In July 2025, the Vatican organized a first-of-its-kind gathering: a festival for Catholic influencers. The event drew clergy as well as lay content creators from around the world for an opportunity to reflect on the role of digital media in evangelization.

Ostensibly a celebration, the festival also revealed the Church’s growing concern over the diffuse and unruly media landscape where Catholic identity now circulates. How does the Vatican’s meeting with Catholic influencers reveal the decline of institutional authority in an algorithm-driven culture?

In a digital environment where anyone with a smartphone can become a leading religious voice, Church leadership seemed eager to reassert its authority, or at least to harness the energy of digital evangelism for official ends.

But the summit reveals a fundamental tension at the heart of life in the age of social media. Dominated by culture-war rhetoric and sometimes openly critical of the bishops and of the late Pope Francis, many of these influencers reflect the broader populist polarization of political and religious discourse.

The rise of digital hyperconnectivity—the condition in which communication is constant, ubiquitous, and immediate—has reshaped the dynamics of institutional authority. Authority isn’t just inherited, it’s performed and recognized. These Catholic influencers project an ecclesiastical authority not sustained by Rome, but rather by the likes, shares, and algorithmic circulation of a hyperconnected public.

Scholars of media and internet studies have been discussing “platform society” (José van Dijck) or “platformed sociality” (Couldry and Hepp) for almost a decade now. These studies highlight how digital platforms provide personalized content and services while bypassing traditional institutional structures. Our always-on hyperconnectivity has disrupted older institutions ranging from markets to democratic processes. Platformitization and hyperconnectivity now play a central role in the organization of societies, and the Catholic Church is no exception.

What is a “Catholic influencer” on the open web?

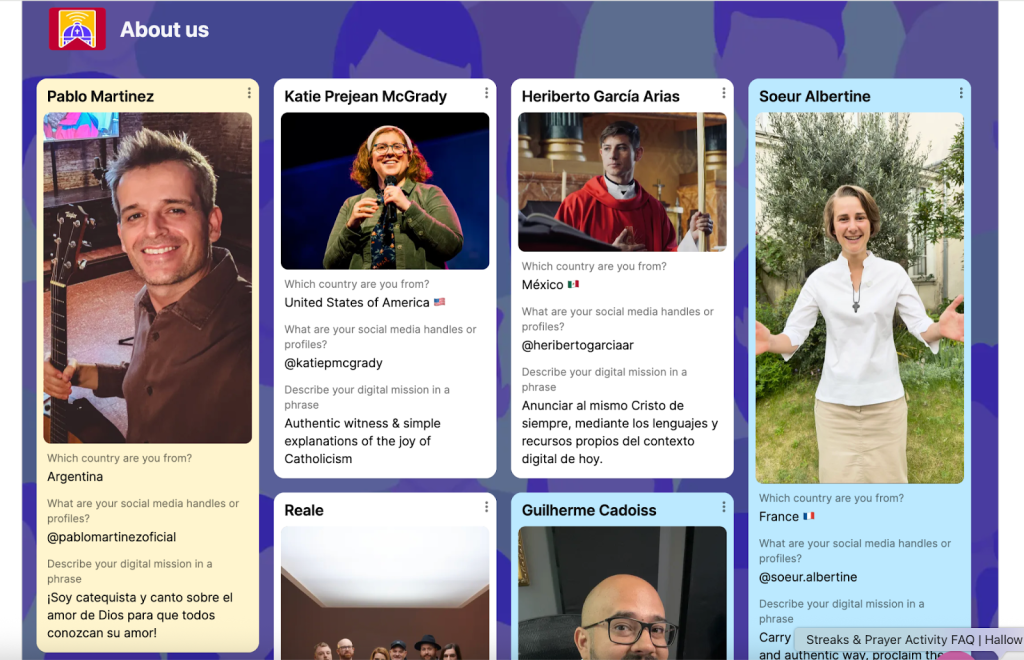

Source: Jubilee of Digital Missionaries and Catholic Influencers website

The rise of influencer culture reveals how digital media is reshaping what Catholicism looks and sounds like today. Some creators position themselves as orthodox and operate within church-approved media networks. One creator invited to the summit (and featured on the Vatican website), Katie Prejean McGrady, is a well-known podcast host, author, and Vatican analyst for CNN. A handful of small-scale creators were also invited to the summit, like 51-year-old Angie Bosio, who sells saint magnets to a modest Instagram following of about 600. Yet with only about a thousand influencers invited to the Vatican’s recent digital summit, it’s clear that most of the internet operates outside “official” Catholic oversight.

Online, institutional boundaries blur: the Church cannot control the circulation of meaning or imagery. Catholic aesthetics and rhetoric now circulate in a hyperconnected media environment where devotional imagery, lifestyle branding, and political commentary mix freely. For many, especially some younger folks, converts, and the “chronically online,” contemporary Catholicism is being shaped as much by internet culture as by papal pronouncements.

Because Catholic content spreads algorithmically—not only through deliberate follows but through overlapping likes, shares, and recommendation systems—it is linked to other content ecosystems: weightlifting and wellness culture (see Joe Jarell), right-wing political media (see self-described Catholic Christian Nationalist Sarah Stock), other confessional communities (for example, Catholic influencer Lila Rose often appears with Reformed Baptist influencer Allie Beth Stuckey). These algorithmic proximities mean that the platforms themselves, and those who design their recommendation systems, play an outsized role in defining what Catholicism looks like, feels like, and values online.

Religious Influence, or Corporate Marketing?

In his opening remarks, Vatican communications chief Paolo Ruffini encouraged the influencers to consider to what extent “we have allowed ourselves to adopt the language of corporate marketing.” Catholic leaders worry that online evangelization has become indistinguishable from branding, with faith packaged as “cultural content” optimized for clicks.

But the fusion of religious authority and popular culture is hardly new. Religious discourse has always been embedded in broader political and cultural logics. From medieval sermons borrowed from courtly rhetoric to twentieth-century contemporary Christian music, religious communities reflect pop culture.

So why does this moment feel different?

The answer lies in the decline of gatekeepers and broad access to cultural participation brought by hyperconnectivity. For most of the twentieth century, religious communication relied on mediated channels—radio, television, publishing houses—where access was controlled. To succeed required institutional approval, financial backing, or at least some infrastructural gatekeeping.

The iPhone changed all that. Now, a single priest with a TikTok account or a laywoman with an Instagram following can reach millions of users without passing through any hierarchy at all. Authority is increasingly distributed and, now, often determined by the logics of virality. In other words, content with a high emotional resonance (including rage) will circulate widely, encouraging provocative and antagonistic content.

Reading between the lines of Ruffini’s question, the concern is not simply that influencers adopt “marketing” language, but that they wield influence without even the guise of institutional mediation. The discourse that claims to speak eternal truth is now entangled with platform logics designed to maximize engagement.

The concern is not only about style, but rather a question of legitimacy itself: who will be successful in defining Catholicism in the digital age?

Followers, or Disciples?

Another telling moment came when Ruffini reminded attendees: “We are not here to chase followers or brand ourselves, but to be missionary disciples in this digital age.” The exhortation points to the heart of the tension.

In practice, the line between “digital missionary” and media influencer is nonexistent. For many content creators, their livelihood depends on engagement metrics. To survive as an influencer is to constantly generate content, maintain visibility, and cultivate a brand. Far from incidental, follower counts and brand identity are the very conditions that make “digital evangelization” possible.

Here Brubaker’s notion of hyperconnectivity again clarifies the dilemma: digital communication does not simply enable new forms of religious authority; it demands continuous participation in platformed attention economies. Authority accrues not to those who wait silently for disciples but to those who post consistently, generate engagement, and ride the algorithm.

To insist that influencers should not “chase followers” is to invoke a discourse of transcendent authority: true sacred witness should stand apart from worldly markets. The influencer summit thus dramatizes the paradox: religious authorities need digital missionaries but also want these influencers to somehow avoid the very logics that make them influential.

The Battle Over Authority

What is at stake in all this is not just communication strategies but the very nature of institutional authority– religious or otherwise. For centuries, Catholic authority operated through hierarchical mediation: papal pronouncements, episcopal teaching, catechisms, parish sermons. Today, authority is radically decentralized. Lay influencers can amass larger audiences than local bishops; a meme can carry more persuasive power than a magisterial document.

Hyperconnectivity amplifies this shift. The collapse of communication barriers creates a situation in which everyone is a potential authority. Within Catholicism, this means authority is contested not just between Rome and local churches but among lay influencers, anonymous meme accounts, and even algorithms set in motion by the platform’s engineers and technocrats. Authority emerges less from ordination or office than from affect, aesthetic, and algorithmic circulation.

Toward a Platform Catholicism

The Vatican’s Jubilee summit with influencers thus exposes a deeper transformation underway: Catholic authority is being renegotiated in the crucible of platform capitalism and digital hyperconnectivity.

The challenge for the Church is not only whether influencers can be “missionary disciples” rather than “brands,” but whether institutional authority itself can withstand the pressures of a platform environment that prizes virality, speed, and abundance.

The Church has never controlled living, breathing Catholics—their beliefs, practices, communities, or everyday lives. Throughout history, Catholics have engaged in practices not officially sanctioned, and what eventually received official approval was always entangled in social, political, and economic forces. What feels different today is that the veil has been lifted: in the hyperconnected age, we can see everyone doing and saying whatever they want. This visibility makes it feel as though the Vatican has lost authority—and perhaps that perception is precisely the difference.

Share This

Share this post with your friends!