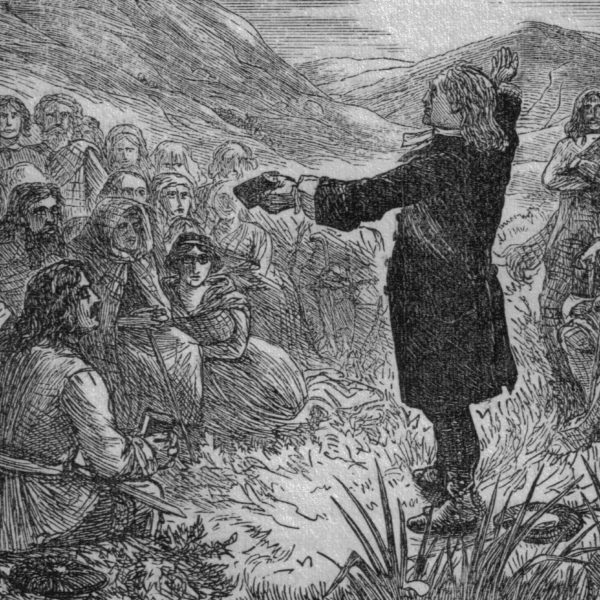

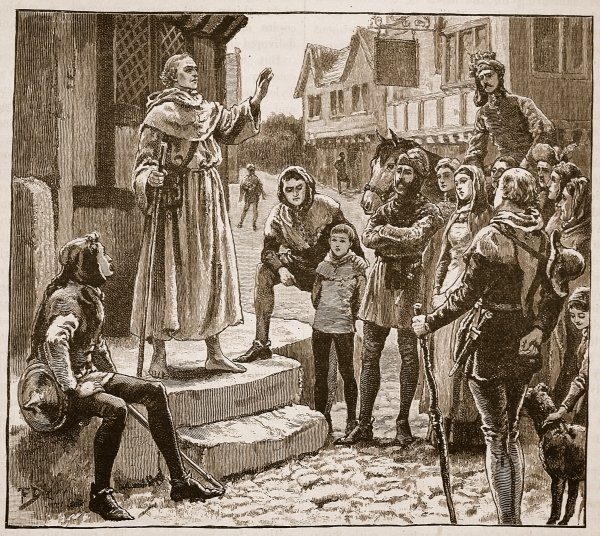

One Sunday around 1173, in Lyons, a wealthy financier named Waldo heard a traveling singer tell the story of St. Alexis, the son of a Roman senator who fled his family, became a beggar, and took to a life of prayer and service. Moved, he hurried to talk to a theologian, who told him of Jesus’ exhortation: if you wish to be perfect, go, sell what you have, and give it to the poor. And so he did.

There’s a fable I often heard growing up, about a Mennonite man (or Amish or Brethren, depending on where the story is being told) who was asked whether he was a Christian. His response: “Ask my neighbors.” The story encapsulates a certain historicist impulse in the Anabaptist tradition: the commitments we claim matter less than the commitments we embody. I first learned to care about the history of my community for just that reason. We learn who we are by considering honestly how we have lived.