Parts of the world tremble again at religiously inspired revolutionary activity. Too easily do we forget that very similar forms of such activity have appeared in earlier periods of time, even if the content was somewhat different. Thus, in the nineteenth century, the socialists organised, while the anarchists threw bombs and carried out assassinations. And in the sixteenth century, Thomas Müntzer and the Peasants organised and theologised for the revolution, while the Anabaptists were seen as the extremists, the terrorists who had to be eliminated.

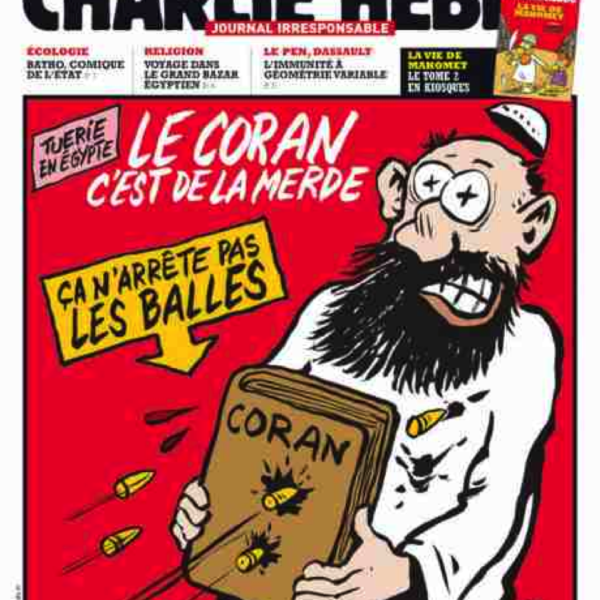

In the midst of the Arab uprisings, the now famous magazine Charlie Hebdo published one of their traditional satirical covers. They titled the issue “Killings in Egypt” and drew the figure of a Muslim religious activist who was riddled with bullets. The subtitle was more than eloquent: “The Koran is a piece of shit,” the agonizing Muslim was made to say, because “it does not stop bullets.”

This is the first of a series of five articles on understanding China today. The articles cover politics, economics, culture and religion, since all of these are important for making some sense of what is happening. Each topic is approached from the Marxist tradition, for this is a key that is too often ignored. The

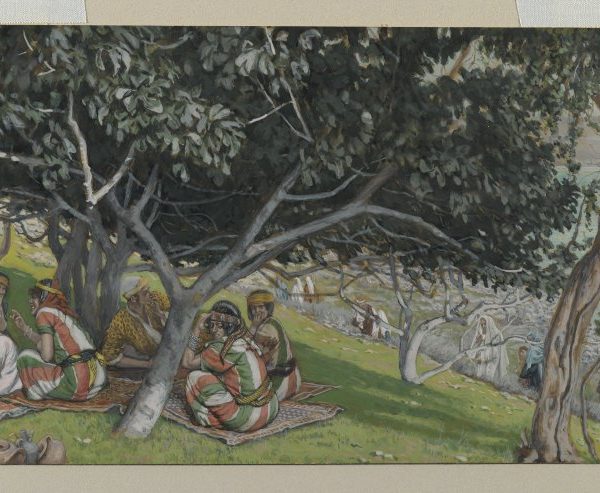

Jesus’ calling of Nathanael in John 1 illustrates the way in which God’s vision of us precedes our own. The primacy of God’s vision has implications for our politics and economics, unsettling our assumption that the world is measured and determined by our sight and valuation.

In the public imagination, dualism rules the day. The dualistic mindset sees things in pairs, and tends to perceive only absolutes. Evil must be balanced by good. The ways of righteousness have nothing to do with the ways of wickedness. Such dualism has characterized the fevered public discussion following the incidents involving Michael Brown and Eric Garner.

Call for Papers: Political Theology has expressed interest in publishing a special issue on the theme of intellectual virtue and civil discourse (subject to editors’ and referees’ approval). Due date: June 15, 2015.

Intellectual virtues are commendable traits of thought that facilitate the acquisition of knowledge and understanding. Public discourse would be much better off when citizens exercise such virtues, it seems.

“When all the women were dead, the jihadists burned their bodies inside the houses. After they had finished with the women, the jihadists went back to …where they had locked the children. ‘They brought out the little kids – two, one and a half, three years old – they took them out holding on to each other. They took the groups and killed them with knife stabs’.

Issue 16.1 of the journal Political Theology is devoted to theology, plurality and society. Below guest editor, Dr. Peter Scott, introduces the issue.

Must a religiously plural society fall apart? How does theology process plurality? This special issue of Political Theology addresses the issue of plurality from a variety of theological perspectives. It began life as an attempt to respond to an earlier special issue of the journal, which assessed critically the political and theological phenomenon of Red Toryism. In the earlier volume, there was persistent criticism of an appeal to a common tradition in the context of a religiously plural society.

At moments of crisis, it can be the responsibility of committed individuals to secure and represent the self-understanding of the community or nation to which they belong, to provide the seed from which the entire social body can be renewed. Within easily neglected political dimensions of the baptism of John we may be recalled to our potential and vocation as political individuals in this regard.