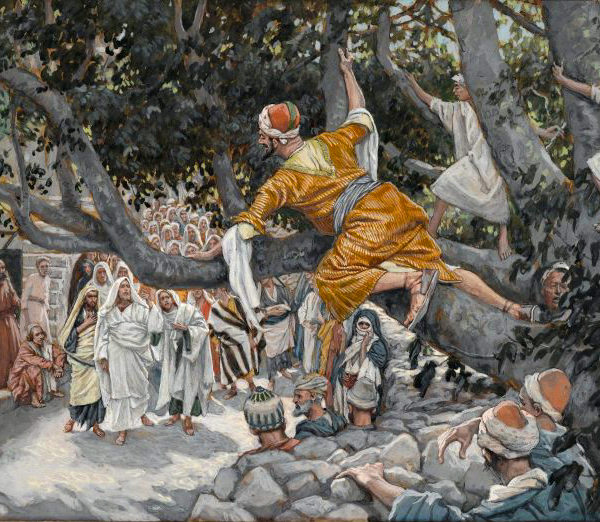

In the declamation of Isaiah 1, the prophet associates Judah and its rulers with Sodom, for their inhospitality, injustice, and the presumption that they can hide this from God. Zacchaeus, a man characterized by such Sodom-like injustice, is delivered from this as justice is welcomed into his house in the person of Jesus.

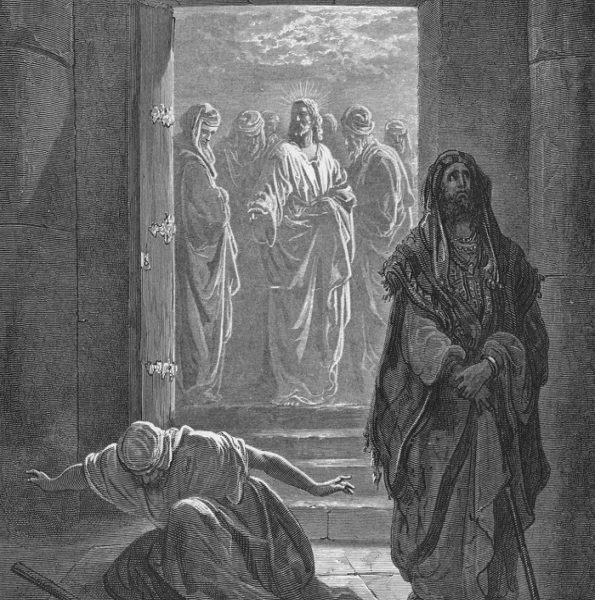

The Parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector is situated against the backdrop of the promise of the coming kingdom and the vindication of the righteous that will come with it. We too can look for future vindication and Jesus’ parable may speak to our own convictions about being on the ‘right side of history’.

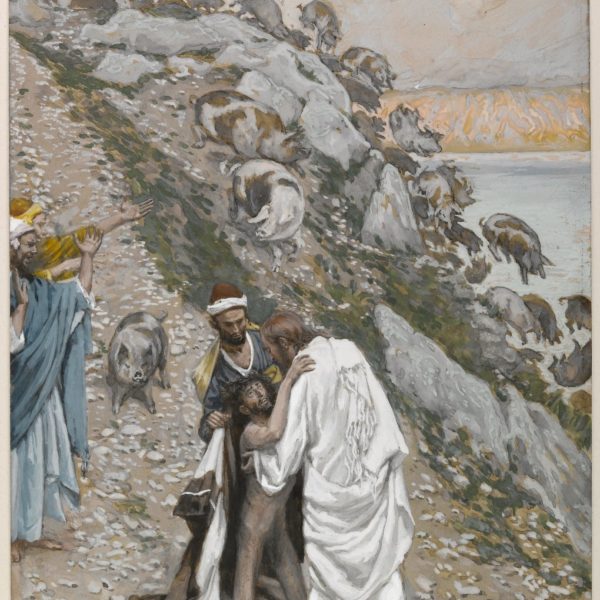

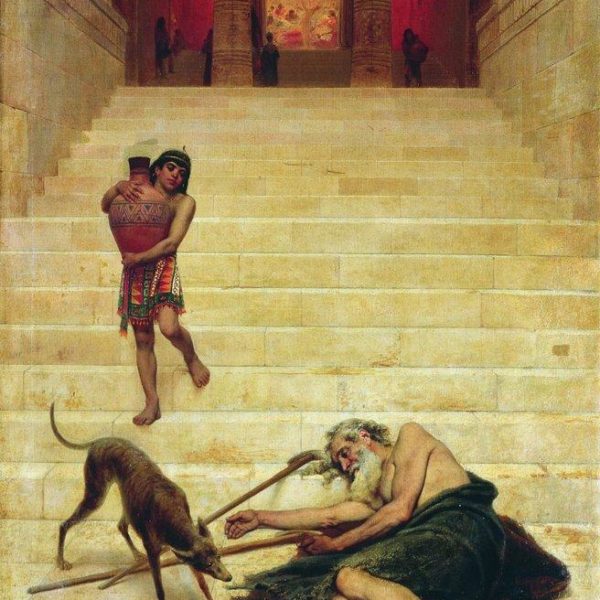

Jesus’ story of the Rich Man and Lazarus is a challenging account of the one neglected at the gate, who ends up being exalted, while the one at ease within is cast out. This story has a particular contemporary resonance in the context of the recent events surrounding the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

As in the case of the unjust steward in Luke 16, a radical change in our handling of money is required, if we are to survive the great day of accounting that is to come. We must use the limited time and opportunity remaining to us to escape the clutches of our greed and expend our dirty money to pursue true and incorruptible riches.

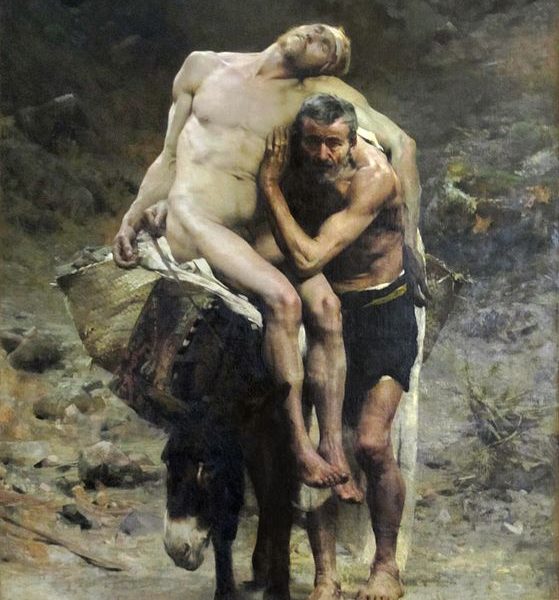

In response to a question designed to test him, Jesus presents a lawyer with a series of questions in response, which evade his trap and undermine the lawyer’s attempts at self-vindication. Through his conversation, he reveals the importance of asking the right question.