As a White interpreter who has been examining the phenomenon of whiteness in biblical interpretation, both popular and academic, for nearly a decade now, I want to know just what whiteness looks like.

Because whiteness lies at the center of biblical studies, the accepted way of doing biblical scholarship is one that engages white questions, white concerns. The system forces scholars of color, especially those who receive their doctoral trainings in the western educational system, to be familiar with white scholarship.

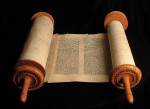

The descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob cried out for deliverance, and Yahweh heard them (Exodus 2:23). Notice carefully: Yahweh did not offer to comfort the Hebrews. Yahweh did not tell them to endure their situation because things would all work out in the end, or because after death they would be “in a better place.” Instead, Yahweh acted on covenant promises made with their ancestors by entering history.

Humans have grown exponentially in our propensity and power to conquer the earth itself. Despite being newcomers relative to neighboring species, humans usually behave as if we owned the place. But Psalm 95 speaks clearly: When we come into God’s presence—and there is no place God is more vividly present to us than in creation’s midst—the psalm says to come with thanksgiving, the polar opposite of greed.

We are the heirs of Elijah’s legacy. His influence is evident within later writings of the Bible, the Bible’s earliest commentators, and within the Bible-shaped parts of our own culture. But how might we assess our inheritance? Elijah is a hero of the covenant. Moses redivivus. A witness to God’s justice and mercy for those without power. And yet. . . Elijah’s legacy is also that of a “troubler” (1Kings 18:17-18). Although the prophet denied the title, the Jewish rabbinic tradition has not been afraid to name troubling features of his ministry. He seems more pre-occupied with his own difficulties than those of the people. He does not advocate for the Israelites. He uses violence.