Please forgive this brief preface:

This post is part of something larger…something much, much larger: a blog tour put together by Homebrewed Christianity meant to investigate and critique Clayton Crockett and Jeffrey Robbins’ recently published “Religion, Politics, and the Earth” (hereafter RPE). If you aren’t already familiar with their book, you can now become an expert! If you’re looking for a quick introduction, click here for Homebrewed’s podcast/interview, or here for a helpful (but unrelated to the blog tour) review on AUFS. In brief, using topics such as digital culture, logic, energy, art, etc., Crockett and Robbins have written a politico-theological and non-reductive materialist manifesto by which we are provided the means to reimagine a future of our world. Also, at the bottom of this post, there is a link to the other blogs that already have or will have posts this week! If you want to buy the book—and it IS a great/exciting/interesting read—click here.

________________________

My goal here is to provide a layout and a critique of Chapter 4, “Art”. This chapter was co-authored by artist, Michael W. Wilson (his website).

As the entirety of the book makes clear, society, as a system, currently functions at the level of the Global: commercial practices/expectations, uniform technologies, franchised markets, and the inescapability of immediate communication. As Niklas Luhmann began his work on the grip of mass media, “whatever we know about…the world in which we live, we know through the mass media.” It seems, then, that we always already know what we know and what we don’t know based on the conditions provided by the unstoppable force—that Crockett and Robbins see as being fueled by capitalism—called globalization. This is not to suggest that more intimate environments no longer exist, rather that the points of reference of social relations are never isolated from the environments around them. It is on the global stage that RPE insists art imagine itself as a renewing and generating form of cultural vitality, drawing attention to and disrupting the dominant forces of social power, and becoming plastic with its potential to be made manifest in a multiplicity of mediums. Based on their vision, to be effective in the 21st century, art must continually reimagine how it can become blatantly political: balancing a fine line between creative activism and becoming something that would fit into the conveniently malleable (to those not involved in the artistic processes) category called ‘terrorism.’

As the entirety of the book makes clear, society, as a system, currently functions at the level of the Global: commercial practices/expectations, uniform technologies, franchised markets, and the inescapability of immediate communication. As Niklas Luhmann began his work on the grip of mass media, “whatever we know about…the world in which we live, we know through the mass media.” It seems, then, that we always already know what we know and what we don’t know based on the conditions provided by the unstoppable force—that Crockett and Robbins see as being fueled by capitalism—called globalization. This is not to suggest that more intimate environments no longer exist, rather that the points of reference of social relations are never isolated from the environments around them. It is on the global stage that RPE insists art imagine itself as a renewing and generating form of cultural vitality, drawing attention to and disrupting the dominant forces of social power, and becoming plastic with its potential to be made manifest in a multiplicity of mediums. Based on their vision, to be effective in the 21st century, art must continually reimagine how it can become blatantly political: balancing a fine line between creative activism and becoming something that would fit into the conveniently malleable (to those not involved in the artistic processes) category called ‘terrorism.’

The chapter is divided into two main sections: first, the philosophical and historical context of modern art is outlined through the mid-late 20th century; second, they assert the “revolutionary claim” (63) that artists can activate the latent ability of art to stimulate a new understanding of the sublime, onethat is separate from the subjectivity provided by capitalism: a “communist sublime” (67). Given its brevity, the first section clearly and concisely tells the history of modern art. Interestingly, however, they begin with the claim that, since the 18th century, art has taken over the social role that had previously been assigned to religion: the expression of spiritual values, the force that maintained social order, and the provider of distractions from political and economic brutality. In their claim, they brilliantly recognize art as a surplus activity, “ a primal response to death” (56).

Crockett and Robbins begin with Kant’s investigation of beauty in order to bring foreword the concept of the sublime. The sublime was a hugely formative notion for the development of modern art. The sublime occurs when the limits of one’s imagination are reached; there is a contrast of senses: a fear that one will lose oneself in the abyss, and a determination to understand what is beyond oneself. Importantly, Crockett and Robbins make it clear that the sublime is not an object, but a relationship. This relationship was the impetus for artists, who, nearing the 20th century, began to refuse the limits of representation and adopted a decidedly nonrepresentational form of art making. Nietzsche’s “overman” finalized art’s replacement of religion, claiming that art was the supreme assertion of the will; by artistically generating the sublime experience, the veil that separates the self and the other is torn away (60).

To conclude their history, RPE connects the themes of (non)representation, the sublime, and philosophy to the avant-garde movement that began in the middle of the 20th century. To make this connection they review the work of the Dadaists, who were reacting to the violent technological warfare of WWI, the Surrealists, who continued an antisublime that the Dadaist incited, and the Situationists, who took the antisublime to its utopian extreme with their gestures that heightened the subjective alienation produced by capitalist exploitation. The problem that Crockett and Robbins have set up is this: the way that the sublime has been conceived of is conditioned by the reality of capitalism and the subjectivity that it allows.

Their reading of history here seems closely aligned with Adorno and Horkheimer’s conception of a “culture industry.” Every creative or popular product eventually becomes commodified in order to guarantee that the masses submit to the interests of the market; the revolutionary art movements of history have all fought this oppression, but have one by one been absorbed into its processes of production. The artistic shifts outlined in RPE—representational, to nonrepresentational, to abstraction, to conceptual and performance—are compared with the modes of the capitalist market. Artists continually attempt to surpass the logic of capitalism but never prevail as victorious: art either loses its essence apart from media, capital, and productions (as with Pop-art), or continually provide the market new ways into the everydayness of the viewers (as with Happenings). This narration is far from unfamiliar to any MFA student in the West (…such is the way Institutional Art has taught students to critique), but the real greatness achieved in the first half of this chapter is that it reintroduces theologians to the general temper of artist in the 21st century—filling a gap of dialogue that is sorely lacking today.

From the historical context provided, and using Guy Debord (of the Situationists) as a turning point, Crockett and Robbins argue that it is the job of the artists to “free subjectivity from the sublime force of capital” (63). For Debord, a “situation” was a moment or set of circumstances that was deliberately constructed as a set of events that transformed the banal into the passionate. For the Situationists, and for Crockett and Robbins, fostering such “situations” is overtly political and meant to challenge hegemonic thought. Unfortunate, however, is the fact that since the middle of the century, museums, galleries, and studio practices have institutionalized the aesthetic paradigm that rendered artist’s actions political. The authors use the voice of Felix Guattari to affirm that, in order to be materially meaningful, art must become an activity of “reframing…and a reinvention of the subject itself” (64). If successful, artists will have created a new way of representing life and of living with aesthetics. But that cannot be an end in itself—Crockett and Robbins want to see art reinventing what it means to live together in rather than just on the world. They conclude by connecting Josef Beuys concept, that thought can be a socially-sculptural activity, with Catherine Malabou’s conception of plasticity: the ability to give, receive, and autodestruct form. Resultantly, RPE suggests that social and biological life, as well as the world itself, can become a new form of living, sculptural art. Such is the nature of what they are calling the “communist sublime”: a sublime experience that is free of alienation from one’s time, history, and importantly one’s own self. Here, the “revolution” is sublime, sublime becoming.

Sadly, Crockett and Robbins provide no existing examples of who is doing this art or what it might look like. In that regard, the chapter ends rather ambiguously as if such a task was self-evident. The only thing provided is a way to better imagine an idealized world. The history that they have provided in the first section of the chapter is very accessible and very informative, covering a lot of ground without getting obsessively technical or making any sweeping generalizations. The difficult part is that, because they recorded the history so poignantly, I was hoping that their conclusion would be as informed and concrete. It is not that they were not informed at all, but that it only appears as if they are communicating critical theory, and are somewhat ignorant of the state of contemporary art today. It is at this point that I am torn with how to understand their propositional conclusion. There are two major issues I’ll address: the ambivalence that results from their rhetoric, and the ambiguity of how a communist sublime might occur.

On the one hand, art graduate programs across the country use critical theory as their sole required texts (if they have required texts). This is not necessarily a bad thing, but that the rhetoric that is employed in this chapter of RPE comes across not as radical, but as expected in the institution—some would take that as a good thing, other would take it as something that numbs artists to the reality of social struggle. Regardless, many of the most progressive artists (whether you enjoy their work or not) seem to have already recognized that imagining a sublime outside of capitalism is a mistake; one must come through it. For instance, Dis Magazine, or the work of Ian Cheng, defiantly takes capitalism at its word; by amplifying the emptiness of capitalism their work is filled with politically anti-capitalist meaning. Or take Brad Troemel’s use of Tumblr, Etsy, and Silk Road: here he smartly asks, not, “How can art function more successfully” but “What happens after art?” This is a pertinent question: What happens once art has become decontextualized as art and the viewer no longer even recognizes what they see as art? These three examples are versions of the first fully-native Internet artists. They are at once fascinating and appalling—teetering between angst for annihilation and a post-nihilistic ultra-western sublime. On the other hand, the language concerning art in this chapter is desperately needed within the context of most other disciplines. As a student of theology, who has also spent time in art school, and has a wife in an MFA program in LA, I cannot help but notice a striking difference between the way artists talk about art and theologians talk about it…as if one were more pressing than the other.

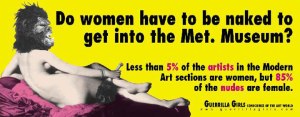

Second, because they provide no artists as examples, it is not very clear as to what or whom they are talking about. To what experience is the “communist sublime” comparable. I cannot tell if I am wrong to want to imagine any of the artists I have heard of or seen in galleries/museums, or if they want me to recognize any type of activism asart. If such an example had been provided much of the vague-ness of the final two pages (67-68) would have been avoided. While this point did encourage me to rethink what I considered as ‘art,’ I was unaware as to what end it was pointing to. For example, it would have been thought-provoking if they had suggested that Occupy could/should be viewed as ‘social sculpture’ (given that a general critique is that no one knows what Occupy was exactly). Oppositely, I was also left wondering what they considered to be harmful art, or art that perpetuated the current model. Where does something like Martin Kippenberger’s art stand? His art was challenging in that he produced so much, and at the same time, refused to be bound to any one genre or discipline. While in the past few years the art market has auctioned his work for millions of dollars, his art still challenges the standard conventions. I assume that Crockett and Robbins would like to see more work in the vein of the Guerrilla Girls, Group Material, or Wafaa Bilal…but as I already noted, I am not sure. A statement like, “rematerialize in the streets, the networks, the institutions, and the bodies of the artists themselves,” (68) disregards much of contemporary art if it is spoken with no tangible examples (as it is in RPE), as if were not already happening. Therefore, to the artist, this chapter is paralyzing; to the radical theologian, it is mystifying.

I do not want to be overly negative about this chapter ( I truly loved and wholly recommend the book) but the potential the chapter on art carries is lost in the final two or three pages. It was not disappointing because they are coming at art from a drastically different perspective than I am, but because the clarity of the first two-thirds was lost in how they synthesized their proposal. The point is that I am not exactly sure what Crockett and Robbins are even looking for in art other than a revolution (and what artist isn’t?). In this sense, RPE is itself a reflection of what they aim to deem “sublime.” And because the sublime is not an object, but a relationship, this chapter seems to propose that a “revolution” will never actually occur, only the invention and re-invention of the artistic production of the sublime—something grand beyond the limits of our imagination.

_______________________

Don’t forget to check out the other posts on the blog tour for the book!

HERE IS A LINK TO THE BLOG LIST

_______________________

Scott J. Cowan currently lives in Los Angeles and is pursuing a Masters of Theology at Fuller Theological Seminary. His interests in cultural criticism, philosophy, and investigating social structures in language have an influence on his approach towards theology. Other than theological studies, Scott has a background/interest in photography and art history/theory.

How much more manipulative in-your-face ugliness does humankind need?

I much prefer the Illuminated Understanding of Art & Culture communicated in these 4 references – the last two are about politics too (the necessary politics of the future)

http://www.aboutadidam.org/readings/art_is_love/index.html

http://www.adidaupclose.org/Art_and_Photography/rebirth_of_sacred_art.html

The Realization of The Beautiful

http://www.adidamla.org/newsletters/newsletter-aprilmay2006.pdf

http://www.ispeace723.org

Plus on the non-human inhabitants of this mostly non-human world

http://sacredcamelgardens.com

http://www.fearnomorezoo.org/literature/observe_learn.php