We are the heirs of Elijah’s legacy. His influence is evident within later writings of the Bible, the Bible’s earliest commentators, and within the Bible-shaped parts of our own culture. But how might we assess our inheritance? Elijah is a hero of the covenant. Moses redivivus. A witness to God’s justice and mercy for those without power. And yet. . . Elijah’s legacy is also that of a “troubler” (1Kings 18:17-18). Although the prophet denied the title, the Jewish rabbinic tradition has not been afraid to name troubling features of his ministry. He seems more pre-occupied with his own difficulties than those of the people. He does not advocate for the Israelites. He uses violence.

Increasingly in liturgical circles it is becoming politically incorrect to talk about the “kingship” of Christ. Such a term now brings with it all the baggage of patriarchal interpretations of the biblical text. It calls to mind the exploitation brought about by colonial powers, abuses of power at the hands of politicians, and perhaps every abuse of power—abuses which represent heinous tragedy and sin. However, while we lament such abuse it is important to remember that power, in political terms, is itself neutral. It is a gift given by God in creation, which when wielded in the hands of human beings can be used for either selfish or selfless purposes (usually with correspondingly negative or positive results). Unfortunately, too often we as human beings struggle to monopolize power for our own sakes and consequently abuses occur…

In contemporary Western society we like to pride ourselves on having done away with what we would term ‘archaic’ systems, such as slavery. And so, when we hear such a system mentioned or even alluded to in a text like John 8:31-36, it is easy to write Jesus’ words off as anachronistic to our more ‘civilized’ approach. If we’re among the majority of such Westerners who know of no slavery in our ancestral background (or, if we do, whose ancestors were the slaveholders), then we may be tempted to object with Jesus’ disciples:

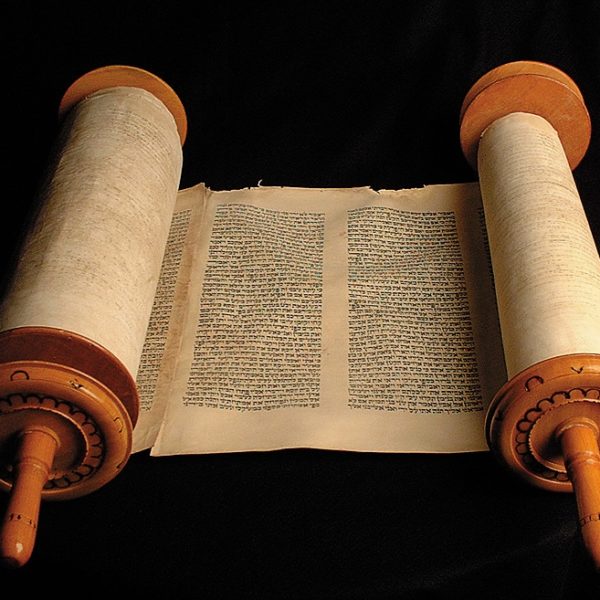

“‘We are descendants of Abraham and have never been slaves to anyone. What do you mean by saying, “You will be made free”?’” (8:33)

The first disciples resisted Jesus’ slave imagery, but not without irony. After all, the children of Abraham with whom they identify are the same children of Jacob who traveled to Egypt and were made slaves. Moses and Aaron led their ancestors through the wilderness so that they—the disciples, all the Jews, and by extension believers today—are children of the exodus; children for whom the reality of slavery is very real and near. And yet they resist this, practicing a form of selective amnesia rather than think of themselves as slaves.

It seems easy. So easy we can almost brush it off. Smile approvingly at the Sunday School teacher seated across the aisle from us in worship, and check one more thing off our spiritual to-do-list. Welcome little children? Done. We might ask ourselves, “How dense could these power grubbing disciples have been to miss so simple a point as this?”

But take a look across that same aisle once again… If your church is like many, there may be an usher giving a mother a dirty look as she walks her small child to the bathroom. Or a father putting his finger to his lip, afraid that his toddler’s whispers might disrupt someone. Or maybe a middle-aged gentleman checking the church’s giving record, calculating in his head what percent of the church’s income comes from his check. Or a young woman dressed just so, glancing at a hand mirror to check her make up….

John’s gospel is replete with splendid imagery of the saving power of Jesus, so much so that it can be easy to wonder how the disciples could have even considered turning away from Jesus, even at the cross. But here we are, still a far cry from the cross and Jerusalem, long before the last supper and the cock’s crow, and rather than the masses that we’ve grown to expect to see coming out towards Jesus in droves, we are told that many who were following him turn away from Jesus en masse. How could this happen? What motivates those who leave? And what’s more, in the face of such harsh words–of inevitable tribulation ahead–what motivates those who stay? These are the politics of today’s gospel text…

While the abuses of power and privilege in modern banking may not be as explicit as David’s crime, they are parallel. People in power tend not to consider the cost of their self-interest in communal terms. Most families who are facing foreclosure in New York City today are the victims of banks who regard a homeless child as a reasonable side effect of their profit motive just as David regarded Uriah’s death as a reasonable way to Bathsheba.

The author of Ephesians is addressing the conflict between Jew and Gentile Christians (“the cut/circumcised” and “the uncut/uncircumcised”). The politics of this text could be boiled down to the first century conflict between these two groups. It’s a definition so basic and so simple that it belongs in a Politics 101 course. Where it gets interesting, however, is not how one defines the conflict, but how the author of Ephesians deals with it…..