We are happy to announce the publication of Vol. 16, Issue 3 of our journal, Political Theology. Unlike several recent issues, this issue is not organized around a single theme, but brings together a range of high-quality contributions on diverse topics in contemporary political theology.

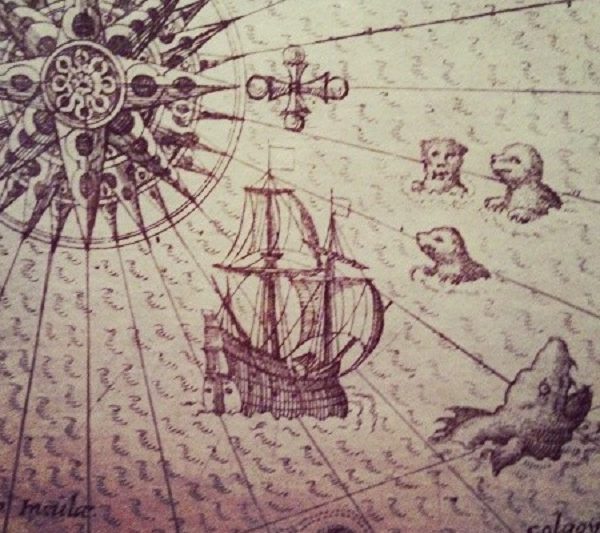

The storm at sea is one of the most potent experiences and images of chaos. Jesus’ miraculous calming of the storm is an image, not merely of his power with regard to nature, but also of his mastery over the chaotic political elements that threaten us.

If Dostoyevsky foresaw the rise of the 20th century totalitarian states as the father figures who would feed the masses in the first temptation, what did Dostoyevsky foresee here with regards to his feared future Catholic theocracy? What Dostoyevsky saw was how the captivating of the conscience through miraculous ecstasy could manifest itself, in games and permissiveness.

. . . In other words, Chappie can be read as an allegory that calls for us to recognize our ill-treatment of the other, and the film seeks an alternative ethic that does not recourse immediately or uncritically to fear or hostility, leading to violence. We are to be more embracing of the ‘other’ who is, ultimately, more complex than we might first assume, and is never entirely ‘other’.

In May 2014, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi travelled to the riverside holy city of Varanasi to worship mother goddess Ganges in gratitude for his victory in the national elections. This grand self-promotional gesture by a prominent Hindu nationalist politician illustrates how religion and politics remain enmeshed in India. Even though the democratic constitution of the nation-state has been modeled on western varieties of secularism, everyday politics is infused with religious iconographies.