…I still seek to introduce the students, now grads, to the range of political formulations in Islam, but in contrast to the undergraduate version of the course, we also look to political theology as a method for thinking about politics. Why? And How? After all, political theology is really a product of the Christian West. Does it have applicability in other contexts?

This past week, especially in light of the Copenhagen shootings, commentary about the White House summit on combatting “extremism,” and the publication of a controversial article in the magazine The Atlantic by one of its editors on ISIS, the big question in the news right now seems to be: “do the conflicts in Middle East mean we are fighting a global ‘war of religion(s),’ or at least a war with, as well as within, Islam?”

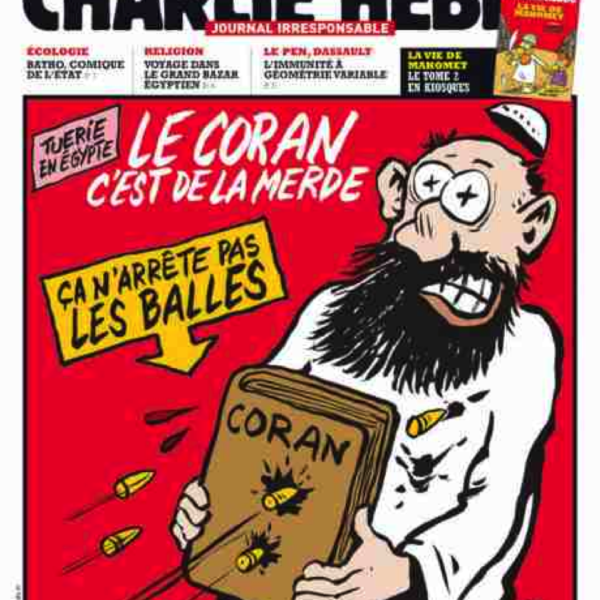

If 9/11 was the start of a moral panic in the West that the “clash of civilizations” was now underway, the tragic killings at Charlie Hebdo may have driven this panic to a new high. After all, Hebdo has a unique symbolic significance. Its satirical anti-clerical journalism represents the most valuable cultural assets of the West—freedom of speech and secularism. Moreover, Hebdo is French, and the French nation historically played a pivotal role, with its bourgeoisie revolution and laicite, in the making of Western civilization.

The proposal to proclaim the adhan or Muslim call to prayer from the top of Duke Chapel’s bell tower yesterday provoked a number of reactions. These ranged from the vitriolic and vengeful to the dismayed and discomforted. From the deluge of emails the university received and the long strings of comments posted after articles covering the issue appeared on websites, these overwhelmingly negative reactions came not just from Christians but also from Jews and those of no faith.

In the midst of the Arab uprisings, the now famous magazine Charlie Hebdo published one of their traditional satirical covers. They titled the issue “Killings in Egypt” and drew the figure of a Muslim religious activist who was riddled with bullets. The subtitle was more than eloquent: “The Koran is a piece of shit,” the agonizing Muslim was made to say, because “it does not stop bullets.”

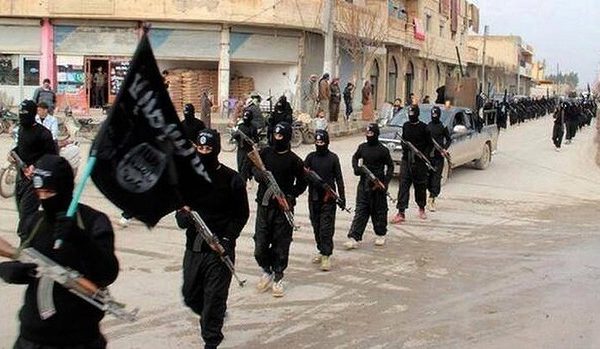

Last November, members of a Sunni militia in Syria went to a hospital, found a patient whom they took to be a Shi‘ite, and beheaded him. Showing a typical jihadi concern for public relations, they then made a video about the incident in order to get their message out, saying of the Shi‘ites: “They will come and rape the men before the women, that’s what these infidels will do. They will rape the men before the women. God make us victorious over them.” As it turned out, their video proved a bit of an embarrassment: it emerged that the man they beheaded was not in fact a Shi‘ite — but as jihadis will tell you, and not only jihadis, these things happen.

The attack of The Islamic State of Iraq and al Sham (ISIS) on Mossul and its march on Baghdad has taken the international community by surprise and raised the possibility of another US intervention in Iraq, with the hope it could prevent the downfall of the country into a sectarian war. Such a scenario is highly improbable because of the nature of the Iraq crisis that is first and foremost political and not religious.