Uprooting a fear without replacing it with helpful information is redundant. Therefore, it is time to shift focus from merely quashing anti-vaccine sentiment to intentionally building vaccine confidence. Nigeria provides a heartening case study on how this can be achieved.

Justice fails where civil law and order are privileged over peoples’ ability to determine their destiny by confronting affronts to their dignity by legitimate powers. Let me offer two examples. I confess I am still in love with the Occupy Movement (OWS).

Within Christian traditions, one may be met with this provocative question: does “political theology” or “social ethics” sponsor liberative practices oriented towards human flourishing? Interestingly, the framing of this question requires one to choose a side. One must argue that either political theology or social ethics is poised to address the myriad theo-ethical issues we face, particularly issues of difference, pluralism, and alterity. I believe that this is a false framing of the question.

The Ethics section of the American Academy of Religion has organized an important panel investigating the question “Which is it – Political Theology or Social Ethics? And Does It Matter?” at next week’s Annual Meeting in San Diego. We invited the four panelists to contribute preliminary essays on this theme for discussion here, and three have been able to contribute: Ted Smith of Emory University, Keri Day of Brite Divinity School, and M.T. Davila of Andover Newton Theological School. We will be posting these over the next several days, beginning with Ted Smith’s.

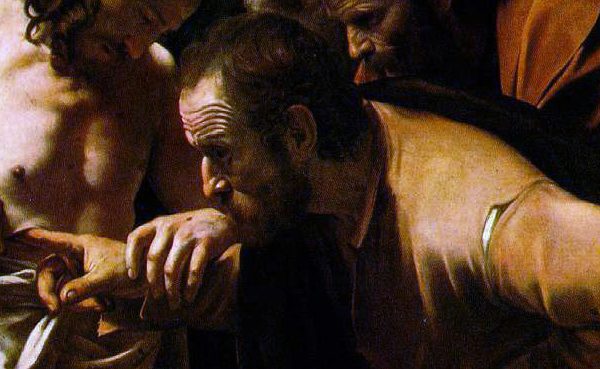

The encounter of Mary Magdalene with the risen Christ provides us with a model for understanding political theology. The elusive presence of the resurrected one and the emptiness of his tomb forbid all our attempts to secure his presence in our praxis and open up new ways of perceiving our social task.

Some challenges and opportunities are the same on either side of the pond for those of us teaching political theology. Those teaching in seminaries and other ‘confessional’ contexts will find the same resistance to ‘politicizing’ faith from conservative students and the same blasé assumptions from liberal students who obviously already have this all sorted because they are good liberals, both theologically and politically (more on these challenges in Part 3, next month). Those teaching in liberal arts universities will share similar struggles with how (or if) the discipline can be normative or formative in these contexts. And we will all share the wonderful opportunities involved in drawing students beyond their inherited binary views of the theological and the political. In other ways, the challenges and opportunities differ considerably on either side of the pond….