Romans 13:1-7 has stood as one of the most important texts throughout the history of Christian political thought, but like so many biblical texts, has proven capable of being put to the service of several different—even contradictory—ends. The 16th century in particular stimulated several different readings of the passage, readings which have continued to remain popular down to the present day.

The original sin of man is the torpor and corruption of the chaotic matter in which he may be said to be born.

The Reverend Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) is best known for An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798). Here this classical economist argues that human beings are caught between two drives, lust and hunger – or, being the polite reverend that he was, population and subsistence.

Back in September, I suggested that the current literature on just intelligence theory may be unduly influenced by jus contra bellum thinking; that is, a strain popular among the more pacifistic elements of just war thinkers which tends to elevate either the jus in bello principles (i.e. immunity of noncombatants from direct attack and micro-proportionality) or the prudential ad bellum criteria (i.e. last resort, macro-proportionality, probability of success) over the traditionally-prior, deontological categories of sovereign authority, just cause and right intention.

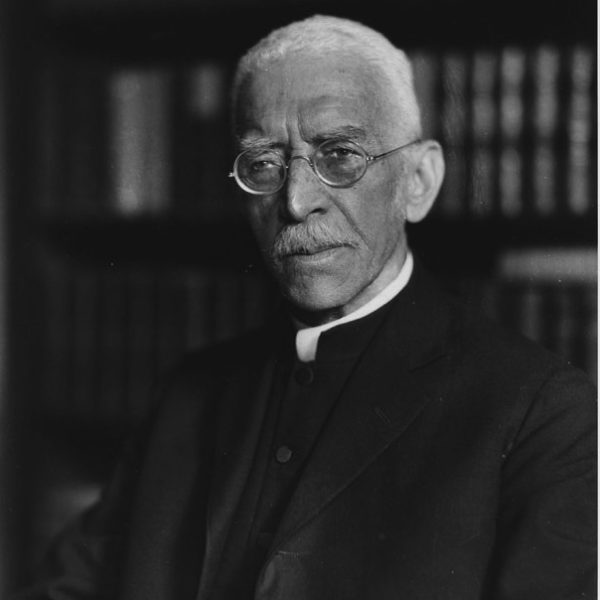

““I cannot believe that the men who occupy the pulpits of this land, assuming that they are men of ordinary intelligence and common sense and that they have, as they ought to have as leaders, some little knowledge, at least, of the Word of God, are without some convictions on the subject (of race prejudice), that they do not know that it is wrong, contrary to every principle of Christianity.”

. . . Often much more important than what people argue is how people argue. . . . Many whom we may have hastily taken as kindred spirits, because they happen to have reached some conclusion we moderns take for granted, turn out on closer inspection to have been motivated by wholly different concerns, so that the convergence is largely illusory. Others, however, whom we might be apt to dismiss as barbaric for their unenlightened ideas, turn out to have been strikingly liberal-minded.

For the sake of the following argument, I would like to grant the premises of Max Weber’s idealist argument: religion and culture (superstructure) are causative agents in socio-economic change. As is well known, Weber argued that Calvinism acted as a crucial vanishing mediator for capitalism. It provided the cultural, behavioural and religious framework that enabled capitalism to establish itself and gain ground.

2013 marks the 50th anniversary of the climax of the modern civil rights movement in the United States. Amidst the national reflection, some Protestants have been led to critically reexamine the doctrine of the “spirituality of the church” which has had a foothold within segments the Presbyterian Church for nearly two centuries.

I am grateful to Bill Cavanaugh for taking the time to respond to my blog post of two weeks ago, “Modernity Criticism and the Question of Violence,” and giving me the opportunity to clarify better the nature of my criticisms. Clearly such clarification is in order, as Cavanaugh’s response seems to have struck off in something of the wrong direction, defending theses that were not really under challenge. If I may adapt the opening from his post, Cavanaugh’s response would raise significant difficulties for the thesis of my critique if (1) the argument of that critique were directed against The Myth of Religious Violence and (2) my purpose was to endorse Steven Pinker’s triumphalist progressivism. The first of these premises is false, and the second is highly questionable.

Brad Littlejohn’s blog entry here last week would raise significant difficulties for the thesis of my book The Myth of Religious Violence if 1) the argument of that book is that modernity is more violent than previous epochs and 2) Steven Pinker has proven that modernity is in fact less violent than previous epochs. However, the first of these premises is false, and the second is highly questionable.