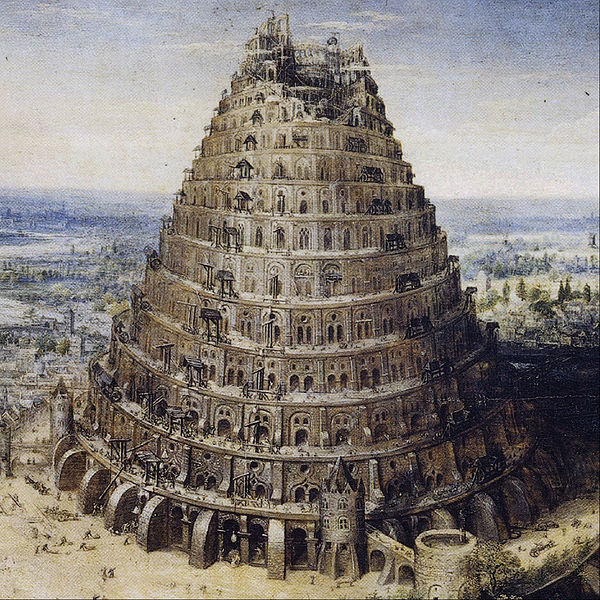

As the people of Pentecost, our political vocation is to manifest the reality of God’s worldwide kingdom, to be a place where the enmity between peoples is overcome and the many tongues of humanity freely unite in the worship of their Creator. Amidst the Babelic projects of the ages, the Church proclaims by its existence that the kingdom belongs to God, that there is no other true ruler over all the nations.

. . . Here, I focus on Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theology of friendship. My underlying proposal is that Bonhoeffer’s particular approach to friendship which emphasizes concrete, personal encounter with “the other” in community is uniquely suitable for Christians in an increasingly pluralistic, politically polarized, and techno-social world. My hope is that Bonhoeffers theology and praxis can challenge us to think more deeply and comprehensively about what is required for Christian witness in the 21st century.

The stark repetition of the admonition to being of one mind in the first and last phrases is particularly arresting, and particularly challenging for us today. After all, for contemporary liberalism, being of one mind is no virtue, and the same could be said for most contemporary Christians. We no longer think of pluralism as simply a pragmatic political strategy for negotiating irresolvable difference, but as a good in itself. It is difference, we say, that makes us strong, tolerance and indeed embrace of otherness.

The myth of Captain America introduces us to a serious quandary. Can liberal democracy be de-coupled from violence or is it doomed to repeat old battles? For Christians the question is doubtless a complex one. The Church can doubtless find much in Rogers’s democratic creed to admire; his sense of self-sacrifice, his public spirit and sense of civic duty. There is something of the righteous pagan in the Captain America myth which should not be lightly dismissed.

Is the Taiping Revolution (1850-1864) the moment when the revolutionary Christian tradition arrives in China? I suggest that it is precisely such a moment, for a number of reasons. These include a radical reinterpretation of the Bible, a thorough challenge to the underlying structures of existing power, a communistic way of life, and the development of a distinctly new religious form.

Within many criminal justice systems, deterrence is a significant element of the rationale of imprisonment. However, Paul’s letter to the Philippians reveals the emboldening power of imprisonment for faithful witness. The example set by courageous leaders who will risk imprisonment for the sake of truth and justice continues to have great power, even within our contemporary situation.

On the surface Captain American: the Winter Soldier is a cinematic triumph of patriotic romanticism. Whatever injury has been done to the American psyche in the early part of the twenty-first century, Marvel has done its best to bind these wounds and produce a tour de force of idealism for a less than idealistic age. Captain America has done for democratic virtue what the West Wing did for American government.

The international crisis in Ukraine, combined with the precipitous and aggressive behavior of Russia toward the West, the docility of Europe and the fecklessness of American foreign policy in shaping events, has prompted after-midnight calls among many international experts for a radical and rapid rethinking of what the word “globalization” really means, or what it might look like even in the next five years.