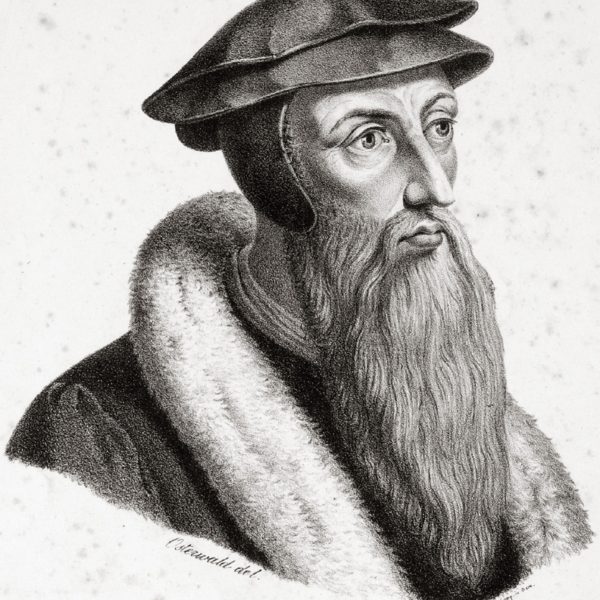

One of the great paradoxes of John Calvin’s political theology can be captured in terms of two of the phrases the reformer used over and over throughout his writings. On the one hand, he emphasized, “the kingdom of Christ is spiritual.” On the other hand, through the kingdom of Christ God is bringing about the “restoration of the world.”

. . . Here, I focus on Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theology of friendship. My underlying proposal is that Bonhoeffer’s particular approach to friendship which emphasizes concrete, personal encounter with “the other” in community is uniquely suitable for Christians in an increasingly pluralistic, politically polarized, and techno-social world. My hope is that Bonhoeffers theology and praxis can challenge us to think more deeply and comprehensively about what is required for Christian witness in the 21st century.

Is the Taiping Revolution (1850-1864) the moment when the revolutionary Christian tradition arrives in China? I suggest that it is precisely such a moment, for a number of reasons. These include a radical reinterpretation of the Bible, a thorough challenge to the underlying structures of existing power, a communistic way of life, and the development of a distinctly new religious form.

The Middle Ages were filled with strange, passionate, and fascinating figures, often hidden from our view by the long shadows of the likes of Anselm, Francis, Aquinas, or Ockham. The great theologians earned their influence, of course, but there are also things to learn from some of those to whom history has been less magnanimous. I want to introduce one such figure here: Arnold of Brescia.

This is the fourth, and final, post in a series that was kick-started last September with a short discussion of how the growing field of just intelligence theory might be overly influenced by jus contra bellum thinking, or what Tobias Winright has coined “the presumption against harm version of just war theory.” This particular variant of just war theory is defined at its core by a presumption against war or a presumption against the use of force.

In the first volume of Capital, Marx writes: ‘Englishmen, always well up in the Bible, knew well enough that man, unless by elective grace a capitalist, or landlord, or sinecurist, is commanded to eat his bread in the sweat of his brow, but they did not know that he had to eat daily in his bread a certain quantity of human perspiration mixed with the discharge of abscesses, cobwebs, dead black-beetles, and putrid German yeast, without counting alum, sand, and other agreeable mineral ingredients’.

Foucault’s emphasis on the ‘care of the self’ is usually hailed as a significant challenge to the understanding of ethics. With the tendency of ethics to focus on the ‘other’ and how one relates to that other, the turn to consider the construction of the subject seems to be radical. This was also Foucault’s answer to the perennial problems of ethics . . .

….Because war’s constituent ingredients are killing and/or physical harm, and because, in Childress’ argument, those two things are “intrinsically prima facie wrong” because of the prima facie obligation of nonmaleficence, war itself is prima facie wrong. Therefore, for Childress – and those who follow him – just war theory has evolved out of the need to justify the overriding of nonmaleficence but begins with the presupposition of war’s prima facie wrongness.

In a sermon on 1 Tim 6:1-2, John Calvin commented,

“…but they were slaves, of the kind that are still used in some countries, in that after a man was bought the latter would spend his entire life in subjection, to the extent that he might be treated most roughly and harshly: something which cannot be done amidst the humanity which we keep amongst ourselves. Now it is true that we must praise God for having banished such a very cruel brand of servitude.”[1]

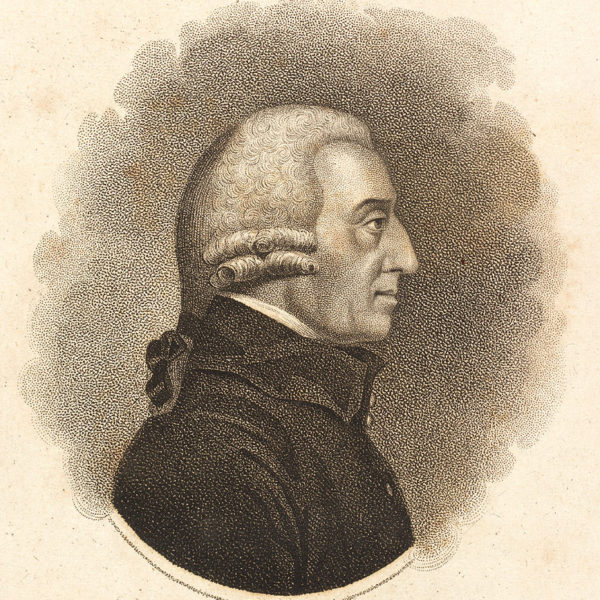

Adam Smith’s skill was as a storyteller of the first order. It takes one a while to realize where his appeal lies. As many have noted, his Wealth of Nations is rambling, polemical, and rather cavalier with evidence. All this sits rather strangely with the popularity of his writing, both then and now. How to understand that appeal? We suggest it may be found not in any skill at constructing careful and detailed argument, but in his ability to tell stories.

In likening kingdoms lacking justice to criminal syndicates, Augustine invokes the story of a confrontation between Alexander the Great and a pirate. Indeed, Augustine judges “that was an apt and true reply which was given to Alexander the Great by a pirate who had been seized. For when that king had asked the man what he meant by keeping hostile possession of the sea, he answered with bold pride, ‘What thou meanest by seizing the whole earth; but because I do it with a petty ship, I am called a robber, whilst thou who dost it with a great fleet art styled emperor’” (De civ. Dei 4.4.1).