One of the great paradoxes of John Calvin’s political theology can be captured in terms of two of the phrases the reformer used over and over throughout his writings. On the one hand, he emphasized, “the kingdom of Christ is spiritual.” On the other hand, through the kingdom of Christ God is bringing about the “restoration of the world.”

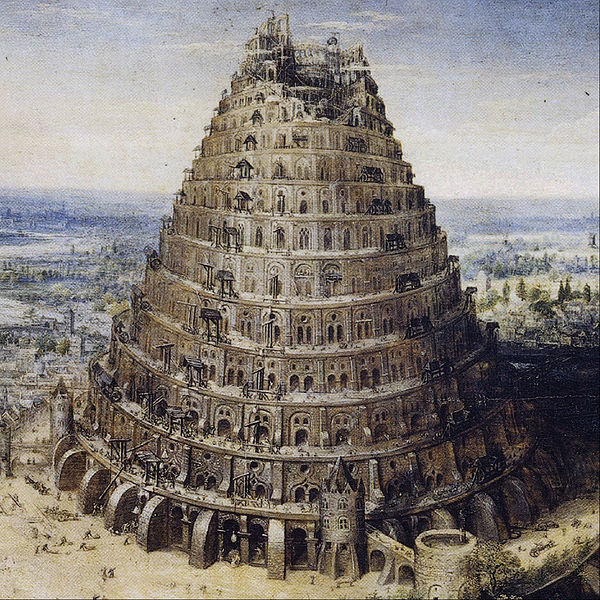

As the people of Pentecost, our political vocation is to manifest the reality of God’s worldwide kingdom, to be a place where the enmity between peoples is overcome and the many tongues of humanity freely unite in the worship of their Creator. Amidst the Babelic projects of the ages, the Church proclaims by its existence that the kingdom belongs to God, that there is no other true ruler over all the nations.

In light of the two kingdoms doctrine and the separation of church and state, understanding the appropriate form of Christian prayer for and engagement with the political realities of our societies can be complex. In Jeremiah’s message to an exiled people, we find a pattern for prayer in a pluralistic context, a calling that identifies our primary task to be one of seeking the common good and welfare of our communities, rather than one of submission or conversion.

We have spent now four posts tracing the historical development of Protestant two-kingdoms theology, and its influence on early modern political thought. This has all been an attempt to vindicate the claim, advanced in the first installment of this series, that the wider world of political theology has good reason to attend to the disputes over this doctrine that have heretofore been the province only of a characteristically combative subgroup of the American Reformed. Has it been vindicated?

In the 17th century, although the evangelical theme of the two kingdoms is everywhere. It is often somewhat hidden, though operant, behind other more forefront matters of contest–self-interest vs sociality as the basis of society, the divine or human grounds of legitimate rule, the relation of the State to nascent civil society, public and private–and sometimes the thing itself goes under aliases. It sometimes plays a greater role in the thought of the doctrinally idiosyncratic, for instance Hobbes, than it does in that of those otherwise more orthodox, such as Richard Baxter. This is a very vast and complicated field. Given that this is to be such a short overview, we will consider here merely one aspect of Lutheran two-kingdoms doctrine, that of the denial of political power to the clergy, and point to a few landmark instances…

Few figures in the history of theology can boast as contested a legacy as Richard Hooker, the purported forefather of a protean via media that is redefined with dizzying frequency. Until recently, many readings of Hooker suffered from the insularity that characterized much of Anglican historiography, doggedly committed to the assumption that England had its own history, blissfully independent from goings-on on the Continent. So when historian Torrance Kirby suggested that in fact, Richard Hooker should be read as a theologian of the magisterial Reformation, he touched a raw nerve among Hooker scholars, generating a hostile backlash that, after two decades, shows no sign of letting up. Perhaps tellingly, none of the responses to Kirby and his followers has bothered to engage the thesis at the heart of his re-interpretation, that Hooker’s theological response to Puritanism rested throughout on his Protestant—indeed, Lutheran—two-kingdoms doctrine…

Unlike some other second-generation Reformers, we do not have to read between the lines to find a two-kingdoms doctrine in Calvin. On the contrary, he is far less ambiguous even than Luther in setting it out at the center of his theology, inviting the question of why Calvin studies have until recently largely ignored the theme. The doctrine appears in the all-important chapter III.19 of the Institutes, as Calvin concludes his discussion of justification and prepares to transition to his massive Bk. IV, entitled “The External Means or Aids By Which God Invites Us Into the Society of Christ and Holds Us Therein.” Inasmuch as Calvin scholarship has attended at all to his two-kingdoms idea, it has frequently assumed, as VanDrunen does, that in delineating the “two kingdoms,” Calvin intends to delineate the two distinct institutions within this sphere of external means—church and state. However, from a structural standpoint, it is more compelling to see his distinction of the two in III.19 as a center-post, with the “spiritual government” pointing back to his discussion of the inward reception of the grace of Christ in Book III, and the “temporal government” pointing forward to his discussion of the external means in Bk. IV—on this basis, both the visibly-organized church and the state would constitute external means in the temporal kingdom. Certainly Calvin’s word choice in describing the two seems to bear out such a reading…