The discourse of terrorism is itself an ideology linked to conceptions of truth and identity, life and death, law and justice. But there is also a terror that exists in silence, a terror that bears no name because the life it destroys is not even recognized as having lived.

When the Senate issued its report on CIA torture in December of 2014, the House Intelligence Committee chairman—Mike Rogers, a Republican from Michigan—questioned the wisdom of releasing the report, warning that the report’s release would have dire consequences for the United States. Moving forward, he suggested that politicians needed to help the CIA talk differently about its activities.

. . . We live in an age of terror, but not because we have been terrorized by the Other. Rather, the terrorism we recognize is the consequence of an a priori distinction between lives that matter and lives that don’t. Slahi, confined at Guantanamo since January 2000 without charge, represents the figure of terror.

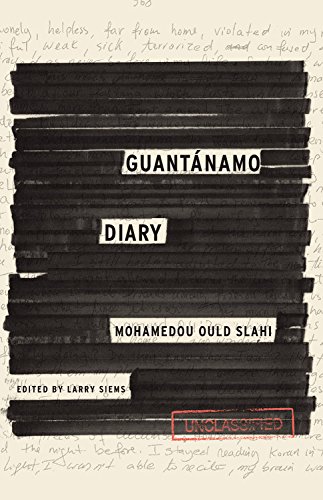

He faces no criminal charges. Indeed, a U.S. judge ordered him released five years ago. Nevertheless, Mohamedou Ould Slahi remains in Guantánamo Bay, after more than thirteen years in captivity. He was snatched out of his home country of Mauritania shortly after 9/11/2001, and then renditioned to Jordan, Afghanistan, and finally Cuba. In U.S. custody he has endured beatings, threats, sexual assaults, sensory deprivation, lengthy exposure to cold temperatures, food deprivation, deprivation of medical care, stress positions, and forced nudity.

Too often, scholars enamored with Foucault’s work assert that physical torture waned with modernity. However, this is an uninformed understanding of penal history. From their inception, U.S. jails and prisons frequently tortured inmates.

I have been writing about torture for the last decade. Does the recently released summary of the Senate report reveal anything that requires reconsideration of my earlier work? Surely, it is not news that the Bush administration, particularly in the first term, pursued a practice of torture. Nor is it news that the practice was not successful. After all, the turn to torture was puzzling partly because we have long known that it is not an effective means of obtaining information. In fact, torture is best understood as a practice not of inquiry but of communication.

Last month, speaking to a crowd in St. Peter’s Square, Pope Francis declared that “to torture persons is a mortal sin. A very grave sin.” Relating his comments to the United Nations’ International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, the pope condemned “every form of torture and invite[d] Christians to commit themselves to work together for its abolition and to support victims and their families.” These exhortations paint a very different picture than UN Committee Against Torture findings on the Vatican’s handling of sexual abuse within the church.