For the past two weeks I have made my annual pilgrimage with university students to Vienna, which because of the strong United Nations presence and the hundreds of NGOs specializing in international humanitarian services and outreach is often known as the “gateway city” for globalization.

We always end the course with a two-hour train ride west of the city along the Danube to the Denkstätte (“memorial”) that is the Mauthausen Concentration Camp, an originally preserved site of the monstrous brutality and anti-human obscenities inflicted on a vast diversity of different peoples now at least 70 years ago by the Third Reich.

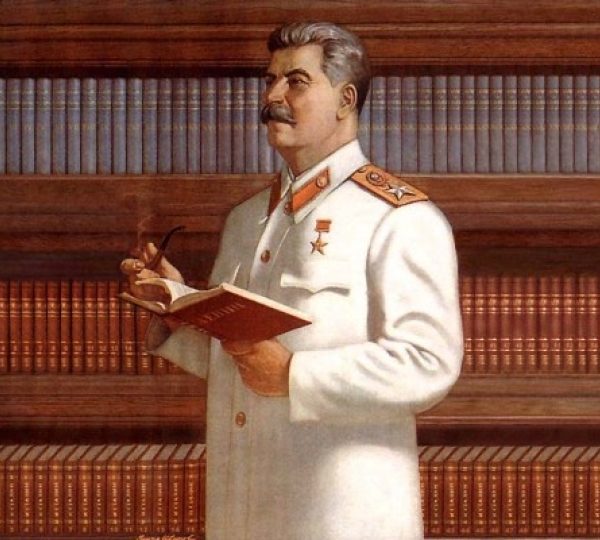

Political Theology Today is proud to announce that one of our Contributing Editors, Roland Boer, is the winner of the Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Memorial Prize for 2014. The prize is “awarded for a book which exemplifies the best and most innovative new writing in or about the Marxist tradition.” In this case, it was awarded for In the Vale of Tears (2014), but also in recognition of the whole Criticism of Heaven and Earth series. We have invited him to summarize his extraordinary work in this area for our readers.

…Instead of treating contemporary consumerism as a wholly negative phenomenon, Augustine suggests we look at the issue differently. The behaviour of the shopper or spiritual tourist is the way it is because of the deep structure of the human condition. The longing for fulfilment is at root an existential need: a secularized version of the call at the heart of Augustine’s Confessions: ‘You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you.’

The language of recognition is of such frequent use that its presence in everyday and academic discourse is striking, and yet critical examination of its meaning remains largely absent. Its frequent use is evident in the legislative acts promulgated, the public policies written, and the social struggles waged in the name of it. Its application touches upon a broad spectrum of issues ranging from multiculturalism to national sovereignty, from matters of international human rights to social movements within feminism and civil rights.

Righteous Joseph does not publicly shame his fiancée Mary, breaking with common practice in an honor and shame culture. The angel that appears to him calls him to take a further step, to assume the role of father to Mary’s curious child.

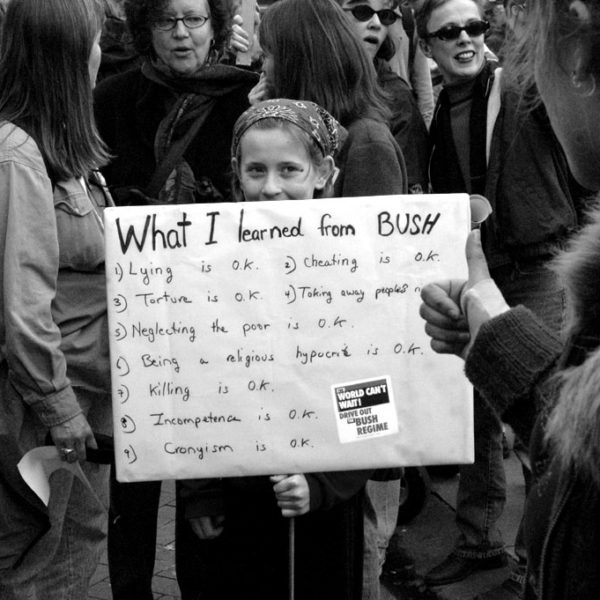

So what do the findings I have shared indicate for the future of the Christian right? They demonstrate despite the Republicans recent 2014-midterm results, that millennial Christians are more ambivalent about politics than their parents. According to Pew Research, millennial turnout in 2014 was down 6 points on the 2012 Presidential election, whilst there was 6 point increase amongst baby boomers aged 50-68. Older white Christian males swung the election in the GOP’s favour. Though this temporarily bodes well for GOP-Christian right relations, it is clear that there will be a significant age-gap problem very soon, for partisan ties are very much weaker amongst millennials.

Following Bush’s consecutive victories in 2000 and 2004 the Christian right have been labeled the ‘backbone’ and ‘base’ behind the Republican Party’s electoral successes.[1] Evangelical born-again Christians constitute around 26% of the US electorate according the latest Pew Research poll, of whom three-quarters consistently vote Republican.[2] For forty years the considerable convening power of these faithful conservatives have made them an attractive constituency for Republicans to court. Aligning with their social and cultural concerns, this relationship has generated a distinguishing feature amongst Western politics, the American ‘values voter’.