Later Calvinist texts, like the famous Vindiciae, Contra Tyrannos, would go further than the Reformer and claim natural law defenses for resistance.[1] I want to contend that Calvin’s principles provided a basis for this kind of argument, even though Calvin did not take this route in his own thinking. And the place to begin this line of argument, I think, is with his comments on the sixth commandment.

…Just considering very recent history, from the Arab Spring to South Sudan to Ukraine, revolution and resistance has been a very real part of our world. The popularity of this idea in cultures spanning the planet gives the political theologian pause. Is the apparent widespread support for this kind of act an expression of common grace, a preservation of the light of practical reason in spite of the fall? Or is it simply an expression of the rebellion bound up in the heart of our fallen species?

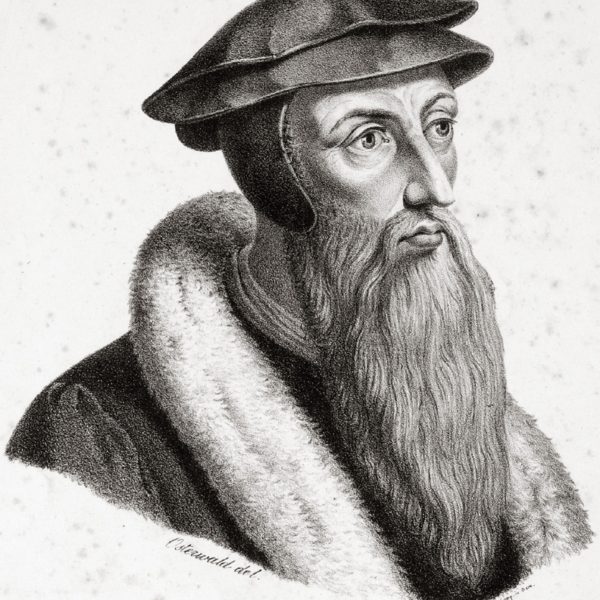

One of the great paradoxes of John Calvin’s political theology can be captured in terms of two of the phrases the reformer used over and over throughout his writings. On the one hand, he emphasized, “the kingdom of Christ is spiritual.” On the other hand, through the kingdom of Christ God is bringing about the “restoration of the world.”

In a sermon on 1 Tim 6:1-2, John Calvin commented,

“…but they were slaves, of the kind that are still used in some countries, in that after a man was bought the latter would spend his entire life in subjection, to the extent that he might be treated most roughly and harshly: something which cannot be done amidst the humanity which we keep amongst ourselves. Now it is true that we must praise God for having banished such a very cruel brand of servitude.”[1]

Viewed in the light of liberal commitments, Calvin’s chief error appears to be his presumption that the civil magistrate has not only the right, but the duty, to use his coercive office to enforce “piety.” As Calvin argues, the political ruler must recognize his duty “to cherish and protect the outward worship of God, to defend sound doctrine of piety and the position of the church” and to “form our social behavior to civil righteousness,” thus promoting social peace (Institutes 4.20.2). To liberals, of course, this appears dangerously intrusive.

In recent years, a number of theologians and legal historians have argued that the early modern Reformed tradition was a significant source for the development of various liberal doctrines. Scholars such as Nicholas Wolterstorff, David Little, and John Witte have traced modern doctrines of individual rights and the separation of church and state back to various Calvinist thinkers. Witte has been the most prolific, writing dozens of articles and several books on the topic over the past couple decades.

Unlike some other second-generation Reformers, we do not have to read between the lines to find a two-kingdoms doctrine in Calvin. On the contrary, he is far less ambiguous even than Luther in setting it out at the center of his theology, inviting the question of why Calvin studies have until recently largely ignored the theme. The doctrine appears in the all-important chapter III.19 of the Institutes, as Calvin concludes his discussion of justification and prepares to transition to his massive Bk. IV, entitled “The External Means or Aids By Which God Invites Us Into the Society of Christ and Holds Us Therein.” Inasmuch as Calvin scholarship has attended at all to his two-kingdoms idea, it has frequently assumed, as VanDrunen does, that in delineating the “two kingdoms,” Calvin intends to delineate the two distinct institutions within this sphere of external means—church and state. However, from a structural standpoint, it is more compelling to see his distinction of the two in III.19 as a center-post, with the “spiritual government” pointing back to his discussion of the inward reception of the grace of Christ in Book III, and the “temporal government” pointing forward to his discussion of the external means in Bk. IV—on this basis, both the visibly-organized church and the state would constitute external means in the temporal kingdom. Certainly Calvin’s word choice in describing the two seems to bear out such a reading…