I first taught this graduate seminar in 2008 as a “Topics in Political Thought” course, and called it “Political Theologies” – a political theory seminar, cross-listed with Study of Religion. Part of the motivation for teaching it was finding a set of themes and readings that would work well in a cross disciplinary way, as I’m jointly appointed to both Political Science and Study of Religion.

The John Cabot University Summer Institute for Religion and Global Politics (May 19 – June 20), co-funded by the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR), offers graduate students a comprehensive introduction to contemporary issues and debates regarding the roles of religious actors, ideas and institutions in democratic political life and international affairs.

. . . We begin with a first dip into the conceptual issues (the issues of political form, legitimacy, cosmic analogy, acclamations, secularization) by reading the third chapter of Schmitt’s Political Theology. Then we move on to show that grounding “political form” (Schmitt) by embedding it into a cosmic structure has been an issue at least from the Hellenistic period (if not before).

This May, two exciting conferences on political-theological themes have been organized to take place in Rome back-to-back. The first, “Economic Theology/Theological Economics” is taking place at Lumsa University in Rome, May 20-21.

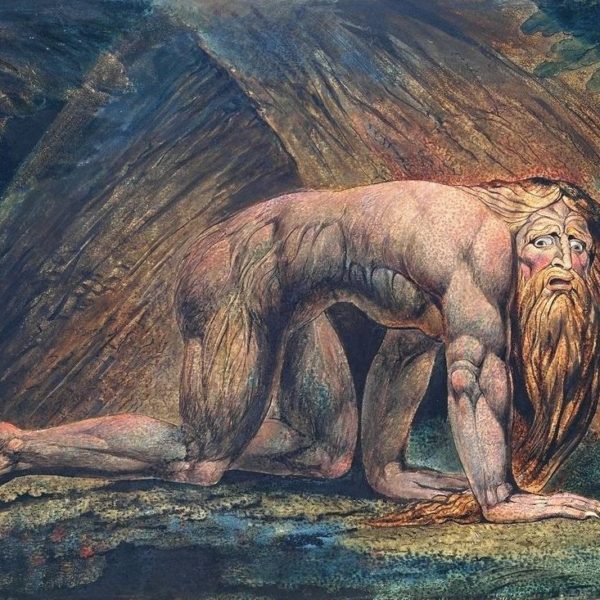

The first goal was to open up how students “read” a text, which in turn means opening up how they understand both “scripture” and religion. In that regard I consider myself a Blakean – I read the texts as poetry, most of all, but reified into “theology” and law by “priestly” types, so that, to experience those texts again we must go behind how catechisms have taught us to read them.

This issue of Political Theology focuses on the theme of “religion and radicalism.” It is one of the fruits of an international research network of the same name, a network that has members from nearly every inhabited continent on the globe.

When I was asked to contribute syllabi on political theology I thought it would be a great chance to look back and reflect on how my thinking and teaching on the topic have evolved. I think of a course I am currently teaching under this rubric, even though its title and official description eschew all reference to theology, and some of the very first courses I taught were expressly geared toward the topic of political theology.

The phrase “political theology” is used in many ways, across many disciplines. Over the past few years, an increasing number of courses have been offered calling themselves Political Theology, or describing their topics as political theology. We have invited faculty from political science, religious studies, theology, and history who teach courses on political theology to share their syllabi on this blog over the coming weeks, and to reflect on political theology pedagogy

Following the very useful list posted on Religion in American History, we’ve put together a list of several forthcoming books relevant to political theology to keep an eye out for as they are published in the coming months. If we’ve missed any, please share them in the comments. Come summer, we hope to have another list for you, introducing all the books due in the second half of the year.

Let’s be clear. There is no academic field called “Islamic Political Theology”. So naturally there are hardly any books on Islamic Political Theology. Political Theology is largely a field of study within Christian Theology. This field, as I understand it, examines the relationship between the way we describe God and the way we describe the political. In the history of the Church there has been a strange correspondence between the two. A number of shared concepts, narratives, myths and symbols sustain each.