of Isaiah has significance for our own political visions. In regarding the sign of our children we can accomplish an existential turn from a politics driven by the selfish interests of our own generation to one of responsibility and hope for the well-being of those to come.

Despite the unending political chatter over global spying, the recent government shutdown, and now the misadventure of the Obama care rollout, I have also been pondering the meaning of something worth more obsessing about. . . . It amounts to the latest variation not of Murphy’s Law (“if something can go wrong, it will”), but what I have called Raschke’s Rule (“if you didn’t think people could be more foolish than they already are, just wait a day or so”).

As it was with Haggai, the real test of leadership is not necessarily the capacity to motivate people to action, but rather to keep them fixed on that same goal when it becomes clear that the rhetoric that moved them in the first place bears little resemblance to the actual situation in which they have to act.

. . . Often much more important than what people argue is how people argue. . . . Many whom we may have hastily taken as kindred spirits, because they happen to have reached some conclusion we moderns take for granted, turn out on closer inspection to have been motivated by wholly different concerns, so that the convergence is largely illusory. Others, however, whom we might be apt to dismiss as barbaric for their unenlightened ideas, turn out to have been strikingly liberal-minded.

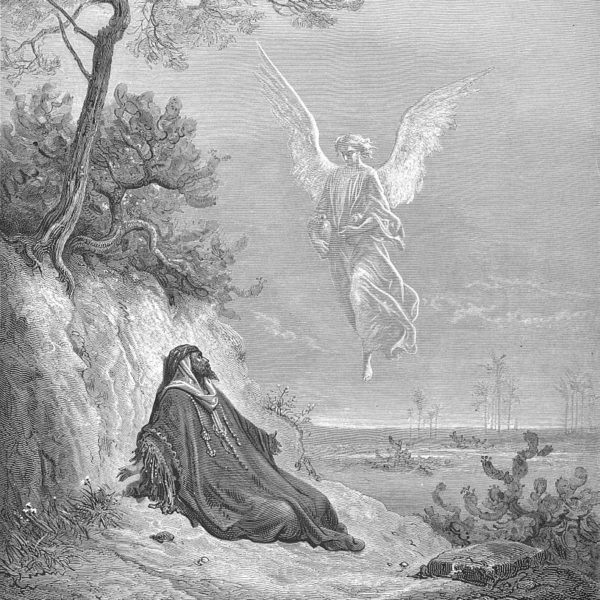

Elijah’s ministry takes place during the reign of king Ahab in the 9th century BC. The narrative about the prophet is expressly political. It depicts a political dissident who speaks against the powers of his day, with the main focus on promoting the worship of Yahweh and fighting against the worship of Baal. The prophet’s actions must be understood against a wider Near Eastern context where religion was completely intertwined with politics and where Yahweh was the national god of the Israelites.

For the sake of the following argument, I would like to grant the premises of Max Weber’s idealist argument: religion and culture (superstructure) are causative agents in socio-economic change. As is well known, Weber argued that Calvinism acted as a crucial vanishing mediator for capitalism. It provided the cultural, behavioural and religious framework that enabled capitalism to establish itself and gain ground.