With conservative and evangelical ethicists falling dramatically off the anti-gay-marriage bandwagon at a remarkable pace, superstar theologian David Bentley Hart’s essay “Is, Ought, and Nature’s Laws” last month in First Things came like a spark on a dry pile of tinder. Challenging the optimism of many contemporary Catholic thinkers (and recently many evangelical thinkers as well) that natural law arguments can provide a convincing, broadly-appealing basis for opposition to gay marriage legislation, Hart provoked a tide of responses and counter-responses in the blogosphere, which continues even now. For at stake in Hart’s remarks were not merely how conservatives should and shouldn’t engage in gay marriage debates, but the nature of the public square and of natural law itself, the foundation upon which so much Christian political theory has been built over the centuries.

Rather than attempting to weigh in with yet another contribution to the wide-ranging debate, I will merely seek to provide here something of an annotated catalogue of the more significant blasts and counter-blasts

In this column, I want to engage in what Reynolds Price once referred to as “a serious way of wondering” about Exodus 20: 15-18—i.e., the moment at which the Israelites experience the divine self-revelation at the foot of Mount Sinai. Normally, this passage is understood as a theophanic event. To the extent that it involves the constitution of a nation or polity, it has usually been understood as a theocracy. Its intellectual expression (insofar as it addresses the issue of covenantal authority grounded in divine self-revelation) would therefore take the form of a political theology. To the extent that we read the above passage in this way, we have already rendered a decision—the essential significance of the passage would lie in the divine self-revelation. The fear which the Israelites experienced would amount simply and solely to a fear of God. Conversely, an acceptance of the commandments would amount to an acceptance of the political theology undergirding the theocracy.

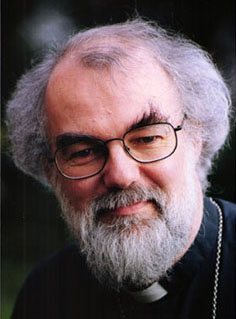

Sometimes it makes sense to concentrate on a single concept in order to understand the contribution of an individual to the history of ideas. This may mean artificially reducing the complexity of a person’s thought and vision. It may, however, be helpful in finding a hermeneutic ‘entry door’ into those thoughts and visions.

I have come to the (preliminary) conclusion that “Decentering” is such a key concept in the writing of Rowan Williams. “Decentering” features in Williams’ work both on questions of individual spirituality and matters of collective well-being. In Williams’ approach the individual and collective dimensions are not to be viewed separately but together. Individual choices bear upon the order of state and society and collective decisions provide the framework for the welfare of individuals and their ‘pursuit of happiness’.

The Israelites no longer needed God to provide manna for nourishment, but had their own land. The manna, in one sense, represents charity work. It is helpful and gives immediate attention to the person in need. Yet, if we are not advocating for the Promise Land where housing is affordable, jobs are of plenty, oppression is repressed, etc, then we need to have a reality check.

In a recent piece about Les Misérables, which is in general a fine study of the dynamics of law and grace in the film, Michael W. Hannon worries that a view of the state, and the political realm more broadly, as an unnatural institution is insufficient for a vibrant and vigorous engagement of this realm, or as he puts it “our faith in law.” Hannon aptly notes that Valjean, one for whom “it seemed as though he had for a soul the book of the natural law,” is the ideal in Hugo’s work. Valjean’s remarkable conversion, for instance, results in a situation in which he recognizes a greater sense of moral obligation rather than less.