Six months or so after Lehman Brothers disappeared, and two weeks after the Dow Jones hit a twelve-year low, the creators of South Park ran an episode called Margaritaville, the primary storyline of which recounted the failed attempt by one of the boys to return the eponymous blender that his idiot, moralizing father had bought. In a gleefully sloppy primer on the financial crisis, Stan follows the increasingly inscrutable chain of capital from the profligate consumers, to shady third-party financiers, to the securities bundlers of Wall Street, and ultimately, to the public sector ex post facto debt assumers. At the heart of financial darkness, Stan’s odyssey takes him to the Treasury Department where a tribunal of economists determines the value of his margarita maker to be ninety trillion dollars, a calculation determined, it is subsequently revealed, through a divining process involving men in powdered wigs, a kazoo, and a decapitated yet still ambulatory chicken tossed onto a wheel-of-fortune style game board labeled with a range of monetary, fiscal, political maneuvers: Socialize/ Let Fail/ Coup d’etat/ Bailout!

The pursuit of truth and justice is often onerous and taxing. The incremental gains accomplished by strikes and protests, grassroots organizing, and community coalitions pale in comparison to the large-scale success achieved by corporations and the governmental institutions who collude with each other. The quest to halt imperialistic conquests by the American war machine, ameliorate poverty, reform a racist and unjust judicial system, and empower communities can often seem like a dead end street, but the light of hope still shines through the darkness […..]

As the humanities have rediscovered religion, new sorts of questions are being asked about religion and politics. Religion is no longer imagined as a check box, as the social sciences would like to see it: something you have or don’t, something that comes in one of several flavors of belief. Now that religion is not only about belief but about practices and ideas, with histories, intertwined with other practices and ideas, the intersection of religion and politics is no longer a point, but a varied terrain with multiple dimensions. […]

Although often lost in a generic celebration of the giving of the Spirit, this text is one that is filled with questions of ethnicity, language, and diversity. It speaks to the American debate of whether this nation can or should be a melting pot that blends and ignores culture and ethnicity or a mosaic and celebration of the diversity that exists in our midst. But first, some background:

In our text today Peter embraces the Gentiles as fellow Christians after he observes them being filled with the Holy Spirit. Earlier Peter had received a vision in which he was commanded to eat things that he considered unclean. Perplexed by the vision, Peter realized its meaning after he was led by the Lord to the house of Cornelius, a Gentile who believed in God. Peter never would have gone inside Cornelius’ home since Jews did not visit with Gentiles, nor enter into their homes. Because of his vision, however, he realized that God was doing a new thing, and he received the Gentiles into the household of faith as brethren….

The word ‘blurred’ perfectly captures the context within which urban political theologies in the twenty-first century are forged. The ‘blurring’ of previously ‘solid’ cultural demarcations, ethnic identities, class divisions, political ideologies, religious boundaries and urban geographies is not new as Manuel Castells and Edward Soja noted over a decade ago. In a globalised century however this ‘blurred’ world has become the norm and not the exception. Unless contemporary theologies grapple in depth with this ‘blurred’ context they will become increasingly irrelevant to all but a declining religious minority. The step into this fluid city challenges what might be called ‘solid’ theological and ecclesiological models. Such stepping out also raises key questions about the extent to which so-called ‘fresh’ expressions of church and what Pete Ward has called ‘liquid church’ are ‘fresh’ enough or ‘liquid’ enough to engage credibly with the ‘blurred’ ‘post-religious’ twenty-first century world…

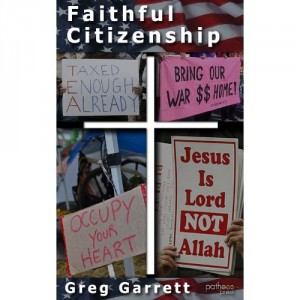

The media has been flush with stories and commentary on religion in the public square. When a panel of religious leaders is called to testify before a congressional oversight hearing, how could it be otherwise? For a country which has canonized a separation between religion and governance these spectacles of power and politicking quickly call into question the Post-Christendom thesis….

This procession down to Jerusalem is one of those very public moments in Jesus’ ministry. It could be called his most brilliant act of political theatre. Jesus proceeds toward Jerusalem, with a crowd that undoubtedly boasts some of the same sorts of outsiders Jesus has been connecting with all along: sinners, the possessed, the sick and blind, women, and foreigners. The crowd that shouts Hosanna would have been laughed at by any sensible members of society who happened upon this odd ritual. Much like I imagine today those with a high sense of their own political value would little understand what compelled these odd folk to gather as they had, creating trouble when they had little to gain but jail cells and crosses…