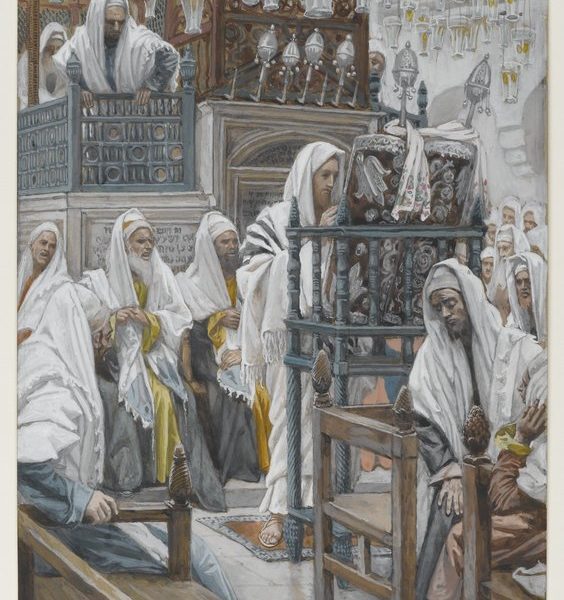

In this week’s reading from Mark’s gospel Jesus challenges the complacency that so commonly comes with privilege. The ease of privilege within the status quo can inure us to the claims of truth or justice that might unsettle it or that might trouble its assurance of its purchase upon reality. Yet such claims lie at the very heart of the Kingdom of God.

The storm at sea is one of the most potent experiences and images of chaos. Jesus’ miraculous calming of the storm is an image, not merely of his power with regard to nature, but also of his mastery over the chaotic political elements that threaten us.

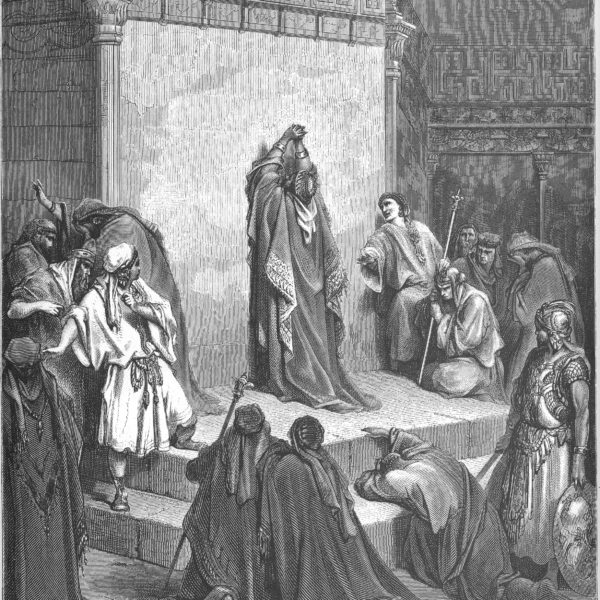

The biblical images of God as divine king are often handled with embarrassment in a more egalitarian age. However, although it may appear little more than accommodation to ancient despotic assumptions, throughout the Scriptures the kingship of God is presented as a great force for liberation against all human tyrants.