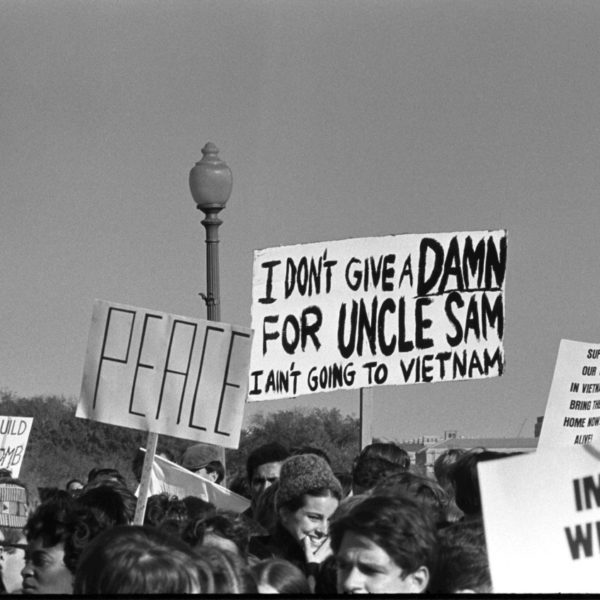

When we understand that the Nixon campaign combined a call to law and order with the so-called Southern Strategy, it becomes clear that white sympathies were cultivated and that blacks were made to play the part of the enemy. Nixon’s presidency was a take-no-prisoners form of democracy mixed with demagoguery.