Upon completing the book, I wanted to turn my attention to my other scholarly interests. I wanted to look away. However, the book, despite whatever shortcomings it has, seems to have struck a chord. Reading groups have used it on several campuses. I have given more talks already since its 2021 publication than about any other topic over the course of my career.

I have been interviewing thirty persons, mostly forcibly-terminated professors from Protestant and Catholic institutions, and several professionals who work with them. Their stories demonstrate a stunning depth of disillusionment. The majority of these often-ordained religionists feel so betrayed by the church that they – and often their families – refuse to be part of it anymore.

Most disciplines in the university are less about workforce development and more about various forms of thinking and knowledge. The idea seems to be that if we develop individuals in a broad sense, then that will spill over into workforce skills and productivity. While I do believe that in some sense this is true, I am not sure how much this is happening or how important it actually is.

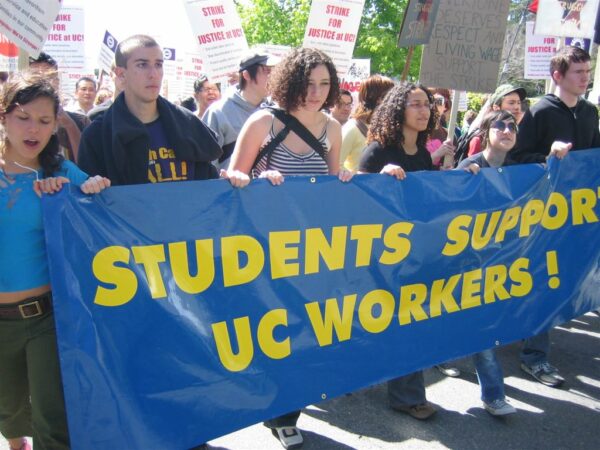

. . . The underlying structural crisis does not seem to have gone away. Indeed, in the last year and, more perspicuously in the past two weeks, it has found a more demanding as well as disquieting focus — student debt as well as the economic albatross of the maturing millennial generation itself. . . . The real scandal is the monstrous moral hazard that the student loan lending system has spawned. It amounts, according to Taibbi, “a shameful and oppressive outrage that for years now has been systematically perpetrated against a generation of young adults.”

Despite the unending political chatter over global spying, the recent government shutdown, and now the misadventure of the Obama care rollout, I have also been pondering the meaning of something worth more obsessing about. . . . It amounts to the latest variation not of Murphy’s Law (“if something can go wrong, it will”), but what I have called Raschke’s Rule (“if you didn’t think people could be more foolish than they already are, just wait a day or so”).

During the late 1920s, as the world economy careened headlong toward an economic disaster that would soon befall it, a group of European thinkers and critics steeped in both German idealism and Marxist activism converged on Frankfurt, Germany to provide identity and notoriety for the recently established Institute for Social Research at the university there.

Within time, the assemblage of now famous philosophers and cultural theorists associated with the institute, such as Juergen Habermas, Max Horkheimer, Walter Benjamin, Herbert Marcuse, and Erich Fromm, came to be known as the Frankfurter Schule (“Frankfurt School”).