The journal Political Theology is very pleased to announce the addition of seven new members of its Editorial Board. These distinguished scholars further broaden the journal’s reach and scope. They include scholars of political theory, philosophy, law, anthropology, and theology, with expertise in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, based in the United States, Brazil, Israel, France, and India. They join a vibrant group of current editorial board members that includes Cornel West, Miroslav Volf, Judith Butler, and Rowan Williams. Here are the new board members:

Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem, his trial, suffering, death, and resurrection, bring into full circle his journey to Jerusalem that was not shaped by Herod’s murderous threat but by his redemptive obedience to God’s will.

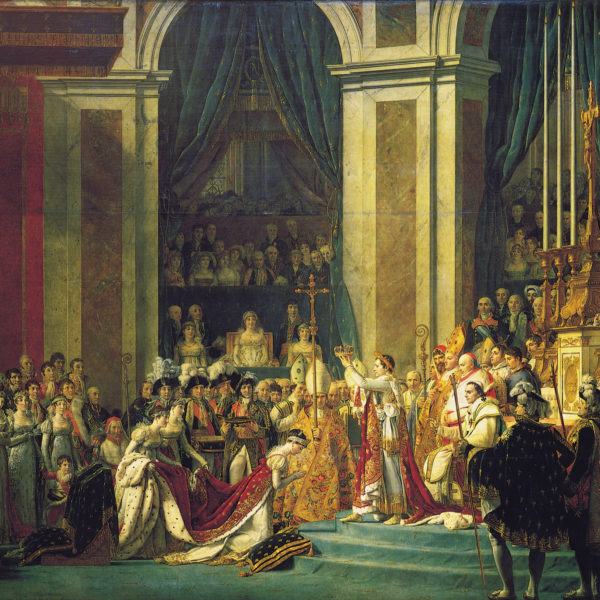

Spectacle has always played an important role in establishing power, authority, and sovereignty. In the unity of the dazzling body of the Transfiguration and the brutalized body of the crucifixion, the integrity of the spectacle and that which lies beneath is made known and our own polities’ lack of such integrity is challenged.

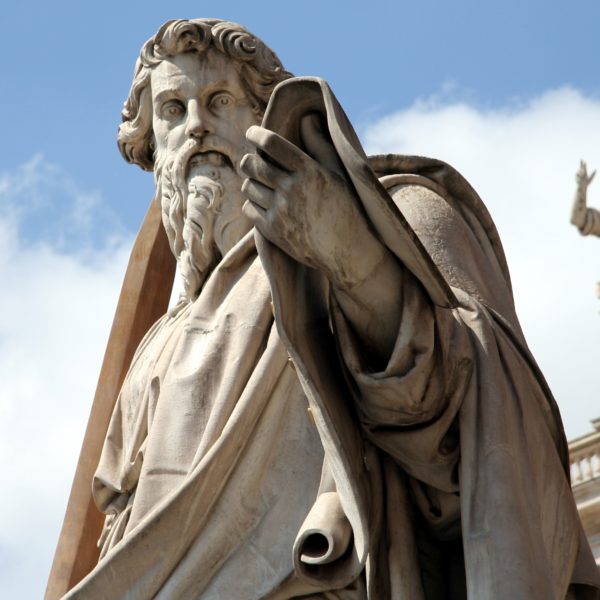

As it is often detached from its broader context and treated as a standalone paean to love, the significance of 1 Corinthians 13 within Paul’s overarching argument about the Church as a polity is often neglected. When the context of this chapter is appreciated once more, its political significance will emerge.

Paul’s vision of a social body formed around a crucified Messiah turns on their head many of the prevailing dominance models of society of his own day. The concern for members of society otherwise marginalized and devalued produced by such a political vision is one with considerable relevance to our own day.