The telos of border imperialism as described by Walia and served by policies like the Priority Enforcement program is manifestly blasphemous on any number of levels. The most obvious, and the most commonly identified by theologians is that it denies the presence of Christ in the persons of exploited, oppressed, colonized, and working people.

On 13 August, the main floor of the New Haven People’s Center was characteristically hot and unusually crowded for a late summer evening. About half a dozen lawyers, nonprofit workers, and labor union staff were there for a meeting of the Connecticut Immigrant Rights Alliance.

The last week of March 2015 saw a downturn in reproductive and sexual justice in the U.S. The Indiana General Assembly approved the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, allowing businesses to discriminate against LGBT people and to opt out of providing health insurance for abortions.

He faces no criminal charges. Indeed, a U.S. judge ordered him released five years ago. Nevertheless, Mohamedou Ould Slahi remains in Guantánamo Bay, after more than thirteen years in captivity. He was snatched out of his home country of Mauritania shortly after 9/11/2001, and then renditioned to Jordan, Afghanistan, and finally Cuba. In U.S. custody he has endured beatings, threats, sexual assaults, sensory deprivation, lengthy exposure to cold temperatures, food deprivation, deprivation of medical care, stress positions, and forced nudity.

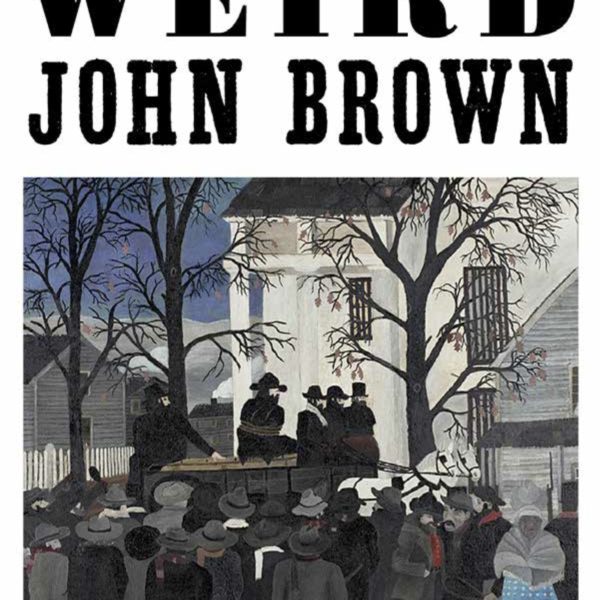

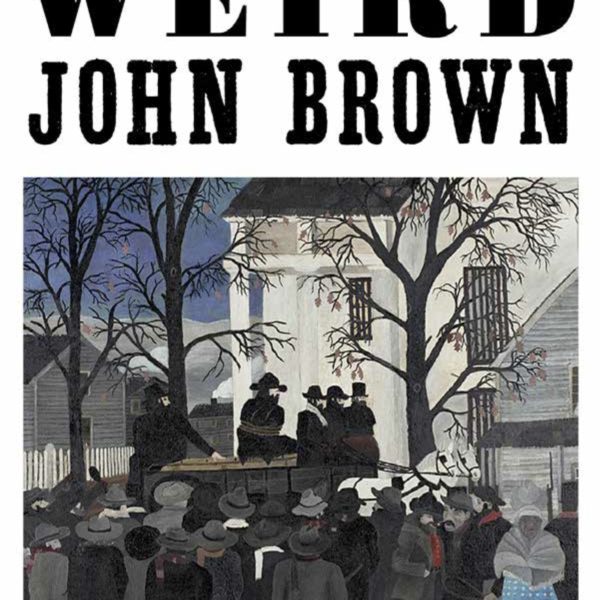

. . . In the book I think about what it would mean to see Brown as a “Great Criminal” who did wrong but can still be read as a sign of a divine violence that breaks the hold of the slave system on social imaginations and so makes possible not just new ways of seeing the world, but new ways of acting, new ways of connecting with others, and new ways of deliberating together.

I think that a politics of penitence and repair can disrupt old divisive racial patterns, potentially enabling the emergence of new racial communities not marked by old forms of racial hatred and violence. Smith’s argument for penitence and repair is compelling and I do think that a Christian political theology calls upon us to consider these two important practices. Smith presents a theological discussion of pardon that eventually takes us to repentance and repair when addressing racial wounds.

For the past two weeks I have made my annual pilgrimage with university students to Vienna, which because of the strong United Nations presence and the hundreds of NGOs specializing in international humanitarian services and outreach is often known as the “gateway city” for globalization.

We always end the course with a two-hour train ride west of the city along the Danube to the Denkstätte (“memorial”) that is the Mauthausen Concentration Camp, an originally preserved site of the monstrous brutality and anti-human obscenities inflicted on a vast diversity of different peoples now at least 70 years ago by the Third Reich.

At the very least we might say that both nonviolence and pacifism should attempt to understand and redirect violence. And maybe we should shelve the tired terms for a spell and speak of life-giving or death-dealing acts, which might reframe exhausting debates about property destruction. Pacifism should not be at odds with physical force, with the force of physicality such as sit-ins, strikes, human chains, roadblocks, or even strategic property destruction.

Nonviolence and pacifism are often pitted against one another, even though pacifism was once considered the activist term to distinguish it from nonresistance. Now, pacifism is thrown under the bus, even by vigorous advocates of nonviolence. For instance, Gene Sharp clarifies that nonviolent action is, appropriately, action that is nonviolent, as opposed to pacifism.

In 2008, I worked in Ramallah as a journalist and interim editor for the Palestine Monitor, a web-based news source committed to “exposing life under occupation.” I traveled throughout the West Bank, writing several articles about the village of Ni’lin, whose olive groves and roads are fractured due to the construction of the separation wall.

Being a pacifist and an American is virtually impossible. Typically, the peace and justice community focus on violence issues, human trafficking, and other visible forms of oppression. They come out against war and unsanctioned military engagement (which is basically the status quo in the global capitalist empire: instead of war, we have police action). All of these things are unjust and need to be opposed, but ultimately they are the blood dripping from wound that we keep wiping up without recognizing their source: global capitalism.