“Most politicians represent an interest group, a community of people who vote for them and whose interests they serve. Nelson Mandela was different; he represented a community that did not yet exist, a community he hoped would come into being.” —Rowan Williams

At the very least we might say that both nonviolence and pacifism should attempt to understand and redirect violence. And maybe we should shelve the tired terms for a spell and speak of life-giving or death-dealing acts, which might reframe exhausting debates about property destruction. Pacifism should not be at odds with physical force, with the force of physicality such as sit-ins, strikes, human chains, roadblocks, or even strategic property destruction.

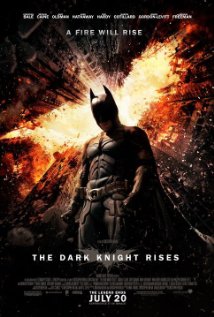

Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy is obsessed with the question: what are the conditions of possibility for political judgment? Judgment, as Oliver O’Donovan has written in The Ways of Judgment, “both pronounces retrospectively on, and clears space prospectively for, actions that are performed within a community” and is therefore “subject to criteria of truth, on the one hand, and to criteria of effectiveness on the other” (9). Although judgment must meet both criteria, very often in the world of politics, they appear to be in rivalry. Truth-telling, in a world of fickle voters and predatory media, in a world of terrorists and hidden threats, can seem like a very unwise proposition, a luxury that must be dispensed with if order and justice are to be preserved. This tension haunts Nolan’s trilogy.