In his When War Is Unjust: Being Honest in Just-War Thinking, theologian John Howard Yoder asks, “Can the criteria function in such a way that in a particular case a specified cause, or a specified means, or a specified strategy or tactical move could be excluded? Can the response ever be ‘no’?” (Orbis 1996, p. 3) In my judgment, the present crisis in Syria is indeed a particular case where a just war response is “no.”

Being a pacifist and an American is virtually impossible. Typically, the peace and justice community focus on violence issues, human trafficking, and other visible forms of oppression. They come out against war and unsanctioned military engagement (which is basically the status quo in the global capitalist empire: instead of war, we have police action). All of these things are unjust and need to be opposed, but ultimately they are the blood dripping from wound that we keep wiping up without recognizing their source: global capitalism.

Medieval religious houses were more than enclosed communities of men or women who spent their lives in prayer and worship, striving for their own salvation and interceding for the salvation of humankind. Clearly this was part of the story – it was not for nothing that the medieval historian Orderic Vitalis called monasteries ‘citadels of the Lord’, or that monks were commonly regarded as spiritual soldiers fighting against the power of the Devil and his cohorts.

I don’t know precisely when I first met Jean Elshtain. I think it was in the summer of 1995, in Swift Hall, home of the University of Chicago Divinity School. I must have been told of her arrival by one of the faculty. I know I talked to her in the corridor, that most important of places to ambush your teachers, and decided after that chat, that I would sit in on her class that Fall term—entitled, as I remember it, “Beginnings.”

n the matter of U.S. support for Israel, religion and politics operate as Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee, reinforcing each other in a slapstick display of tomfoolery. Although presidents have for decades lodged verbal objections to settlement expansion in the Palestinian territories, the Congress continues to authorize 3.2 billion dollars per year for Israel while Christian Zionist organizations send tax-exempt millions directly to the settlements.

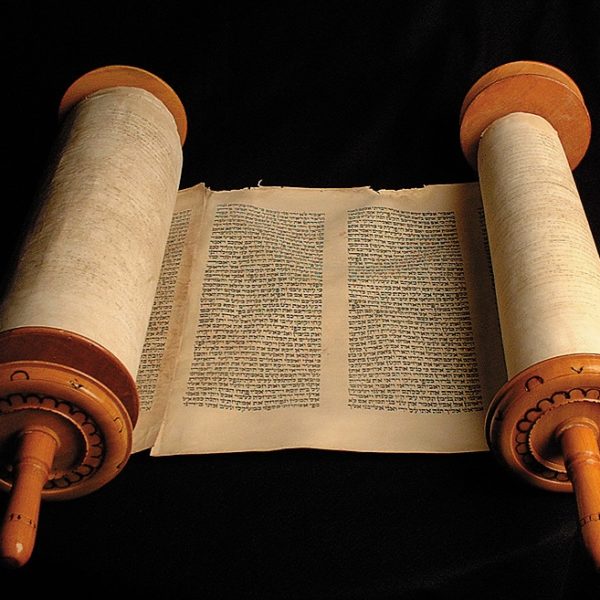

The prophet Isaiah was a city dweller, but his mind was on the countryside. Trees, vineyards, and fields populate his thinking and that of his successors in this long book, where vegetation serves both as metaphor (as in Isaiah 5:1-7), and as the life-sustaining growth on which humans literally depend (as in vv. 8-10). Agricultural imagery appears from one end of the book to the other (1:8; 66:17), spelling out both judgment and hope.

Can a people, after having duly consented to the formation of its government, remove that government using procedures not authorized by law? To put the question differently: can the formal legitimacy that a people provides a government preclude that people from exercising its sovereign power to strip those holding formal legitimacy of power, even though those in power have not violated the express terms of their compact with the people? These are the paradoxical questions that are at the heart of the political crisis in Egypt where duly elected president, exercising powers pursuant to a duly enacted constitution, was overthrown by the “people” who acted outside the formal rules “the people” had enacted for removing or otherwise disciplining its president.

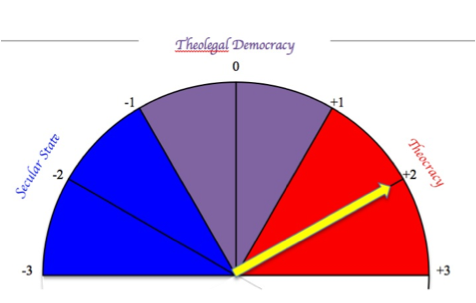

The United States is comprised of a religiously diverse citizenry, which leaves officials to balance the tension upheld by a constitution that simultaneously prevents the establishment of a national creed and yet preserves one’s right to freedom of religion. In practice, officials in the United States cannot legislate theology, but they can, and do, use theology to legislate.

As a result, the United States is not a secular democracy where laws guarantee freedom from religion and dismiss theological rhetoric in the political process; neither is it a theocracy, where a single religion prescribes all laws. Whether we like it or not the United States is a theolegal democracy.