The United States is comprised of a religiously diverse citizenry, which leaves officials to balance the tension upheld by a constitution that simultaneously prevents the establishment of a national creed and yet preserves one’s right to freedom of religion. In practice, officials in the United States cannot legislate theology, but they can, and do, use theology to legislate.

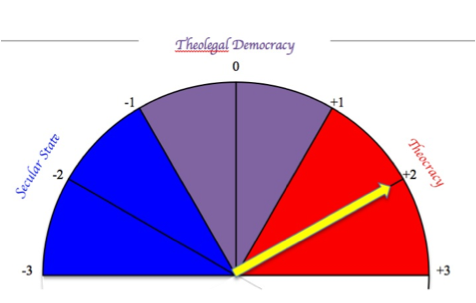

As a result, the United States is not a secular democracy where laws guarantee freedom from religion and dismiss theological rhetoric in the political process; neither is it a theocracy, where a single religion prescribes all laws. Whether we like it or not the United States is a theolegal democracy.

I want to argue here that the term “political Islam” is in many ways a misnomer, because the Islamism that is meant to instantiate it has been unable to appropriate politics as a way of dealing with antagonism either institutionally or even in the realm of thought. Looking in particular at the form Islamism took with one of its founding figures, the twentieth century writer, and founder of the Jamaat-e Islami in both India and Pakistan, Sayyid Abul a’la Maududi.

The revival of interest in political theology at the turn of the millennium began with Islam, then moved to Christianity. In the wake of September 11, 2001, it became clear that not all religion was fading away, nor was all religion confined to the private sphere. The evidence: radical Islam. But the obvious risk of Islamophobia that accompanied a focus on Islam as anomalously growing and anomalously public prompted some scholars to explore how Christianity itself was neither fading away nor thoroughly privatized. Instead of focusing on Islam as anomaly, political theology provided a framework for complicating the West’s story of itself, for probing the complex and continuing relations between religious and political ideas.