Richard Davis

Dr. Richard A. Davis is Senior Lecturer in Theology and Ethics at the Pacific Theological College in Suva, Fiji Islands. He tweets on @rad_1968.Essays

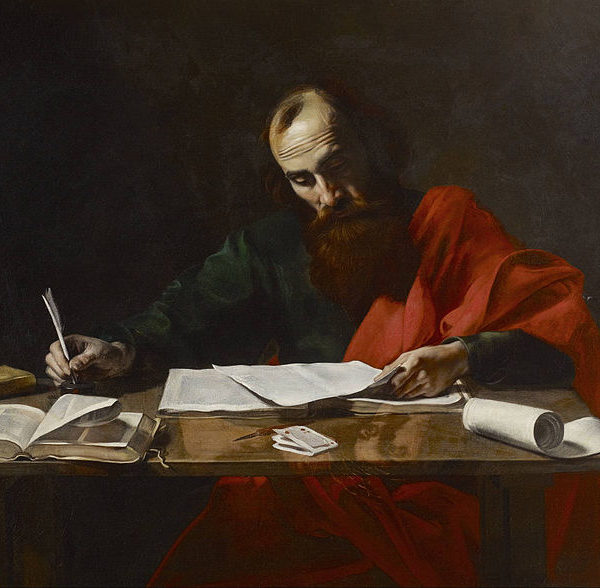

In Romans, Paul speaks of a God of reconciliation, who makes friends of enemies. Principles of reconciliation and of the love of enemies have often been quarantined from the political realm in systems of political thought that prioritize the enemy-friend polarity. However, a politics of love for enemies and of reconciliation with a creation from which we have become alienated may never have been more urgent.

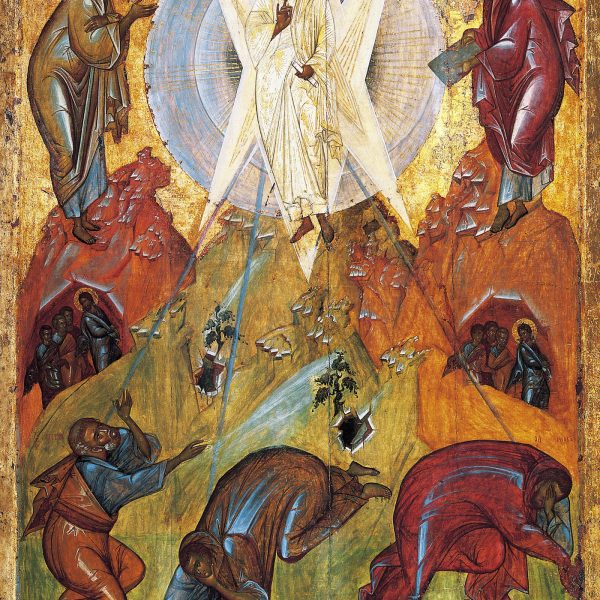

Framed merely as a story about the call to discipleship, and omitting verses 17-18, the fact that God is instigating political coups through his prophets in this passage could easily be missed if we didn’t consider the scriptural context of this week’s lectionary reading. Reflecting upon this passage and the ensuing events, we can learn something about God’s relationship to political rule.

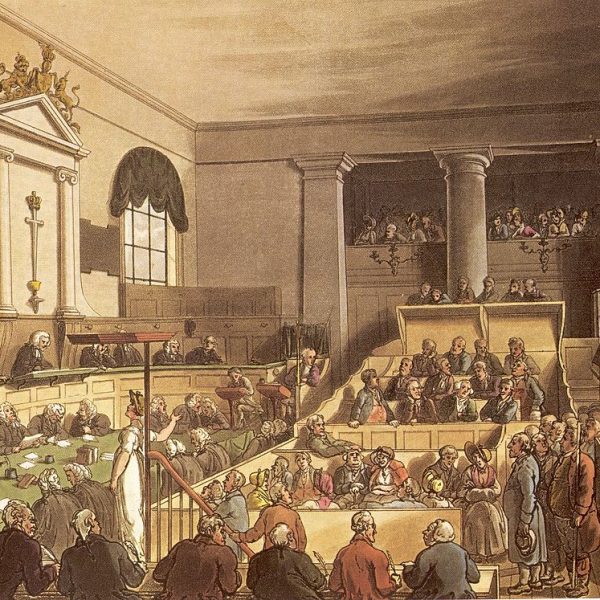

Wisdom’s publicly raised voice challenges the simple ones, who love being simple; the scoffers, who delight in their scoffing; and the fools, who hate knowledge. The reproof of Wisdom is especially relevant in the contemporary political world, where so many of our leaders and politicians thrive upon such popular attitudes.

The psalmist calls us to the fear of the Lord, offering us the secret to its pursuit. Straightforward though it may be, the psalm’s challenge to avoid evil-speaking, deceit, and to depart from wickedness and pursue peace would have seismic effects for our political landscape were we to commit ourselves to it.

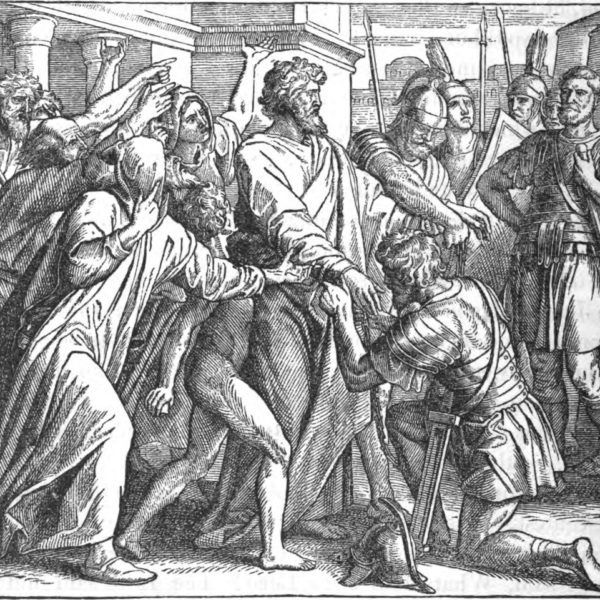

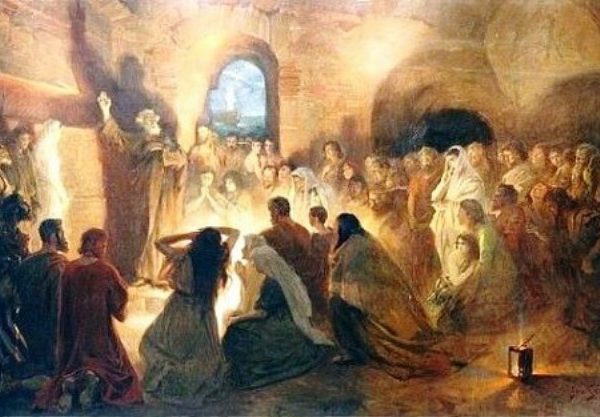

Paul’s teaching about the manner in which love for weaker brethren should guide behavior when considering eating food sacrificed to idols provides principles that remain relevant, long after the issue that provoked their articulation. The role that politics and the state play in contemporary forms of idolatry suggests analogies that can be drawn between the responsibilities of first century Corinthians and our own.

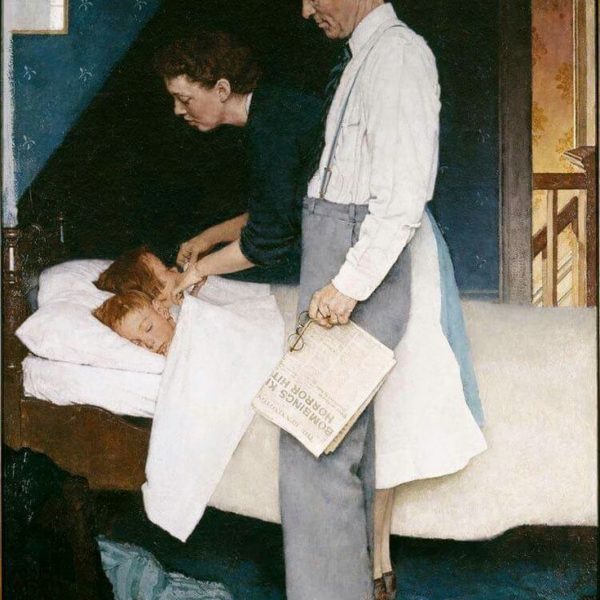

The Apostle Peter calls for the virtues of patience and peace in our waiting for the eschaton. At face value, these virtues might appear more congruent with an apolitical complacency. However, closer reflection reveals that they involve both the work of bringing peace and commitment to works of anticipation.

Paul speaks to our self-conscious understanding of tragic fatedness in Romans 7. Like him we long to be released from such an apparent fate, where we are not free to live as we know we could and should. This is more than an individual bondage to sin. It recognizes that sometimes we are prevented from living as we feel we ought by more than our own will; sometimes we are oppressed by the wills of others or even a system which seems to have a will of its own that is impermeable to reason.