August 28th 2013, reminded us of the power of the spoken word as the world commemorated the 50th anniversary of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr’s historic “I Have a Dream” speech. What was celebrated was the moral power of words to transform history – this despite the risk and tragedy of empty rhetoric which has inundated it.

Being a pacifist and an American is virtually impossible. Typically, the peace and justice community focus on violence issues, human trafficking, and other visible forms of oppression. They come out against war and unsanctioned military engagement (which is basically the status quo in the global capitalist empire: instead of war, we have police action). All of these things are unjust and need to be opposed, but ultimately they are the blood dripping from wound that we keep wiping up without recognizing their source: global capitalism.

The prophet Isaiah was a city dweller, but his mind was on the countryside. Trees, vineyards, and fields populate his thinking and that of his successors in this long book, where vegetation serves both as metaphor (as in Isaiah 5:1-7), and as the life-sustaining growth on which humans literally depend (as in vv. 8-10). Agricultural imagery appears from one end of the book to the other (1:8; 66:17), spelling out both judgment and hope.

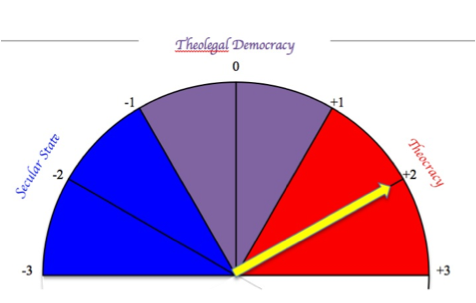

The United States is comprised of a religiously diverse citizenry, which leaves officials to balance the tension upheld by a constitution that simultaneously prevents the establishment of a national creed and yet preserves one’s right to freedom of religion. In practice, officials in the United States cannot legislate theology, but they can, and do, use theology to legislate.

As a result, the United States is not a secular democracy where laws guarantee freedom from religion and dismiss theological rhetoric in the political process; neither is it a theocracy, where a single religion prescribes all laws. Whether we like it or not the United States is a theolegal democracy.

Personally, I’m glad that Hosea is in the lectionary, though there is not much in it that we will “like.” As it is with spinach and colonoscopies, we can nonetheless grasp the value of things which otherwise might leave us cold.

Last week I sat supping tea, on a glorious summer’s day, in a garden with one of my favourite people in the world. My friend raised one of those questions about women as bishops which is not usually part of the narrative (certainly among those of us who treat this matter as urgent): Why on earth do women want to be bishops anyway? Her question was not prompted by any anxiety about women’s ministry or place within the church. Rather her question was prompted by concern about how bishops are ‘seen’ in the C of E, that is, about how clergy and laity behave around bishops.