The Infinite Love of Pope Francis

By James Padilioni, Jr.

Like Shannen Dee Williams, the 1992 comedy Sister Act represents a watershed moment in the formation of my childhood Catholicism (Williams 2022:17). In the finale scene, the choir of nuns under the direction of Sister Mary Clarence (played by Whoopi Goldberg) sings their sanctified rendition of “I Will Follow Him.” The camera pans over the choir loft, rising above the pews of the sanctuary, packed full with worshippers, until it finally came to a perch at the back of the balcony, revealing that (a stunt double who looked like) Pope Saint John Paul II, himself, was in attendance. One day while watching this scene as a child of 7 or 8 years old, the same period of life during which I underwent the sacraments of Reconciliation and First Communion, I remember feeling overcome at the mere cinematic suggestion that one might see the Pope in person, prompting what I can only describe now as a near-ecstatic experience, as I struggled to fathom the full significance of the Pope’s divine regality as the Vicar of Christ.

Fast forward nearly 20 years to the summer of 2013, just a few months after Pope Francis had assumed the throne of the Holy See. I was traveling through Italy and France as part of the first archival trip pertaining to my dissertation. In the several months leading up to this summer, I began discerning whether to situate my research squarely within Black Catholic Studies, or if I wanted to focus more broadly on Black Diasporic performance traditions. I had 36 hours to see as much of the Eternal City as I could before continuing northward to a cultural studies conference hosted at the Umbra Institute in Perugia (incidentally, the ancestral home of the Padiglioni Family, who I met during this trip for the first time). Guided by a Roman friend, we embarked on a flash tour of the city, but we lost track of time, and arrived at the Vatican too late to join the final tour of St. Peter’s Basilica that departs at 4pm, but the Swiss guard informed us we could linger in the Square for as long as we wanted. Disappointment swelled in my chest – had I truly come all the way to Rome to miss seeing inside the Vatican by 15 minutes? To console myself, I tried to downplay the significance of what I missed, thinking to myself, it’s ok, it’s not like I’m still the child version of myself, little Jimmy would have loved this though. I wish I could time travel him here instead of adult-me.

Among paranormal investigators, the “hitchhiker effect” names those occurrences when a supernatural entity seems to attach itself to an investigator and follow them home from the site of their initial encounter. I realize now that I experienced a version of this following the Vatican visit. Though I had adopted a fashionable air of agnosticism amongst my peer group from university, I visited the Vatican in 2013 because I was drawn to Papa Francesco in a secular sense, and the more I dug into his South American liberationist-adjacent worldview, it attuned my scholarly research focus to that first liberationist from South America, St. Martin de Porres (1579-1639). Like a hitchhiker, I credit the transformative power of Pope Francis’ love for latching onto this lapsed Catholic’s heart. And as I’ve written on this blog previously, I have eagerly looked to Pope Francis’ vibrant vision for a flourishing planetary future as part of the Laudato Si’ Movement, a global mobilization of the Church in response to Pope Francis’ poignant question: “the world sings of an Infinite Love: how can we fail to care for it?”

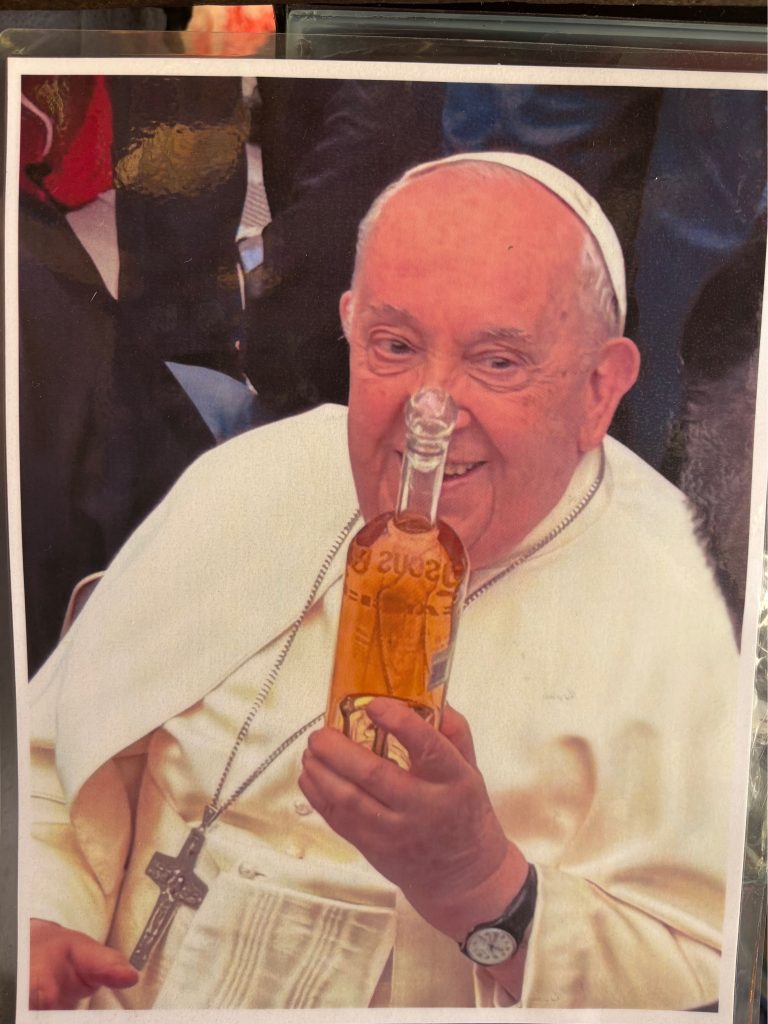

Fast forward once more to July 2024, during a visit to the appropriately-named town of Todos Santos (All Saints), located at the southern end of Baja California. I sat down for a tequila tasting, and, after several sips, I spied a photo of a smiling, beaming Pope Francis hanging behind the bar, documenting the moment when a group of Mexican pilgrims visiting the Vatican gifted Papa Francisco with a hand blown glass bottle of Nueva Era tequila añejo, which he received with great delight.

With this photo, I digitally libate Pope Francis’ holy memory. May his boundless joy, his love for God’s flock, and his deep wellspring of humanity forever be the strongest intoxicant one can imbibe and share with others.

When a Pope dies, another one is made

By Valentina Napolitano

Yes and no.

The passing of Pope Francis caught many of us by surprise. Not because his death was unexpected—his frailty in recent months signaled that he stood at the threshold between life and death—but because of how he went: on Easter Monday, the day of Lazarus the resurrected, after blessing a crowd, delivering an address, offering commitment, and calling for awakening against a long string of wars and the mindset of war as something to resist. It was uncanny. Uncanny, in the Freudian sense, when something is too familiar, too close, and therefore jarring. The uncanniness lies in the force of the leader’s deep truthfulness, his profound mattering in the here and now—and then he was gone.

Francis has been a complex figure—the first Jesuit pope, and Latin American pope. The Company of Jesus (the full name of the Jesuit order) is itself complex. Founded in the early 16th century, the Jesuits were founded as “warriors of the Pope,” a Company forged with a deep sense of solidarity and also readiness to be alone in the world, on a mission for the Church and the Pope.

Francis was on a mission—at the center of the Holy See, more commonly known as the Vatican. Over thirteen years, his pontificate unfolded as a reversal of the centripetal forces of the Church. That is, he relocated the immobile motor of the Church—the heart—not just to the periphery, to those far from power, to those seen as marginal in the literal sense, but through a new dynamic of centrifugal and centripetal movement: learning and being moved from the outside (the periphery) in (toward the center of the Curia Romana)—not from the long existing movement inside out. Francis placed the passionate heart of the Church not at the center, but in the centrifugal force of the margins coming back to its institutional center. That is a pretty ‘geo-seismic’ revolution.

Francis challenged the Church’s attachment to the reproduction of clerical power – the problem of clericalism. We can, indeed, trace the co-emergence of global Christianity and global capitalism, particularly through colonialism and slavery. The Jesuits themselves have recently undergone a reckoning with their historical entanglements with slavery in the Caribbean and the so-called New World. And Francis stood against allowing the invisible hand of the Church—financially and evangelically—to mirror the invisible hand of the capitalist market.

This papacy has been historically momentous. Raymond Williams, the British literary critic, reminded us that cultural transformation involves a mix of what is emerging and what is receding. Francis has been a charismatic figure standing precisely in this space between the disappearing and the emerging. He offered tenderness and embrace, a focus on encountering people on their ground, and on the ethical significance of individual relations—while also holding firm private command over the Vatican’s machinery. If Benedict XVI was a theologian’s pope—intellectual, and to certain extent remote—Francis was radically different: a “gentle” Jesuit warrior. He brought intimacy to leadership, and yet remained forceful—some say even stubborn—in private mastery.

Importantly, he was a person of the people—but not a populist. That distinction is one of his great strengths, and perhaps one of his great challenges. He connected with the periphery, but resisted the antagonistic crowd dynamics that define much of today’s populist leadership. He addressed capitalism’s inability to truly see. He named the globalization of indifference and called for a refusal of a system that doesn’t just waste things—it wastes people. In Catholic thought, not seeing is a sin: acedia, spiritual sloth. The body that can’t stay awake—like medieval monks who dozed off while transcribing sacred texts—fails to engage in the act of spiritual care. These texts were often the most prized possessions of monasteries and noble houses.

Francis called us all—Catholics and non-Catholics—to awaken. To take a stand. To care for our common home. To step beyond the religious/secular divide. He embodied a charisma of presence, not domination. He drew people close, yet each one never lost their own path of discernment—the Jesuit mode of always dialoguing with God in a process of discernment, yet never being alone—always feeling they were in the “Company of.”

What does it mean to be in the Company of Jesus—not in a brotherhood? It means to be co-responsible. To discern what it means to live in common. To be present without being swallowed by the crowd. Populist crowds are often animated by antagonism or disillusionment with the state—by being with and as intimate strangers. The crowds Francis foregrounded were something else: people in the company of each other. Attentive to those made marginal, and able to see marginality as central— a future in the present.

If the linguistic root of economy means the management of the household, then Francis, evangelically, insisted that migration is not just a humanitarian concern—it is intrinsic to the management of the world as our home. He affirmed both the right to move and the right to stay. He called us to a world that already exists, but to which we have yet to take full responsibility.

And that responsibility is not for others. It is with others.

Even so, Francis faced limits. There were contradictions he could not—and did not want to—resolve, including the much-needed opening of deaconate/priesthood for women and a more nuanced, encompassing position on abortion and end-of-life care. Yet some felt his stance on the latter was not decisive enough. Disenchantment persisted, especially among parts of the Church more deeply invested in mystery, in hierarchy, in the figure of the Pope as removed thus perceived as sacred. Watchers of The Young Pope, the HBO series starring Jude Law and directed by Paolo Sorrentino, may understand the appeal of a different model: a pope who exercises power through kenosis, divine withdrawal—a presence made visible by absence. Some of Francis most vocal detractors are drawn to this theological force. They seek a pope whose mystery and power lies in his distance, not his nearness.

A new pope will be made. Catholics or not, he will face the task of embodying a charisma of a Church rooted in profound discernment—of being in company with others in and for our common home—while also moved by the mystery and power of a presence revealed through withdrawal. Not an easy task indeed.

Share This

Share this post with your friends!