In my book, The Right of the Protestant Left (Palgrave, 2012), I tried to restore Niebuhr to his precarious place within what I called the “old ecumenical Protestant left.” The reality is, the more Niebuhr’s celebrity rose among those outside of the church, the more marginal I found that he became to the main currents of liberal American Protestantism. I’m not referring here to the pacifist circles that Niebuhr turned his prophetic pen on. Rather, his friends, colleagues, and younger brother were so frustrated by Niebuhr’s indifference toward building a inter-Protestant world community—their chief interest—that they even considered leaving him out of their project altogether. Niebuhr was eventually reconciled to the ecumenical movement by his critique of “secularism” and his analyses of national and world problems through the lens of “original sin.” Still, those closest to Niebuhr continued to deride him as the “sackcloth and ashes man,” the “sin-snooping” saint who was fundamentally out of touch with the Christian hope….

In our last post, we noted that Barack Obama was the willing victim of a particularly delicious moment of irony. The very framework that has given sophistication and moral purpose to his governing – a Niebuhrian Christian realism – could cost him the 2012 election. While Christian realism allows a statesmanlike distance between the goals that can actually be achieved and the pretensions to virtue and excellence that may be desired, very few in the American electorate wish to hear about that. In other words, to win American elections, one must be a cheerleader, or a political evangelist.

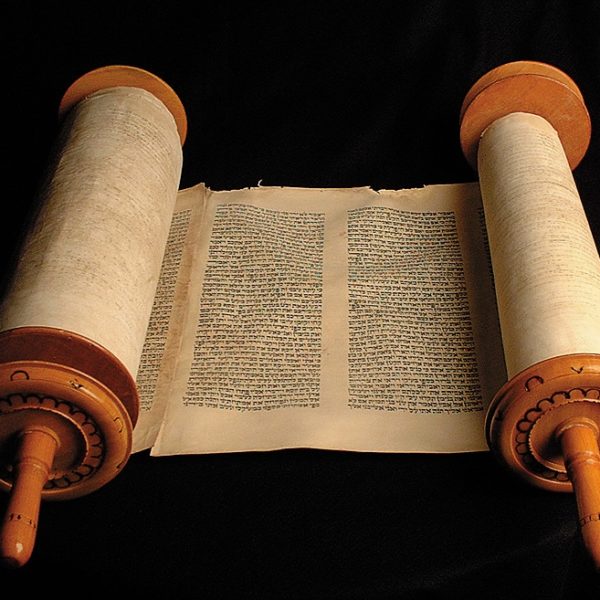

Samuel speaks of God as working in and through the events to deliver “ruin on Absalom.” This is not simply God with us. It is God against us–whenever we treat our “kingdom” as if it was ours and ours alone. Both David and Absalom acted as if their people, the Kingdom of Israel, were their own plaything.

We face a seductive fantasy of independence from a wider, dynamic order of things, with the result that our response to challenges in international relations or ecological crisis have been rather consistently out of touch. But of course this is far from simply an American problem. I suggest that it stems from a disease of the modern subject, a way of looking at the world that treats “its” objects as inert and easily manipulated. In other words, this is a deeply-rooted metaphysical problem, a constitutional failure to account for the capacity of objects in the world to push back…..

The Republic of Grace means to offer an extended account of why and how we, Christians and non-Christians alike, must learn to understand ourselves as continually, graciously, coming to be re-habituated, and recalibrated, into the grammar and language of love, even–and perhaps ultimately–in the public realm.

If my diagnosis of the situation above is apt, it seems that Christian participation in domestic politics today may also be a matter for deferred repentance.