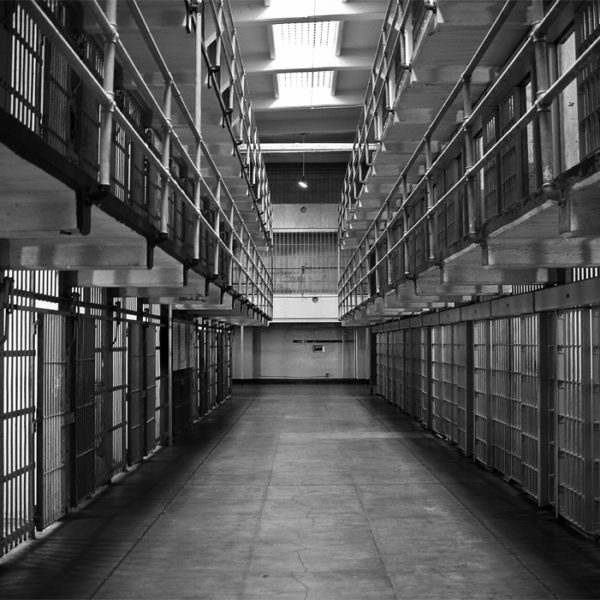

There is a good case to be made that the American criminal justice system is itself criminal. Up until around 1980, all statistics we have suggest that the incarceration rate varied at around 100 inmates per 100,000 people. After about 1977, and especially after about 1982, the rate began to rise; in 2008 it was over 700 prisoners per 100,000, and while it seems to have begun a modest decline in the past few years, it remains over 700. In this context, “American exceptionalism” is not an overstatement; the United States is effectively the largest incarcerator in the world; the only states near us are Cuba and North Korea.

We are happy to announce the publication of Vol. 16, Issue 3 of our journal, Political Theology. Unlike several recent issues, this issue is not organized around a single theme, but brings together a range of high-quality contributions on diverse topics in contemporary political theology.

When the Senate issued its report on CIA torture in December of 2014, the House Intelligence Committee chairman—Mike Rogers, a Republican from Michigan—questioned the wisdom of releasing the report, warning that the report’s release would have dire consequences for the United States. Moving forward, he suggested that politicians needed to help the CIA talk differently about its activities.

He faces no criminal charges. Indeed, a U.S. judge ordered him released five years ago. Nevertheless, Mohamedou Ould Slahi remains in Guantánamo Bay, after more than thirteen years in captivity. He was snatched out of his home country of Mauritania shortly after 9/11/2001, and then renditioned to Jordan, Afghanistan, and finally Cuba. In U.S. custody he has endured beatings, threats, sexual assaults, sensory deprivation, lengthy exposure to cold temperatures, food deprivation, deprivation of medical care, stress positions, and forced nudity.

. . . In the book I think about what it would mean to see Brown as a “Great Criminal” who did wrong but can still be read as a sign of a divine violence that breaks the hold of the slave system on social imaginations and so makes possible not just new ways of seeing the world, but new ways of acting, new ways of connecting with others, and new ways of deliberating together.

Johannes de Silentio admits that “Abraham I cannot understand, in a certain sense there is nothing I can learn from him but astonishment.” Can we say the same about John Brown? Smith clearly wants us to learn from him and from what happened at Harpers Ferry, not to mention what happened six weeks later. But it is a curious sort of learning, since Brown’s exceptional status — like Smith’s subtitle — acknowledges the limits of ethics in making sense of the violence enacted by, and on, such a singular figure.

I think that a politics of penitence and repair can disrupt old divisive racial patterns, potentially enabling the emergence of new racial communities not marked by old forms of racial hatred and violence. Smith’s argument for penitence and repair is compelling and I do think that a Christian political theology calls upon us to consider these two important practices. Smith presents a theological discussion of pardon that eventually takes us to repentance and repair when addressing racial wounds.

Ted Smith delivers an unprecedented thesis about Brown’s violent assault on slaveholders as the human side of a “divine violence.” From beyond the limits of any earthly system of political justice and social ethics, this is a divine judgment against the validity of an entire system of political ethics. Addressed, for one, to American ethicists today — both those who teach and study in the university and those who voice their ethical judgments on street corners, in churches, and across the Sunday dinner table — Smith’s words, while gently spoken, deliver their own report of divine judgment.

A bishop recently said that 90% of the homilies he has ever heard can be boiled down to two words: “Try harder.” Of all the things that Ted Smith’s book does well, the most compelling for me is his attempt to critique the ethical confines to which reflection on politics and violence — along with so much else — is often limited.

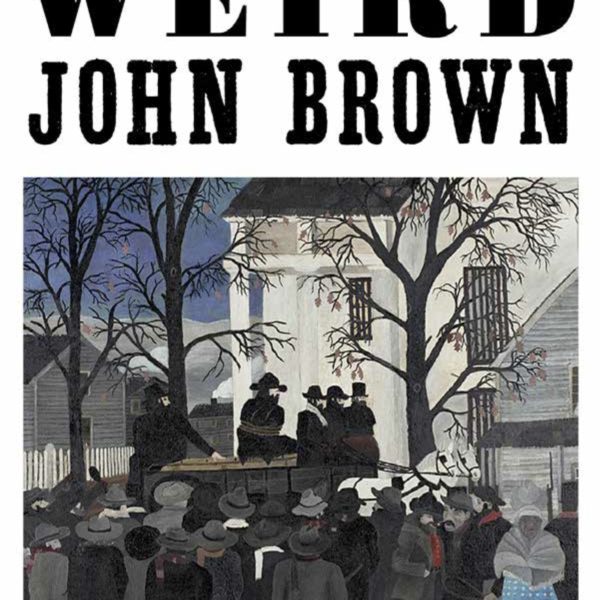

In conjunction with the Marginalia (part of the LA Review of Books), Political Theology Today has organized a symposium on Ted Smith’s extraordinary new book Weird John Brown: Divine Violence and the Limits of Ethics. Over the coming two and a half weeks, we will host responses to the book from E. Brooks Holifield, William Cavanaugh, Peter Ochs, Keri Day, and Andrew Murphy, concluding with a response to the responses by author Ted Smith. Here is the first response, from E. Brooks Holifield of Emory University.