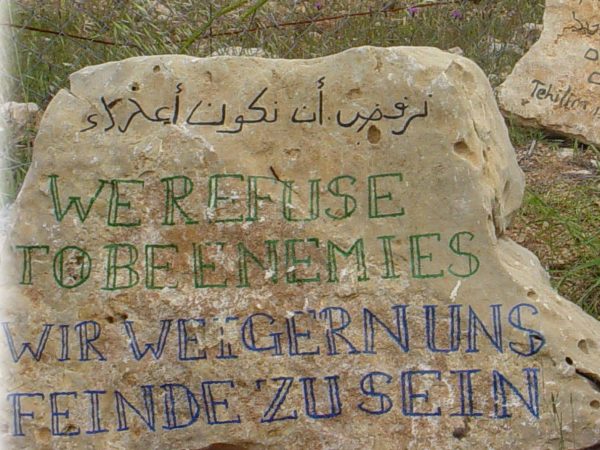

The virtues and practices include confronting the issue rather than the person, practicing forgiveness, tolerance, and reconciliation, embracing the enemy as a child of God, and protecting human dignity and the common good. It explores how the combination of CST and nonviolence can address human actions that sustain marginalization, racism, conflicts, oppression, domination, and diverse forms of social exclusion.

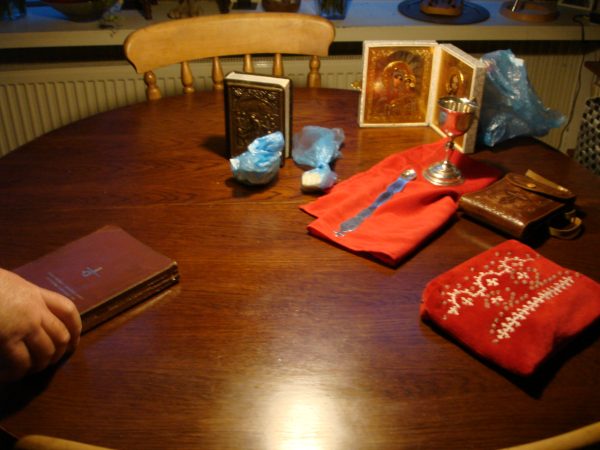

In turning away from more abstract debates about liturgy to those that center on its lived and material dimensions, we hope to enliven a conversation about ‘lived liturgy’ to consider what practices uphold, challenge, or fail to account for the global political order.

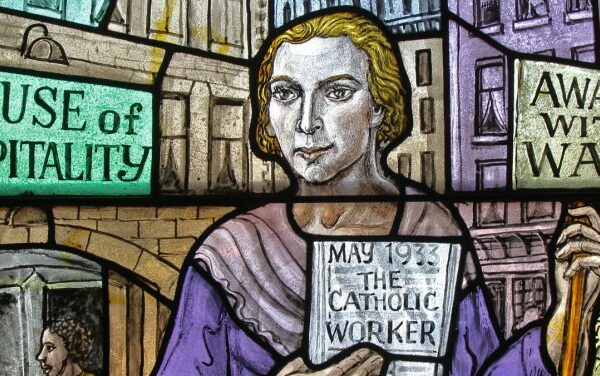

[P]romoting justice and defending human dignity need not only hinge on grand self-sacrificial gestures…. That social structures are sustained by social practices suggests that the everyday is consequential too and dispels the notion that smaller or more mundane acts are too paltry and thus powerless to effect the kind of structural change justice requires.

Jean-Luc Marion waded into political discourse with his 2017 book Brève apologie pour un moment catholique (Brief Apology for a Catholic Moment) which uses aspects of his phenomenological and theological project to argue for a model of non-political politics: one based exclusively on the perfect will of the Triune God.

An examination of responses that are counteracting the fascism emboldened by Trumpism; including Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker movement as well as Christ’s moral imperative for anti-fascist action. A provision of counternarratives of hope to the prevailing motif of the Catholic Right’s resurgence.