In the Passover we find a myth of the foundation of a nation that differs markedly from the contractarian myths of the Western liberal tradition. It disclosure of the sacrificial basis of the political order offers us a hermeneutical key for understanding the roots of our own nations and helps us to understand how we might be established as communities of faithful witness to them.

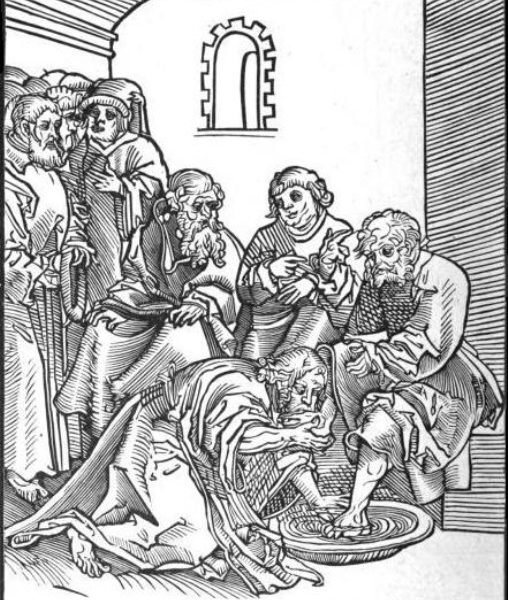

Christ’s actions on Maundy Thursday present a challenge to Enlightenment views of property. Through the Eucharistic vision of Christianity, we become more like Christ, and we do so together enveloped in an all-encompassing commandment of love: we grow together, not only in that we all simultaneously grow, but the barriers between us dissolve and our original love is mended.

. . . The concept undeniably has a certain appeal, and few slogans are better calculated to capture the imaginations of the young and disaffected than “Towards eucharistic anarchism” (Bill Cavanaugh’s phrase in Radical Orthodoxy) and other such brazen assertions of liturgical politics. But in all the talk of eucharistic politics, a surfeit of aesthetic appeal seems to have usually compensated for a shortfall of logical clarity.