The story of Jesus’ healing of the blind man in John 9 presents us with the politics of exclusion in operation. However, in a twist, it is the politics of exclusion that are revealed to be excluded.

The emergence of a new critical theory for the 21st century, exemplified in the writings of such theorists as Foucault, Agamben, Žižek, and Badiou as well as in such zones of contemporary discourse as biopolitics and globalization theory, has tremendous yet still uncharted consequences for theological thinking.

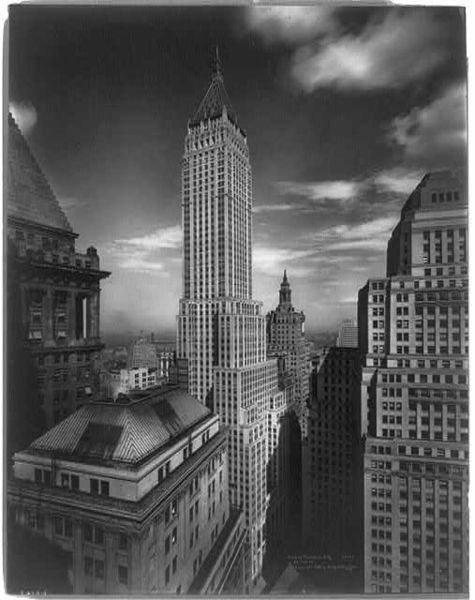

Democracy is in crisis. Or, or more significantly, liberal democracy is in crisis. So writes Philip Coggan recently in The Economist, the Western world’s foremost punditocratic commentary on the shifting social, cultural, and political terrain that goes by the slippery name of “globalization”.

There is a famous anecdote in which a man, after death, wakes up surrounded by all the pleasures of life: food, sex, and leisure. An angel approaches him and says “Welcome, enjoy all the pleasures you have ever wanted.” The man basks in all the pleasures available, but after a few weeks of uninterrupted ecstasy, he grows bored. So, the man approaches the angel and says “Is there anything I can do, any work?”

Despite the unending political chatter over global spying, the recent government shutdown, and now the misadventure of the Obama care rollout, I have also been pondering the meaning of something worth more obsessing about. . . . It amounts to the latest variation not of Murphy’s Law (“if something can go wrong, it will”), but what I have called Raschke’s Rule (“if you didn’t think people could be more foolish than they already are, just wait a day or so”).

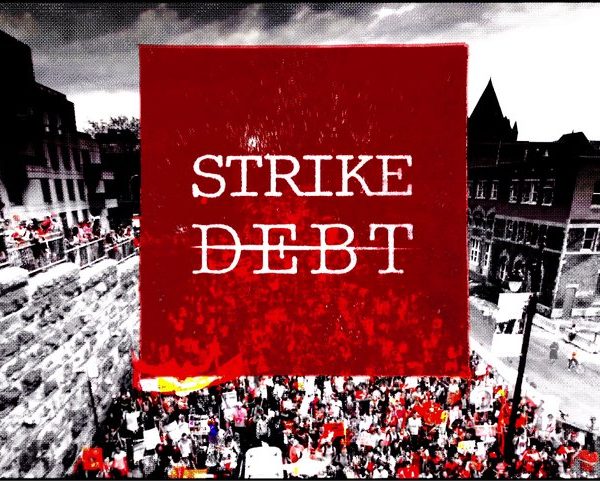

At the very least we might say that both nonviolence and pacifism should attempt to understand and redirect violence. And maybe we should shelve the tired terms for a spell and speak of life-giving or death-dealing acts, which might reframe exhausting debates about property destruction. Pacifism should not be at odds with physical force, with the force of physicality such as sit-ins, strikes, human chains, roadblocks, or even strategic property destruction.

It’s become something of a commonplace among commentators and critics on both ends of the political spectrum to declare the death of the Occupy movement, whose campaigns against social and economic injustice and political corruption began to garner international attention in mid-2011. Although the last of the movement’s higher profile encampments were shut down in early 2012, it would be a mistake to conclude that Occupy is no more.

Nonviolence and pacifism are often pitted against one another, even though pacifism was once considered the activist term to distinguish it from nonresistance. Now, pacifism is thrown under the bus, even by vigorous advocates of nonviolence. For instance, Gene Sharp clarifies that nonviolent action is, appropriately, action that is nonviolent, as opposed to pacifism.

Here’s a brain-teaser for you. How does a recent PBS documentary about America’s “Dust Bowl” of the 1930s combine with a just-published book by one of the nation’s best-known venture capitalists to shed light in an unprecedented and powerful way on the government shutdown and the struggle over the debt-limit?

In 2008, I worked in Ramallah as a journalist and interim editor for the Palestine Monitor, a web-based news source committed to “exposing life under occupation.” I traveled throughout the West Bank, writing several articles about the village of Ni’lin, whose olive groves and roads are fractured due to the construction of the separation wall.

Apparently, nonviolence and democracy are strongly connected. Recent research suggests that nonviolent resistance campaigns are much more likely than violent ones to pave the way for “democratic regimes.” . . . But what, in the world, is democracy? The term resides in a restless spectrum, so perhaps the adjective democratic should be employed more than the noun.

Over the last 6-7 years, a growing body of literature has coalesced around the idea of just intelligence theory. The burgeoning interest has resulted in the establishment of the International Intelligence Ethics Association, as well as the attendant International Journal of Intelligence Ethics. As a sub-specialty of intelligence ethics, its aim has been to integrate just war theory with intelligence collection, national security policing and domestic counterterrorism – subjects that fall in a murky “middle ground” between external and internal opponents.