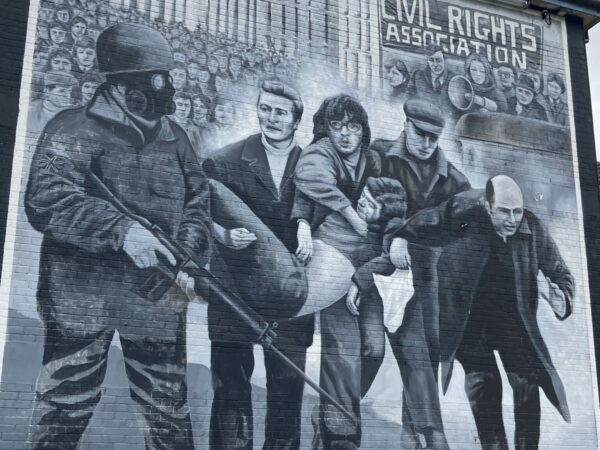

Refusal is a strong current resisting the structure of settler colonialism. It crashes, churns, and erodes the death-dealing dams of settler knowing. Its path turns away from the settler’s gaze.

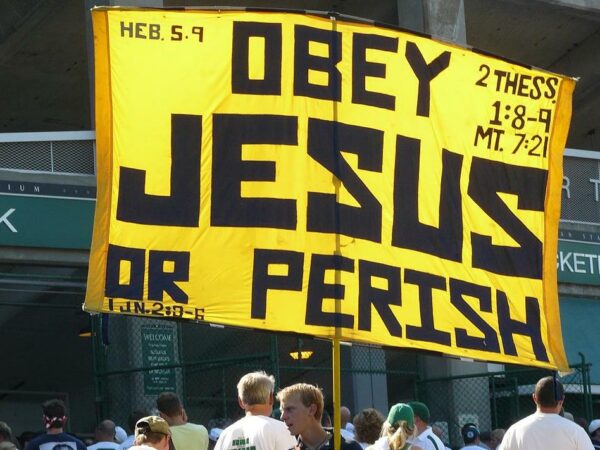

“Christ the King” on the cross offers a way of exposing systemic injustice by hanging in solidarity with victims of a violent system, but refusing to buy into the same violence that sustains it.

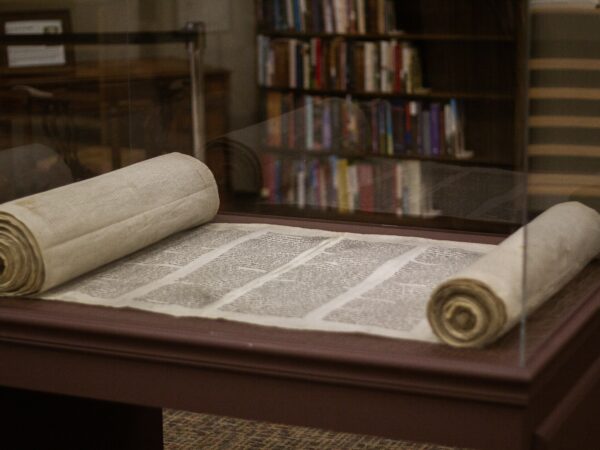

Because of its deployments within white supremacist and heteronormative projects, the natural law has not been seen as a partner in liberative ethical projects. Considerations with respect to José Muñoz’s concepts of disidentification and brownness, however, allow for a rapprochement between queer-of-color epistemologies and a Thomistic epistemology of the natural law.

To understand what’s going on today, we need to understand the 400 year story of Christian privilege in America.

The triangulation of money, sovereignty, and divinity is a good point of entry to study the mutual constitution of theological and political concepts and the questions about ultimate value and social form that they raise.

The promise of a new world, all memories of suffering erased, seems like a gift. But for

whom?