For those of us who have experienced marginalization, are we confident that God is actively seeking the lost and rejected souls in our communities? And for those of us with social privilege, do we embody this confidence by extending love to those on the margins—the outcast, the silenced, those with no voice or vote?

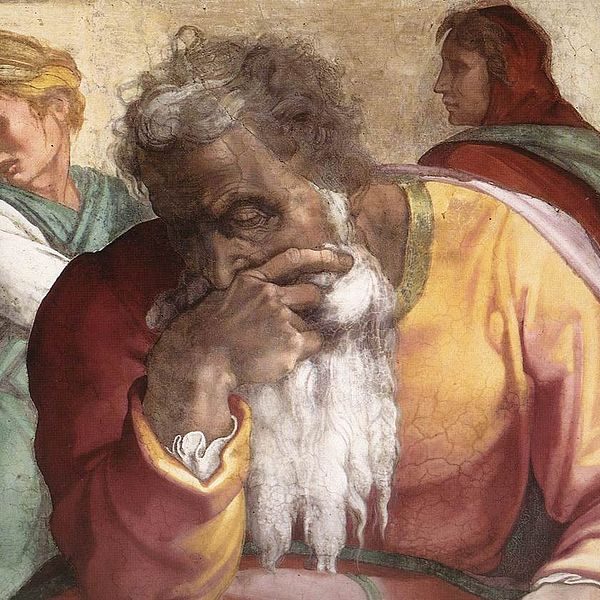

Kings and rulers often justify themselves through their pedigrees. Jeremiah’s political hope, however, does not rest on elite politics. It rests on a policy of righteousness for all.

Unlike the other covenants of the Hebrew Bible, Jeremiah’s new covenant does not focus on intermediaries, or written tablets, or monarchy, or temple, but on the divine self.

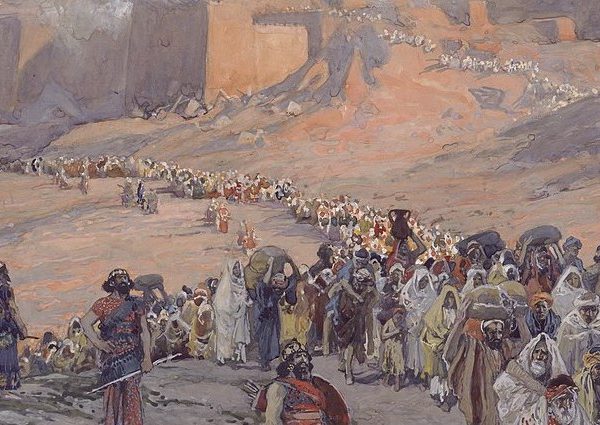

This Christmas season, what might it mean to live into the promise of hope fulfilled, when our pandemic experience means that hope strains against lost lives and lost livelihoods? Perhaps it involves visioning a redemption—one built on the social and economic implications of Jeremiah’s vision of those redeemed.

How does one turn away from a Lenten desert, so profoundly illustrated in the wastelands of plastic filled beaches, and walk towards the resurrection hope of Easter? Perhaps by remembering that Easter is coming, but its only the middle of the story.

Jeremiah’s letter is a bold admonishment to remember that we are all, together, members of the political community. Wherever we find ourselves, we must not forget that there is such a thing as the common good.

Our societies are built upon the oppression of the poor and marginalised and yet, unless we remove ourselves entirely from the web of cords, laws, taxes, products, and biological needs inherent in twenty-first century life, we are forced to participate in the oppression of others, and the destruction of our habitats. We see, we know that the world is on the brink, yet we cannot escape. Facing such a reality, Jeremiah offers us a way forward: we lament, we express our rage, we retain hope by continuing to call for change, and through it all we never allow ourselves to be numbed or silenced by the enormity of it all.