Earlier this week, two prominent Catholic political bloggers, Elizabeth Stoker Bruenig and Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry (better known as Pegobry, or just PEG), engaged in a short but sharp exchange on the subject of property rights (see here, here, here, and here). There is not space here for a full discussion (see a longer version of this post here if you are interested in more), but I will seek to add some insight from Thomas Aquinas, who has perhaps done more than anyone to inform the Catholic Church’s reflection on these issues.

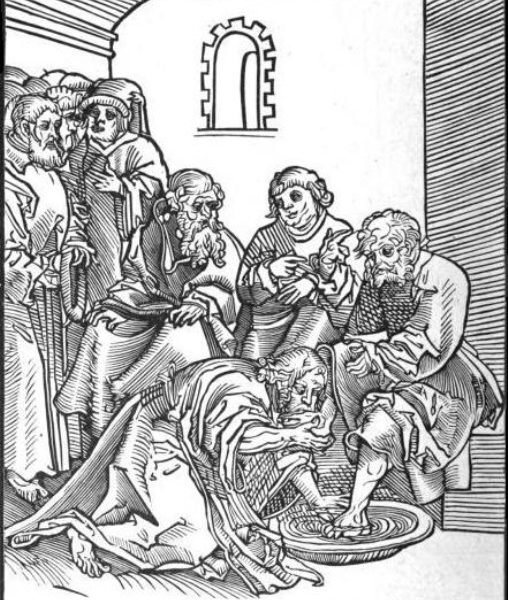

Christ’s actions on Maundy Thursday present a challenge to Enlightenment views of property. Through the Eucharistic vision of Christianity, we become more like Christ, and we do so together enveloped in an all-encompassing commandment of love: we grow together, not only in that we all simultaneously grow, but the barriers between us dissolve and our original love is mended.

As on so many issues that divide left-wing and right-wing Christians, the Bible seems frustratingly pliable when it comes to the issue of property rights. Conservative Christians like to assert that the Bible takes private property for granted, that the Eighth Commandment demonstrates it to be a “divine institution” or a “sacred right,” and that the many examples of wealthy patriarchs prove not only private property, but large accumulations of it, have divine sanction. Those more inclined toward some kind of Christian socialism like to point out Jesus’s very harsh strictures on the accumulation of wealth and the assertion of private property rights, and the early Jerusalem community’s practice of “having all things in common.” As so often happens, we seem to be faced with something of an Old Testament/New Testament divide, in which the Old Testament bolsters a conservative agenda, and the New Testament a liberal one. Is the Bible thus divided against itself?

The scathing criticisms of private property that we find in the mouth of Jesus are well-known. “Go, sell what you have,” he tells the rich man who asks for the secret of eternal life (Mark 10:21; Matthew 19:21; see also Luke 12:33). Again and again, we encounter the polemic against property, the possession of which is regarded as an evil and as a massive hindrance to joining the kingdom of God. Jesus valorises simplicity over luxury and forgoes the influence and power that comes with wealth. In short, everything about him stands against the deep values of the Hellenistic propertied classes. In the words of G.E.M. de Ste. Croix, “I am tempted to say that in this respect the opinions of Jesus were nearer to those of Bertholt Brecht than to those held by some of the Fathers of the Church and by some Christians today” (Ste. Croix 1981: 433).

I am less interested here in the twisting and turning by later exegetes to ameliorate these embarrassing texts, and my concern for now is not the Christian communist tradition that finds inspiration in these and other texts (Acts 2:44-5; 4:32-5). Instead, I suggest that this implacable opposition to property has a far deeper reason. Simply put, the very definition of private property, invented by the Romans a little over a century before the time of Jesus, is based upon slavery. That is, private property relies on the reduction of one human being to the status of thing (res) that is “owned” by another human being. Let me explain…..