The story of the encounter of Saul of Tarsus with the risen Christ on the road to Damascus is read in a number of differing ways, readings often shaped by what the church has become for us. At our juncture in the developing history of ‘The Way’ we have the opportunity to explore a different vantage point on this story, one shorn of much of the triumphalism of past readings and tempered by our uncertain times.

In most reflections about Good Friday and the events surrounding the Passion, the focus is squarely on Jesus, and to be sure, one can hardly deny that this is where it should be. However, it is interesting to note the extent to which the Gospel authors are quite interested in what these events reveal about the disciples that had followed Jesus up to this climactic point in his ministry—not just the Twelve, of course, but all those who had heard his word and believed in him.

Christ’s actions on Maundy Thursday present a challenge to Enlightenment views of property. Through the Eucharistic vision of Christianity, we become more like Christ, and we do so together enveloped in an all-encompassing commandment of love: we grow together, not only in that we all simultaneously grow, but the barriers between us dissolve and our original love is mended.

The encounter of Mary Magdalene with the risen Christ provides us with a model for understanding political theology. The elusive presence of the resurrected one and the emptiness of his tomb forbid all our attempts to secure his presence in our praxis and open up new ways of perceiving our social task.

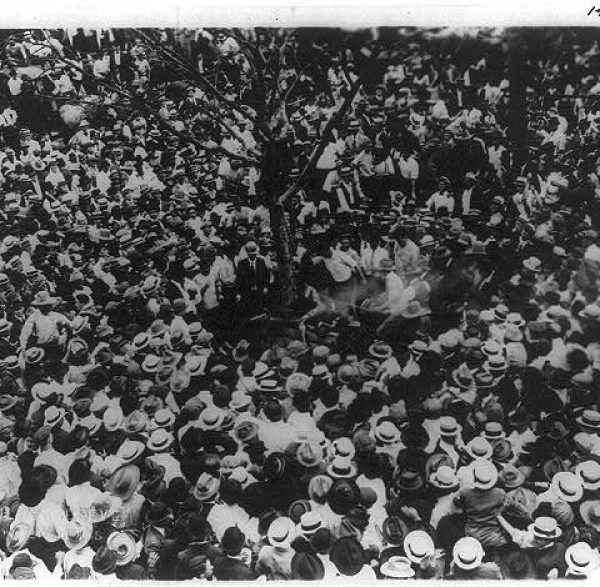

The contagious violence of a frenzied mob brings about the sentencing of Jesus to crucifixion by Pilate. The operations of the scapegoat mechanism are revealed in the record of these events and, as we reflect upon them, we will learn to identify its operations within our political life. In Christ we find an alternative model for desire, which can enable us to resist the seduction of unity through violence.

This may seem an odd pairing – Secularism and Political Theology – but in a way that I can’t quite articulate, they still seem to go well together, beyond being two important recent topics that weren’t yet covered by the course offerings in my department.

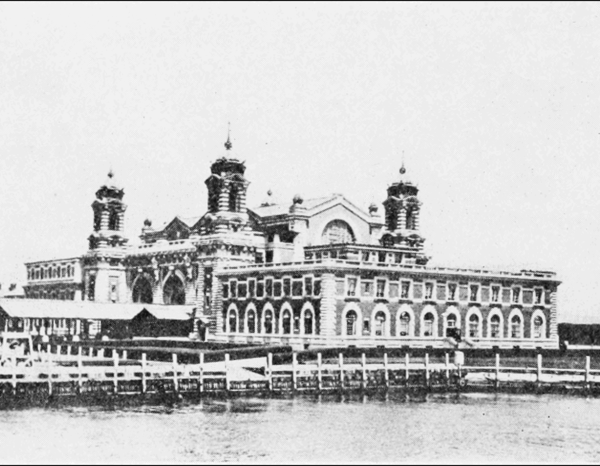

The first reaction of the reader to Abram’s calling, “That’s supposed to be me,” gives way to the second realization, which is “That COULD be me.” And it is in imagining the fear and anxiety normally attendant to leaving everyone and everything behind that the seed is planted in the reader’s heart for concern for real-life strangers.

Although at first glance they may appear incidental, the frequency of border crossings in the story of the raising of Lazarus suggests the presence of a theme. Through a narrative of successive boundary crossings, the power and willingness of God to traverse any distance and border is made manifest.