My interest in teaching a course on Political Theology came from my research on Simone Weil. I wanted to understand how the area of political theology could help me interpret Weil’s oeuvre, which often focuses on the intersection of politics and religion. To that end I decided to teach a course in the Fall of 2011 that would explore the historic development of the concept “political theology.” The course would consider how the western tradition has “thought” the intersection of politics/theology.

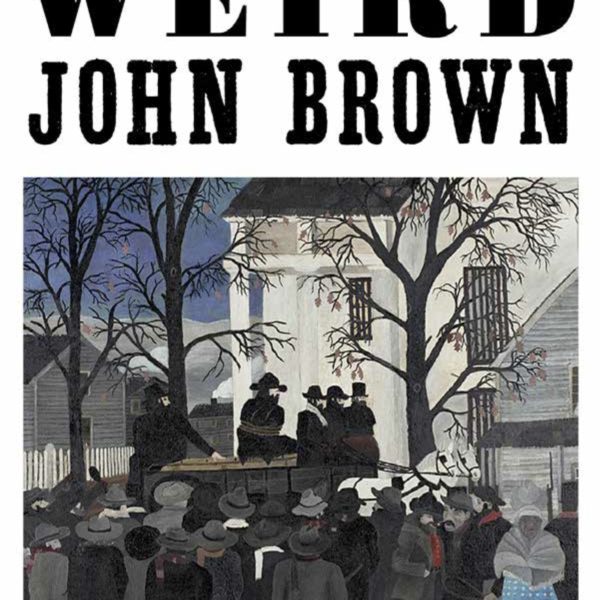

. . . In the book I think about what it would mean to see Brown as a “Great Criminal” who did wrong but can still be read as a sign of a divine violence that breaks the hold of the slave system on social imaginations and so makes possible not just new ways of seeing the world, but new ways of acting, new ways of connecting with others, and new ways of deliberating together.

Ted Smith delivers an unprecedented thesis about Brown’s violent assault on slaveholders as the human side of a “divine violence.” From beyond the limits of any earthly system of political justice and social ethics, this is a divine judgment against the validity of an entire system of political ethics. Addressed, for one, to American ethicists today — both those who teach and study in the university and those who voice their ethical judgments on street corners, in churches, and across the Sunday dinner table — Smith’s words, while gently spoken, deliver their own report of divine judgment.

A bishop recently said that 90% of the homilies he has ever heard can be boiled down to two words: “Try harder.” Of all the things that Ted Smith’s book does well, the most compelling for me is his attempt to critique the ethical confines to which reflection on politics and violence — along with so much else — is often limited.

In conjunction with the Marginalia (part of the LA Review of Books), Political Theology Today has organized a symposium on Ted Smith’s extraordinary new book Weird John Brown: Divine Violence and the Limits of Ethics. Over the coming two and a half weeks, we will host responses to the book from E. Brooks Holifield, William Cavanaugh, Peter Ochs, Keri Day, and Andrew Murphy, concluding with a response to the responses by author Ted Smith. Here is the first response, from E. Brooks Holifield of Emory University.