In 2008, I worked in Ramallah as a journalist and interim editor for the Palestine Monitor, a web-based news source committed to “exposing life under occupation.” I traveled throughout the West Bank, writing several articles about the village of Ni’lin, whose olive groves and roads are fractured due to the construction of the separation wall.

Apparently, nonviolence and democracy are strongly connected. Recent research suggests that nonviolent resistance campaigns are much more likely than violent ones to pave the way for “democratic regimes.” . . . But what, in the world, is democracy? The term resides in a restless spectrum, so perhaps the adjective democratic should be employed more than the noun.

Over the last 6-7 years, a growing body of literature has coalesced around the idea of just intelligence theory. The burgeoning interest has resulted in the establishment of the International Intelligence Ethics Association, as well as the attendant International Journal of Intelligence Ethics. As a sub-specialty of intelligence ethics, its aim has been to integrate just war theory with intelligence collection, national security policing and domestic counterterrorism – subjects that fall in a murky “middle ground” between external and internal opponents.

NATO’s humanitarian war in Kosovo in 1999 provides the context for the central idea of this book. In that conflict, the puzzling linkage between the desire to advance human rights and military means raises far-reaching questions about the role of rights in shaping international wars. Is it possible to understand or explain wars as an outcome of perceptions of rights? How did rights, be they divine rights in the Middle Ages, territorial rights in the eighteenth century, or human rights today, become something that people are willing to fight and die for?

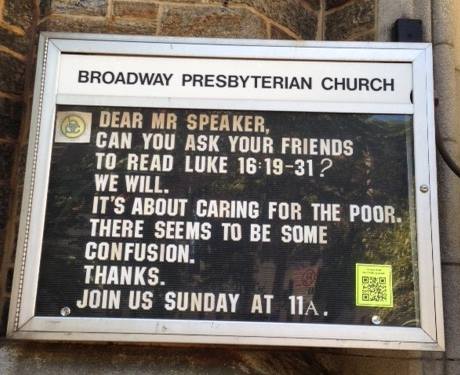

A week ago Monday, in the United States and Canada, we celebrated Labor Day, a holiday established to remind us of “the strength and esprit de corps of the trade and labor organizations.” Before we are too far past the holiday, I wanted to respond to a post by the blogger Morning’s Minion at the Vox Nova blog on the living wage, or just wage, and its role in Catholic social teaching. My point is not so much to dispute his conclusions but to complement them with some further reflections on the just wage.

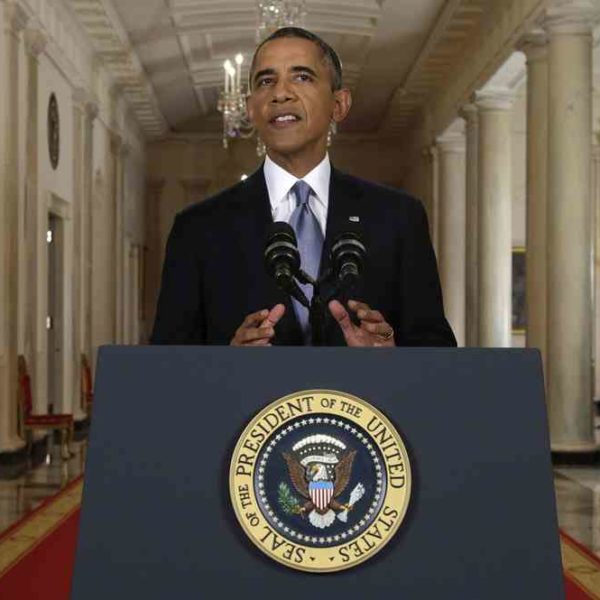

Last night in his second national address on the global response to the use of chemical weapons in Syria, President Obama asserted: “If we fail to act, the Assad regime will see no reason to stop using chemical weapons. . . . As the ban against these weapons erodes, other tyrants will have no reason to think twice about acquiring poison gas and using them.”

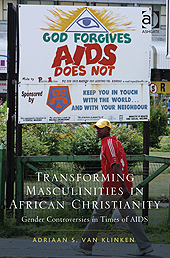

In its report Men and AIDS: A Gendered Approach (2000), the United Nations programme on HIV and AIDS, UNAIDS, has highlighted the critical role of men and prevalent concepts of masculinity in the spread of HIV and the impact of AIDS globally. Where earlier work on gender and the HIV epidemic tended to focus on women and their specific vulnerabilities vis-à-vis the HIV virus and the stigma surrounding AIDS, this UNAIDS report illustrates the shift towards men and masculinities.