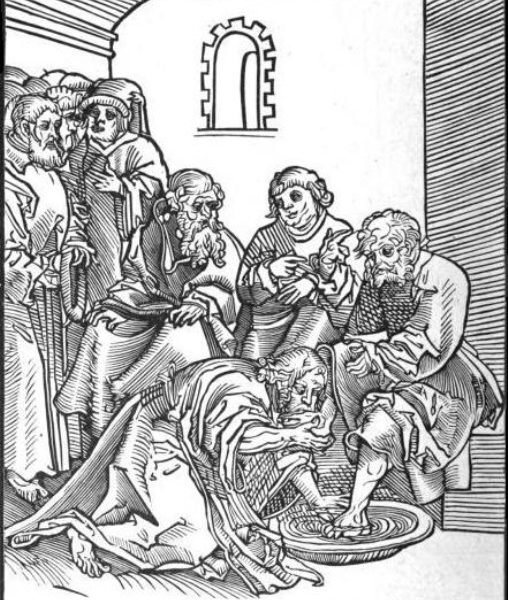

Christ’s actions on Maundy Thursday present a challenge to Enlightenment views of property. Through the Eucharistic vision of Christianity, we become more like Christ, and we do so together enveloped in an all-encompassing commandment of love: we grow together, not only in that we all simultaneously grow, but the barriers between us dissolve and our original love is mended.

The encounter of Mary Magdalene with the risen Christ provides us with a model for understanding political theology. The elusive presence of the resurrected one and the emptiness of his tomb forbid all our attempts to secure his presence in our praxis and open up new ways of perceiving our social task.

This is the fourth, and final, post in a series that was kick-started last September with a short discussion of how the growing field of just intelligence theory might be overly influenced by jus contra bellum thinking, or what Tobias Winright has coined “the presumption against harm version of just war theory.” This particular variant of just war theory is defined at its core by a presumption against war or a presumption against the use of force.

“That which does not kill us makes us stronger,” Nietzsche wrote.

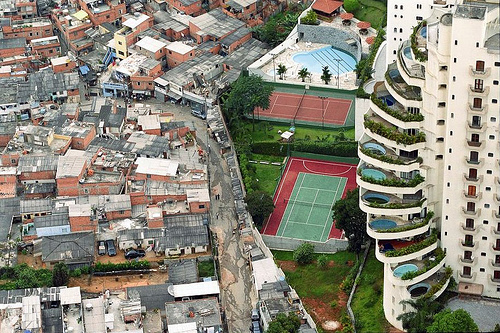

As the global neo-liberal order slowly unravels before our eyes, that recognition holds more true today than ever.

In our social imaginary, love has become the major existential goal of our times, which is capable of providing all of us with a sense of worth and a way of being in the world. . . . In our political imaginary, law has become our highest political ideal. Life with the rule of law marks us out as a civilized nation and people.

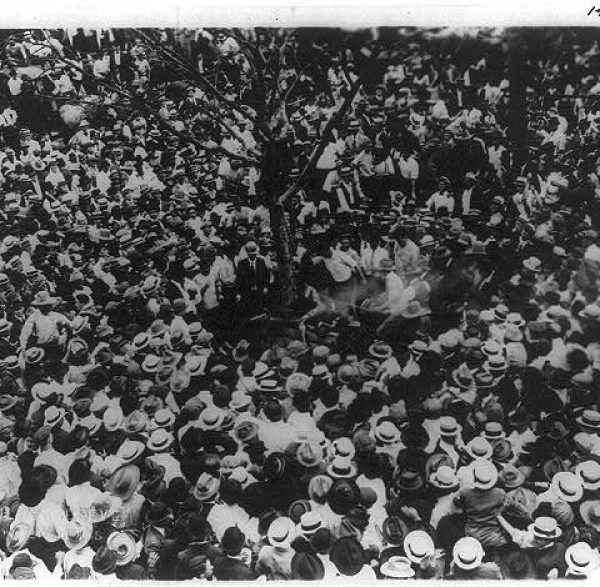

The contagious violence of a frenzied mob brings about the sentencing of Jesus to crucifixion by Pilate. The operations of the scapegoat mechanism are revealed in the record of these events and, as we reflect upon them, we will learn to identify its operations within our political life. In Christ we find an alternative model for desire, which can enable us to resist the seduction of unity through violence.

Several of my friends joined a Facebook meme soliciting a list of the ten books that most influenced you. I thought myself too cool to participate, but if I had, Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble would have been on my list. I devoured it one winter break when I was home from college. At the time, I was fascinated by the world of feminist theory to which Butler introduced me.

While many analysts contend that a carbon tax is the most effective and efficient climate change mitigation policy available to the U.S., one of the most significant obstacles to the legislation of a national carbon tax in the U.S. is American’s basic aversion to taxation. In view of Americans’ antipathy towards taxation, the Thomistic virtue jurisprudence proposed by Cathleen Kaveny in her book Law’s Virtues can dispose Americans to support a national carbon tax.