For nearly two decades, Wesley Theological Seminary has sponsored the National Capital Semester for Seminarians (NCSS), a program which immerses students from Wesley and other seminaries around the country in the politics and policymaking of Washington and the ways people of faith intersect in those spaces. When Dr. Shaun Casey, the long time coordinator of the program, left to join the faith outreach office at the U.S. Department of State upon request of Secretary of State John Kerry, I stepped in to help direct the program.

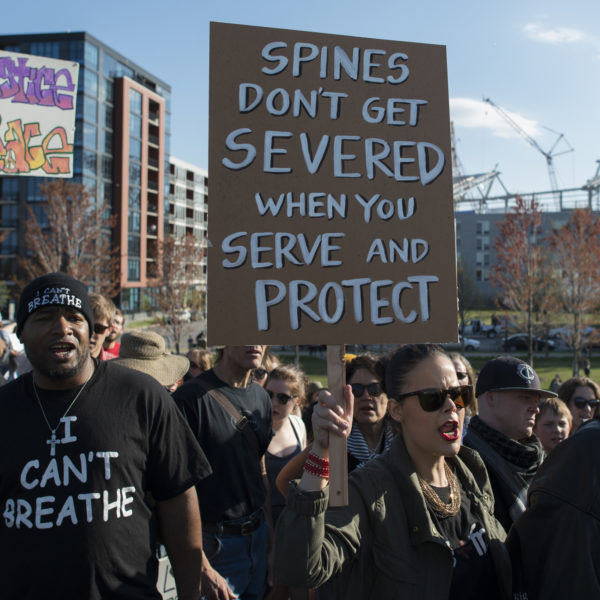

In this week’s edition of QUICK TAKES, we take a hard look at the race crisis in America in light of the death of Freddie Gray and the turmoil in Baltimore. We posed the following questions to our contributors: What do the seemingly regular reports of deaths of young black men at the hands of police officers as well as the resulting protests tell us about the conditions of race and race relations today?

My interest in teaching a course on Political Theology came from my research on Simone Weil. I wanted to understand how the area of political theology could help me interpret Weil’s oeuvre, which often focuses on the intersection of politics and religion. To that end I decided to teach a course in the Fall of 2011 that would explore the historic development of the concept “political theology.” The course would consider how the western tradition has “thought” the intersection of politics/theology.

With the start of the 2016 election season now coinciding with the publication of Kingdom Politics: In Search of a New Political Imagination for Today’s Church, we are reminded of the beginnings of this book project. As the 2012 election cycle began picking up steam, we embarked on a journey to research the ways five diverse congregations engage and avoid politics, and the reasons they give for doing so.

The familiarity of the 23rd Psalm can blind us to the striking political dimensions of its message: YHWH is the shepherd of the king, protecting him from enemies and granting his kingdom prosperity. Close reflection upon this psalm may also suggest some significant applications within the contemporary world.

It is with great sadness that we note the death of a former editor, the Rev Dr Tim Simpson. Tim died on Tuesday 7th April after complications associated with his battle with cancer.

There were many aspects to Tim’s life and ministry, more than can be covered here. He was a relentless teacher, preacher, pastor and campaigner for justice and peace. Other places will record his important contribution to many different churches, universities and colleges. For us Tim was a scholar, an intellectual and an editor. His death feels like the passing of an era for the journal and for the discipline as a whole.