This reading of Thomas’s story, for me, is a powerful reminder that faith is not a straight line from doubt to belief. It is a complex journey through relationship, rupture, and repair. From the perspective of self-psychology, Thomas represents not merely an individual struggling with uncertainty, but anyone who has experienced the pain of exclusion (a break in connection).

If we want to experience the full effect of Easter, we must recognize that it’s not just about Jesus…it sends ripples through the cosmos as it signals the dismantling of worldly kingdoms built on exploitation and invites us to participate instead in a social order that reflects God’s intentions for the flourishing of all.

While deeply engaged with the concerns of everyday life such as healing, feeding, and engaging people in matters of justice and community, Jesus offers an alternative vision: one shaped by self-giving love and radical faithfulness to God’s kingdom, rather than by the structures and strategies of empire.

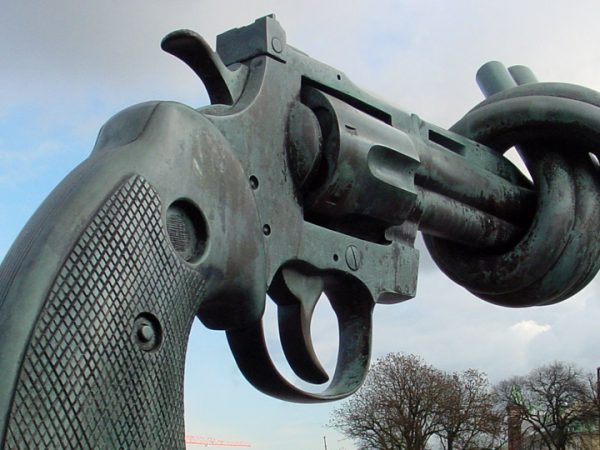

The language of ‘right to defense’ has been consistently deployed to legitimate Israel’s general military strategy and ongoing U.S. provision of weapons as its policy. Meanwhile, Pope Francis consistently calls for an end to the mass atrocity of war… Something drastically needs to change.

In a time of intense economic anxiety, both individuals and communities need to reflect on the call in John 12 to claim their responsibility to shun greed, resisting it with a seemingly foolish kind of generosity that parallels Jesus’s becoming poor for the sake of others.

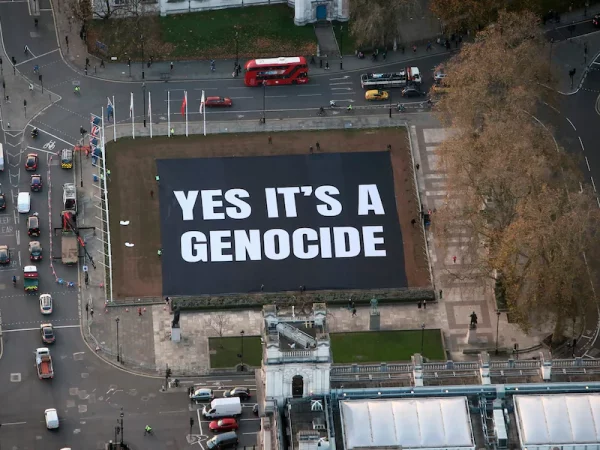

This theological dimension, which does not exclude messianism but coexists with it, is not new to Zionism and has been present in it from its inception; articulating it will therefore contribute not only to understanding the history of Zionism, which is far from being as peace-seeking as it often tells itself, but also to understanding the wide Israeli support of the genocidal war on Gaza.

The Western inability to recognize Palestinians as fully human is often attributed to Islamophobia, framed as a post-9/11 construct that portrays Muslim violence as a threat to the liberal West. However, this perspective remains superficial. To truly understand the roots of Western hatred, we must look deeper—beyond contemporary narratives—into the ideological foundations of Western thought.